U.S. Army’s PH Scouts and the last cavalry charge in WWII

The Philippine Scouts became members of the regular United States Army on September 27, 1901. The scouts were no longer employees of the colonial insular government.

One of the least known historical events of World War II in the Philippines was the cavalry charge by the 26thPhilippine Scouts on January 16, 1942. At a time when airplanes, tanks, and heavy artillery were the weapons of choice, there was still an important role for the cavalry.

When the order was given to charge the approaching Imperial Japanese Army, without hesitation the scouts unholstered their pistols and galloped for the Japanese lines. This heroic cavalry action 80 years ago was officially the last cavalry charge in American military history.

The Philippine Scouts became members of the regular United States Army on September 27, 1901. The scouts were no longer employees of the colonial insular government. The predecessors to the Philippine Scouts were the Macabebe Scouts who had served the American military since 1899. A large percentage of the Macabebe Scouts were residents of Macabebe and Masantol in Pampanga Province. The stellar performance and loyalty by the Macabebe Scouts were the principal reasons why the Philippine Scouts became part of the regular U.S. Army.

The U.S. Army restricted the size of the scouts to twelve thousand soldiers. A recruit for the Philippine Scouts enlisted in the U.S. Army for three years. The scouts were designated as military and were completely separated from the Philippine Constabulary, which was a component of the police forces. There were times when the scouts assisted the constabulary. Initially, all the officers in the scouts were Americans. Since one Filipino was admitted each year to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, eventually there were Filipino officers in the Philippine Scouts.

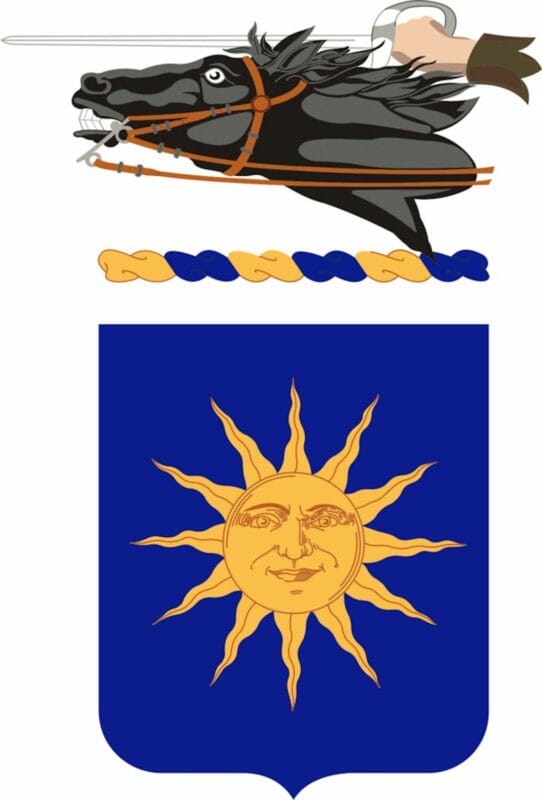

The 26th Philippine Scouts cavalry regiment’s insignia.

In official military documents, the Philippine Scouts were designated as PS. Like all enlistees in the U.S. Army, the scouts were selected for either Infantry, Artillery, Coast Artillery, or Cavalry. Although the traditional Cavalry was fast becoming obsolete, there was still glamor and prestige of being a soldier on horseback.

The U.S. Army was very proud of its colonial soldiers. During the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904 in St. Louis, Missouri, a contingent of Philippine Scouts was transported to the United States and placed on display. A substantial number of American attendees were intrigued with their newly formed scouts in American military uniforms.

Following the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands by the Japanese Imperial Navy, the Philippines were bombed only eight hours later. Most of the advanced aircraft at Clark Field and Nichols Field were destroyed. The combined American and Filipino forces attempted to repel the Japanese invasions at the beaches and mountain passes.

The 26th Philippine Scouts cavalry regiment played a significant defensive role during the Imperial Japanese invasion of Northern Luzon. Due to the landscape, natural barriers, and many topographical obstacles, it was easier for the mounted scouts to maneuver and fight in difficult terrain compared to vehicles, tanks, and artillery.

Once the American commanders ordered the retreat to the Bataan Peninsula, the Philippine Scouts 26th Cavalry aided the retreat of General Wainwright’s Northern Luzon Filipino and American forces. The actions by the 26th Philippine Scouts minimized the loses during the retreat to Bataan.

Once the combined troops arrived in Bataan, they established a defensive barrier called the Morong-Abucay Line. The Philippine Scouts including the 26th cavalry were part of the defensive line. In fact, the section of the line facing the strongest Japanese thrust was manned by the Philippine Scouts.

In early January 1942, the veteran Imperial Japanese Army attacked the defensive line on Bataan. The combined regular U.S. Army, Philippine Scouts, Philippine Commonwealth Army, and former Army Air Corp members gave up some territory but essentially held the line. Eventually, the Imperial Japanese Army conceded defeat. General Homma ordered a halt in the attacked and waited for resupply and reinforcements. His honored reputation in the Imperial Army was shattered. This was the first major defeat for the Japanese in World War II. The Filipinos and Americans had won round one on Bataan.

During this round one fighting on the Bataan Peninsula, a most unusual sight occurred near the Lady of Pilar Catholic Church in Morong. An elite cavalry platoon of the 26th Philippine Scouts were ordered on January 16, 1942 by Lieutenant Edwin Ramsey to mount up, grab their sidearms, and charge the approaching Japanese infantry soldiers. The scouts had practiced this mounted charge many times at Fort Stotsenberg in Pampanga Province.

The Imperial Japanese troops were surprised and overwhelmed by this cavalry charge. Many of the Japanese infantry soldiers made a hasty retreat. The cavalry platoon eventually dismounted from their horses and fired on the enemy. Lieutenant Ramsey was wounded during the action. The Philippine Scouts cavalry had proven their worth. This mounted charge has been designated as the last cavalry charge in American military history.

Eventually in early April 1942, the starving and sick Filipino and American soldiers and scouts surrendered to the Imperial Japanese Army. Lieutenant Ramsey and some of his Philippine Scouts decided not to become prisoners of war. They escaped to the mountains and organized guerrilla units to oppose Japanese occupation.

Dennis Edward Flake is the author of three books on Philippine-American history. He is Public Historian and a seasonal park ranger in interpretation for the National Park Service at the Eisenhower National Historic Site in Gettysburg, PA. He can be contacted at: flakedennis@gmail.com