The Tennessee school board banned Maus “because of its unnecessary use of profanity and nudity and its depiction of violence and suicide.”

NEW YORK—One of the first books I read when I first moved to New York was Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. Miller was on the shit list of the Catholic poohbahs in Manila and to read him was to commit, in their quaint language, a mortal sin and thus risk being doomed to the eternal fires of Hell. Unless one immediately sought absolution via the confessional.

First published in Paris, Tropic was initially banned in the US but finally deemed non-obscene by the US Supreme Court in 1964.

The clerics lost the battle for my soul. Henry, my oldest brother, and Beatriz, his wife, then living in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan and now both deceased, had Miller’s books. I read, no, devoured, Tropic, and went on to read his other works.

Also on that list were James Joyce’s Ulysses and D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

We happened to have had a copy of the Joyce book at home. Riffing through the pages, I came across the 18th episode, the final one, where, unable to sleep, the unfaithful Molly Bloom remembers vividly her sexual escapades, in Joyce’s pioneering stream-of-consciousness style—marked by the regular appearance of “yes” that both begins the episode and ends it, and the book as well. As for DH, well, he would have to wait until New York.

It was also in this city by the Hudson that I first read Jose Rizal’s incendiary late 19th-century novels, Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo. Even though Rizal is the country’s national hero, his works then were still considered too radical in their withering critique of not just Spanish colonialism but also and in particular the Catholic Church that stood squarely behind the imperial throne. The sad irony was that his novels were not part of my alma mater Ateneo de Manila University’s curriculum in the 1960s—and he was its most storied alumnus.

The strictures on what literature we wished to read and films to view were meant to shield us impressionable teenagers from the innumerable temptations flesh is heir to. To set us on the straight and narrow path all the way to eternal glory: that was intent of the good fathers. However, banning an object often makes it utterly irresistible. (Had God kept quiet about that tree, we might now all be cavorting in the Garden.) If a film were deemed salacious, immoral, and offensive, that was enough for us to sneak into movie theatres and watch that which was verboten. Not that we had to sneak in but that was the feeling we had, the antennae of our conscience ever on the alert for the moral police.

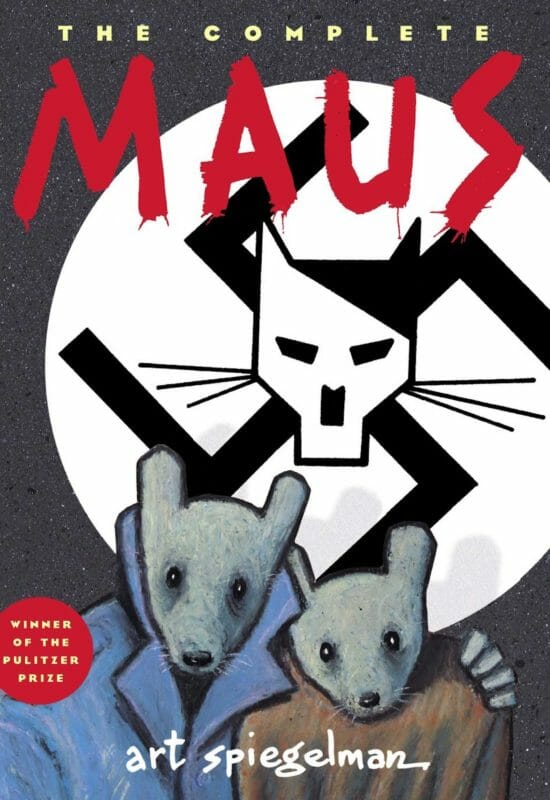

I remember these ”guilty” pleasures because of the current attempts to once again ban books, notable among them Maus, the Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel by Art Spiegelman about the Holocaust, among whose survivors were Spiegelman’s parents. The Tennessee school board behind the ban stated that it did so “because of its unnecessary use of profanity and nudity and its depiction of violence and suicide.”

Planet Earth to Tennessee: Hello! The Holocaust was all about violence in all its inhumane forms, from genocide and sexual violations to torture and suicides due to unremitting despair. To expect polite language in such dire circumstances is to expect hyenas to sing “Amazing Grace.”

Interestingly, when Schindler’s List was released in Manila, the chief censor at that time wanted to ban the film even though he hadn’t seen Spielberg’s film. The reason? Nudity. One would think the nudity being referenced was of the erotic, soft-core variety, rather than an accurate portrayal of conditions in the death camp where women were routinely sexual game.

Maus isn’t the only target of such benighted folks. According to the American Library Association, Harper Lee’s classic To Kill a Mockingbird is on its Top 10 Most Challenged Books “for racial slurs and their negative effect on students, featuring a ‘white savior’ character, and its perception of the Black experience.” Included as well are John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, and Nobel laureate Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye.

What such ban-the-books enthusiasts are really after is not education but indoctrination. The mindset is one of fear, the fear not only that their offspring will come to think independently, and break free of received wisdom, but also of a perhaps more profound fear of what they have long suppressed, believing that within themselves lies a Pandora’s Box that must lie forever unopened.

Theirs are lives begging to be examined but alas likely will not.

Copyright L.H. Francia 2022