Filipino teacher follows dream on an island in the Bering Sea

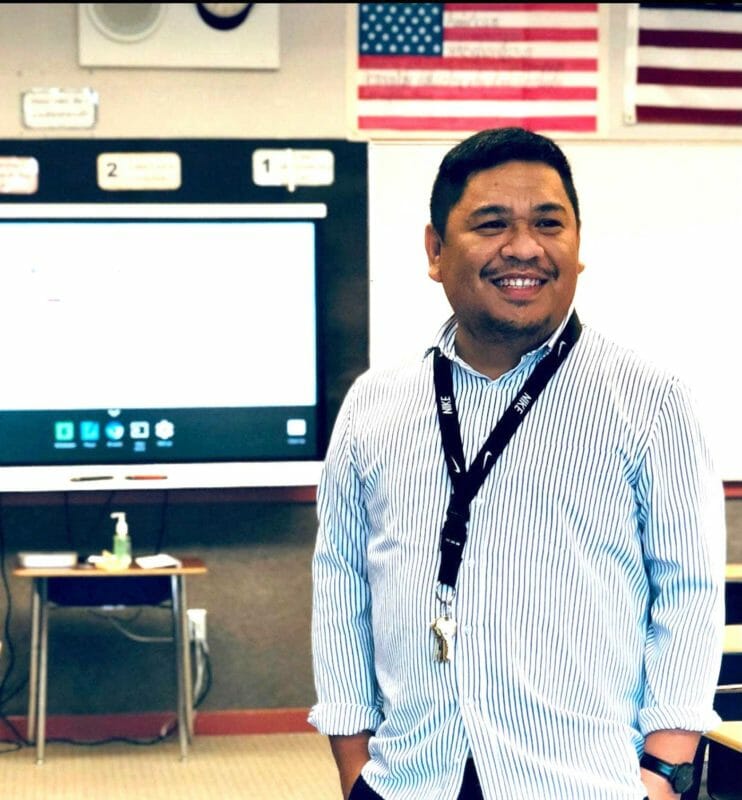

Originally from Cotabato City, Jayson Guerrero is currently teaching high school mathematics in Gambell, St. Lawrence Island, Alaska. CONTRIBUTED

If one ever needed proof of how Filipinos commit to opportunities when they come knocking on their door, Jayson Guerrero, 33, is it. Guerrero, a Cotabato City native, had already proved that even before he started his first day of teaching in a small village named Gambell, Alaska.

The American village is located on St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Strait of Alaska. Guerrero’s flight to his teaching assignment in August 2018 was a grueling 14 hours from Manila to LA, followed by a five-hour layover in LAX before departing on a six-hour flight to Anchorage. From Anchorage, he took a 90-minute flight to Nome where he caught his final 45-minute plane ride to his destination, Gambell.

Growing up, Guerrero set his sights on becoming a teacher. His pedagogy is building genuine relationshipswith his pupils. Hearing his students’ daily struggles makes him understand them more. This approach makes his class easier to manage. He wants to learn from his students too and believes that creating an environment where teaching and learning become part of the same experience is the best way for studentsand teachers to understand one another, especially regarding background and culture.

Jayson Guerrero (right) has two Filipino roommates, also his teaching colleagues, who have become a major support system. CONTRIBUTED

Before coming to the U.S., Guerrero worked in the realm of policy and governance for a non-government organization that works closely with the Philippines’ Department of Education. The opportunity to teach abroad was suggested by his friend, who had already spent a year in the U.S.as a teacher. There is a great need for teachers for various overlooked U.S. school districts.

For Filipinos, the initial allure of teaching in the U.S. is, of course, a higher salary that generally can’t be matched back in the Philippines. For example, a one-month salary of a public school teacher in Alaska is comparable to an annual salary teaching in the Philippines.

Aside from the financial benefits of working overseas, Guerrero believes that teaching in the U.S. can help him develop personally and professionally. He strives to learn new and different teaching techniques and strategies from these experiences.

Also, as an avid traveler and adventure-seeker, he plans on visiting all 50 states. For the past two summers on school break, he had gone on road trips with his friends, hoping to accomplish this goal. He has already visited 40 out of the 50 states. He wants to inspire others and demonstrate that dreams can come true. “I remember I was just dreaming about traveling on a road trip when I was still in Cotabato.”

The process

It took Guerrero about four months to complete all the required documentation before he was permitted to fly to the U.S. Sharing his experiences with fellow Filipinos regarding getting a U.S. teaching job, Guerrero says, “The first step is to find a school district hiring foreign teachers then complete an application online to secure a job offer from your chosen school district.”

The next step is to find a sponsoring visa agency and apply for a certificate of eligibility. After gathering these documents, you can apply for a US visa. He says that although the application process was rigorous, if you have all your documents ready, it makes everything easier.

He was granted the Exchange Visitor (J1) non-immigrant visa that allows an individual to participate in work-and-study-based exchange visitor programs. This visa grants him a maximum of five years of teaching in the US. After finishing this five-year visa, he can continue teaching if a school agrees to sponsor an H1B visa, which allows an individual with a “specialty occupation” to work in the United States for three years.

Life in Gambell, Alaska

Guerrero was part of a cultural student-exchange program sponsored by the U.S. State Department when he attended Northern Illinois University in 2010. Although he had lived in the U.S. prior to his current post, working and living in Gambell, Alaska only scratch the surface of his first-hand experience of America.

Gambell village has a population of approximately 800 people called the St. Lawrence Island Yup’ik. The Asiatic Eskimo group collectively called Yupiit are widely known for their carvings on walrus ivory and subsistence hunting of Bowhead whales.

The village has no coffee shops, no movie theaters, or malls to visit after school. There are not manyactivities to participate in and he admitted to spending a fair amount of free time watching movies and TV shows on his personal computer. He is also studying Spanish.

One of the biggest adjustments he has had to endure is the extreme cold of Alaska. Winter’s extended dark hours also took a substantial toll on his mental health. The village only averages 4-5 hours of daylight during winter. “It can be depressing when it feels as though it is always nighttime.”

Although living on a remote island can feel isolating at times, Guerrero is grateful that there are other Filipino teachers in the school and the district. He has two Filipino roommates, also his teaching colleagues, who have become a major support system.

Since the Yupiit rely on hunting and fishing, there is only one small native store on the island. Everything must be flown in, including groceries.

“When you are cut off from the road system, the prices of gas, groceries, and other important things increase significantly.” Even with an Amazon Prime account, it will still take about two to three weeks before the packages arrive on the island. The acquisition of necessities needs to be planned. There are only two flights a day, morning, and late afternoon from Anchorage to Nome. Then three flights a day from Nome to Gambell on a ten- seater plane via Bering Air.

Teaching in Alaska

According to US News’ “Best States” ranking in 2019, Alaska ranked 49th out of 50 in terms of education competitiveness despite high government funding and support before New Mexico. Guerrero teaches in a school that has a population of 230.

“For two straight years, among all the students who graduated high school, only one went to college. College is never a priority here. After graduation, most students enter the

minimum wage workforce or start their own families. Many of the families here live below the poverty-line.”

Guerrero instills in his students an appreciation for how lucky they are because of the generous resources provided by the U.S. government. Public school students in pre-K-12 typically get free breakfast and lunch every day. School supplies are also often subsidized. Most schools are also given good school equipment and facilities.

In Alaska alone, “the government spends an average of $17,000 per student in the state while the national average is only $12,000. That’s roughly Php 850,000 per student,” Guerrero shared.

As the US public school system continues to cope with cramped classrooms and a shortage of teachers, some school districts open their doors to foreign teachers, and Filipinos are always top choices. Guerrero is proud to be a Filipino teacher. He attributes Filipino educators’ edge to English being the second official language in the Philippines.

“Filipino teachers have always satisfied the state-mandated requirements to teach in the U.S. — academic degree, teaching experience, and teaching license. Filipinos have a high level of commitment.”

Guerrero is one of the pioneering Filipino teachers hired by his school district in 2018. He holds a BSE major Mathematics from Notre Dame University in Cotabato City and a Master of Arts in Education major inEducational Leadership and Management from De La Salle University, Manila.

Guerrero teaches Algebra, Geometry, and Precalculus with students ranging from 14 to 18 years old. He enjoys using games to engage students in his process of teaching math. His average class size is 10 to 12 students for each subject, and he holds five classes a day. He is required to clock in at the school by 8 a.m. He has an hour of preparation time before classes start at 9 a.m. He gets a 30-minute lunch break before resuming the school session, which ends at 3 p.m.

“I can say that the workload here is less stressful compared to the Philippines, where we need to be at school from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m.”

During the start of the pandemic Guerrero, like all of humanity, experienced anxiety, and depression. The internet connectivity is not reliable in the village, so online learning was ruled out. Most families do not own a computer at home anyway. So, their options were limited to the implementation of “distance-learning.”

As in the Philippines, they use the “modular model” of learning. Prepared packets are sent to students every week. It was a big adjustment for Guerrero; he was not familiar with this type of learning modality. It was a sharp learning-curve to say the least.

Being a Filipino educator

It is common knowledge that teachers in the Philippines are overworked, underpaid, and underappreciated. Guerrero shares that this reality hits particularly hard knowing that the average monthly teaching salary in the Philippines is Php 20,000 (US $400).

“I love my country [the Philippines] but I do believe that we need to empower ourselves before we can give back to the community. Save up and gain more experience and pursue graduate studies abroad then decide if you want to go back to the Philippines. We have our own way of giving back to the community.”

Guerrero sees himself retiring in the Philippines, but he is not closing any doors to the possibility of living permanently in the U.S. He knows that his goals may change over time, but he currently believes that beinga university professor when he goes back home would be a meaningful way of giving back and acknowledging his roots.

Recently, Guerrero has been able to invest in a property in his hometown Cotabato City from the hard-earned money he made from teaching in the U.S. He dreams of finishing a Ph.D. in one of the U.S. universities if an opportunity arises. Even if it is a difficult decision to leave the Philippines, Guerrero encourages his fellow Filipino educators to explore teaching in the U.S. while there is a demand in the workforce.

“Be prepared mentally, emotionally, financially and physically. Teaching in the U.S. is a whole different experience. Once you get hired, manage your finances well but also don’t forget to enjoy and spend on yourself. Take the opportunity to travel around the States.”