Journalists honored on 125th death anniversary of fellow journalist Rizal

Journalist and Consul General Elmer Cato (left), Pulitzer Prize Winner photojournalist Cheryl Diaz Meyer and host Dr. Romulo Aromin Jr. INQUIRER/Carol Tanjutco

NEW YORK — The Knights of Rizal New York Chapter and the Philippine Consulate General of New York honored Filipino journalists on the Philippine national hero Dr. Jose P. Rizal’s 125th year of martyrdom, noting that Rizal himself was a journalist of the reformist expatriate publication La Solidaridad.

The Dec. 10 program at The Players NYC featured the stunning works of Pulitzer Prize winning photo journalist Cheryl Diaz Meyer, as well as the recollections of former journalist and current Consul General Elmer Cato during the conflicts in Libya and Baghdad.

The program was led by KOR-NY Mariano Aquino Jr., Dr. Romulo Aromin Jr., Rogelio Penaverde and Aprille Aquino, in cooperation with NY-based nonprofit Eagle Eye Charities Inc. whose president, Dr. Aromin, emceed.

Filipino American photojournalist Cheryl Diaz Meyer, Pulitzer Prize Winner of 2004 Breaking News Photography, recalled covering the front lines of Iraq and Afghanistan war on terror: “I felt like I detonated a bomb when I told my mom I am going to Afghanistan to cover the war.”

Diaz-Meyer was a volunteer for Dallas Morning News in 2001 during the first conflict to be covered by digital satellite phone. There was no hotel, no facilities for washing and she had to procure sleeping bags from fellow journalists. Her recollection of Taliban women and young girls who never attended school left an indelible mark in her mind.

“When I returned to Dallas, I was such an angry person” after six weeks of enduring war and molestation by men. Not long after, she went back to the frontlines, invited by the Marines of the 2nd Tank Battalion. Some 600 journalists were invited to go to Iraq.

At the time, there were no female Marines on the front lines; she was the only woman embedded with 1,000 men. It was not until 2013 that women Marines where allowed on the front lines. She rode in amphibious assault vehicle.

There were no convenience facilities; the only way she could do her personal routine was with a shovel and a poncho within the view of thousands of men.. She was soon referred to as the poncho queen.

“The war became personal to me. I just wanted it to stop. The Marines made it stop,” Diaz Meyer recalled. She transmitted pictures of violent attacks, with corpses, to the horror of military women who berated her for publishing the images.

Some of these pictures appeared in New York Times war section and made their way to Donald Rumsfeld’s desk. She was removed from embed, but then she had already joined another group in Baghdad. There, she met women who were thrilled to see another woman on the frontline.

At the end of her story, Diaz Meyer asked, “What really did we accomplish with the war on terror? The war is neither black nor white, we are all losers in the game of war. Some of the Marines I was with are dead, while some were left with a permanent damage to their psyche for having fought and endured such violence.”

She left Dallas News and decided to stay home to raise her only daughter while struggling with postpartum depression mixed with PTSD. For the first time, she was learning who she was, as a wife, and as a mother.

Photographer Cheryl Diaz Meyer transmits images via satellite phone after the U.S. Marines’ Second Tank Battalion moved north from Kuwait into the southern Iraqi city of Basra March 20, 2003. CONTRIBUTED

Fast forward to 2019, she received grants to document “Comfort Women,” Filipino women and young girls systematically enslaved and raped in military brothels during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines 76 years ago.

Since its inception in 1917, the Pulitzer Prize have been given to only five Filipinos, the first one was in 1948. Diaz Meyer’s works have been recognized by the Overseas Press Club, Visa Pour l’Image, the NPPA, the White House News Photographers Association, and many others throughout her 25-year career.

Elmer G. Cato, KCR, current Philippine Consul General of New York and a career diplomat, was formerly a journalist. He began at 16 years old as a cub reporter for Pahayagang Malaya, before becoming a correspondent for Manila Chronicle, Reuters, Kyodo News, Philippine News and the Saudi Gazette. He was national editor for the Philippine Daily Globe and Today, executive editor of the Angeles Sun and K Magazine in Pampanga.

Cato was serving at the Philippine Embassy in Washington DC in 2015 when he volunteered to go to Iraq to head the Embassy in Baghdad. Five days after he arrived, an ISIS suicide car bomber blew himself up at the hotel where he was staying.

After serving three years in Iraq, he again volunteered to serve in another conflict zone, Libya, where he headed the Embassy in Tripoli for two years. He said he felt compelled to go to both conflict zones because somebody had to look after hundreds of OFWs working in both countries. He shared photos of Iraq and Libya that most people have not seen — picturesque images of sights and people bereft of any signs of the death and violence that the two countries have been associated with.

Former journalist and current diplomat Elmer Cato standing guard at the Philippine Embassy in Tripoli, Libya, which he led in 2019. CONTRIBUTED

Asked by Diaz Meyer about his job assisting distressed nationals, he replied: “The third pillar of Philippine foreign policy is to assist Filipinos in distress abroad. Part of that job requires us to repatriate Filipinos from danger zones but only if they want to.”

In Baghdad, then Charge d’Affaires en pied Elmer Cato captured images of the deadly suicide bombing of the five-star Babylon Warwick Hotel where he was billeted. ISIS was at its peak when he arrived in Iraq and part of his responsibility was to prepare for a possible attack on the Embassy, which was located in the dangerous Red Zone district of the Iraqi capital. He drew up plans to protect embassy personnel and at the same time defend the chancery in case it was attacked.

Cato’s five other colleagues from the Department of Foreign Affairs not to be captured, taken hostage and displayed by ISIS before decapitation. He said, “We all agreed to take our own lives, reserving the last round of the pistols issued to us and shoot ourselves in the head.”

In Libya, embassy employees braved rocket and artillery barrages to look after Filipinos there when civil war broke out in 2019. This was complicated by the outbreak of the pandemic, but embassy personnel rose to the challenge and extricated more than 300 Filipinos to safety.

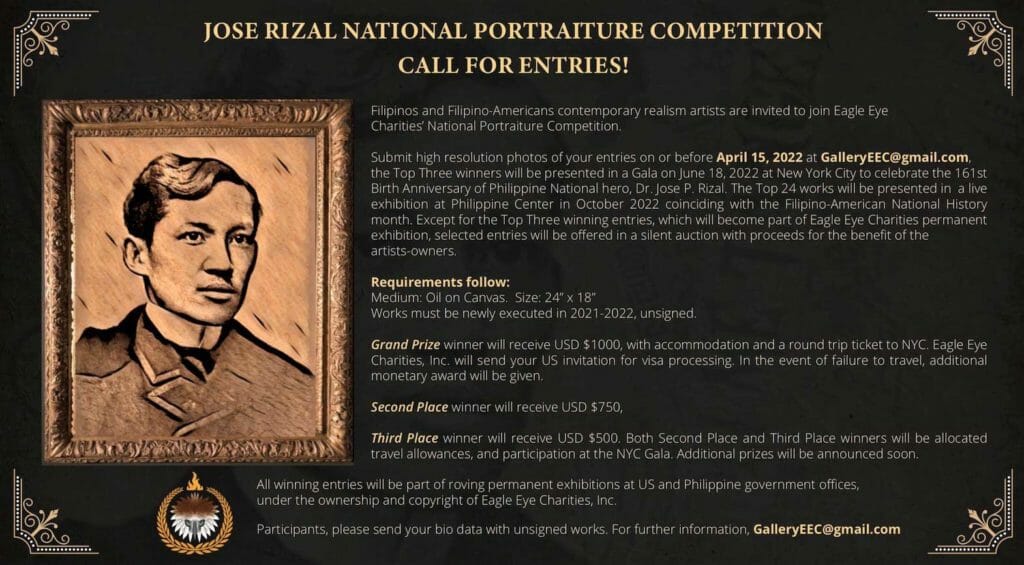

To conclude the commemoration, New York-based nonprofit Eagle Eye Charities Inc. announced a Jose Rizal National Portraiture Competition, open to all Filipinos and Filipino-American contemporary artists around the globe. Round-trip air tickets to New York, hotel accommodations and cash awards of $1,000, $750 and $500 await the Top Three winners. Participants are requested to email their artist profile or bio to confirm their participation to GalleryEEC@gmail.com Deadline for submission of entries is April 15, 2022. Call for entries and qualifications are published at the website: EagleCharities.org