Stateside Pampanga native renews love for his language

Masayang ka-Paskuan ampon Masaplalang Bayung Banwa!

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year!

For Rey Maniago and his wife, Donna, both retirees, nothing is merrier than to hear the greetings in their native language, Kapampangan.

After 11 years, this is only the third time they will be celebrating Christmas in Pampanga.

“First was in 1974, before joining the Navy, then 2006 with one of our kids, and this year,” Rey says.

With feasts of tugak batute (frog sausage), tamales, kamaru (cricket), talbos at bulaklak ng kalabasa, sitaw and a lot more, Christmas is more fun in Pampanga. But Pampanga is more than just cuisine.

Speaking its language adds to the joy of the Maniagos’ homecoming. Unfortunately, Kapampangan is included on the endangered language list in the Philippines. The younger generation of Pampangueños hardly speak or understand their language due to proximity to Manila, and also immigration.

This fact prompted Rey to focus his advocacy on reviving his native language, even in America.

Joining the Navy

A native of Mexico, Pampanga, Rey joined the US Navy after graduating from Holy Angel University (formerly Holy Angel College) in Angeles City with a degree in political science. While waiting for a job, he managed his brother’s art gallery in Angeles City, which was frequented by Americans. Clark Airfield was in Pampanga while the US Naval Base was in Zambales.

“At the time, without any prospective job opportunities, joining the US Navy was a chance to earn a living, not to mention see other places,” Rey explains.

Qualified Filipinos were recruited into the US Air Force and Navy while thousands worked as civilian staff until these bases finally closed down on December 27, 1992.

In December 1975, while his family in Pampanga was celebrating Christmas, Rey was in a boot camp in San Diego, USA.

“My first Christmas was rather bleak to say the least. That was the first time I experienced the dreaded and real homesickness,” Rey recalls.

Eventually, Rey married Donna, his high school friend, and flew back to the US. After a year, he was stationed in Japan and finally transferred to New Orleans. After his retirement, the Maniagos settled in Long Beach, California.

‘Re-discovering’ Kapampangan

Despite speaking Kapampangan at home, Rey did not speak it to his children.

“When the boys were growing up, I didn’t have any awareness of the fact that children can absorb languages in their formative years,” Rey explains.

Rey believed that his kids would be confused if he spoke to them in Kapampangan. Fortunately, his mother was then living with his family, so his eldest son picked up some Kapampangan from her, enough for him to get by when talking to relatives in Pampanga.

Not wanting to repeat his mistake, Rey and Donna are speaking to their grandkids in Kapampangan.

Back in the late ‘80s, when Rey was vacationing in the Philippines, he noticed a shift in the Kapampangan language in Pampanga. Some people (obviously Kapampangans from their accent) spoke to each other (and parents to their young children) in Tagalog. This sparked Rey’s language advocacy.

In 2000, Rey joined the Yahoo group ANASI (Academya ning Amanung Sisuan, International). The members exchanged their opinions about the dying culture of Pampanga, especially the language. This made him think how he could contribute to its preservation despite living in the States.

Birth of Tegalugan

When Rey discovered Facebook and You Tube, he started to utilize these to promote his advocacy.

Michael Raymon Pangilinan, author of Kulitan (Kulitan is the Kapampangan writing system) and noted Kapampangan advocate based in Pampanga, is one of those who inspired Rey.

Pangilinan has written extensively about Kapampangan language and culture for decades. He suggested that it would be useful to have videos discussing Kapampangan. It was the birth of Tegalugan.

Literally meaning tinagalog (rendered in Tagalog), Tegalugan is Kapampangan mixed with words borrowed from Tagalog. This is how the majority of Kapampangans speak nowadays. Pangilinan says that the Philippine policy on the use of only English and Filipino as mediums of instruction in schools had been a factor in the “death of languages.”

Pangilinan explains better internet access is a factor in promoting an advocacy, like Rey’s Tegalugan series of videos on YouTube (https://youtu.be/jDhJCiNR-5Y; https://www.facebook.com/groups/kapampangan.capampangan/). Cultural advocates based abroad also have access to archives not available in the Philippines and most importantly they have time and resources to run their advocacies.

Engaging the youth

Rey explains that it is not easy to gauge the youth’s interest in keeping the language alive if it is based on only a particular province like Pampanga. Yet, he was disappointed to hear young people speaking in Tagalog even though it isn’t their native language.

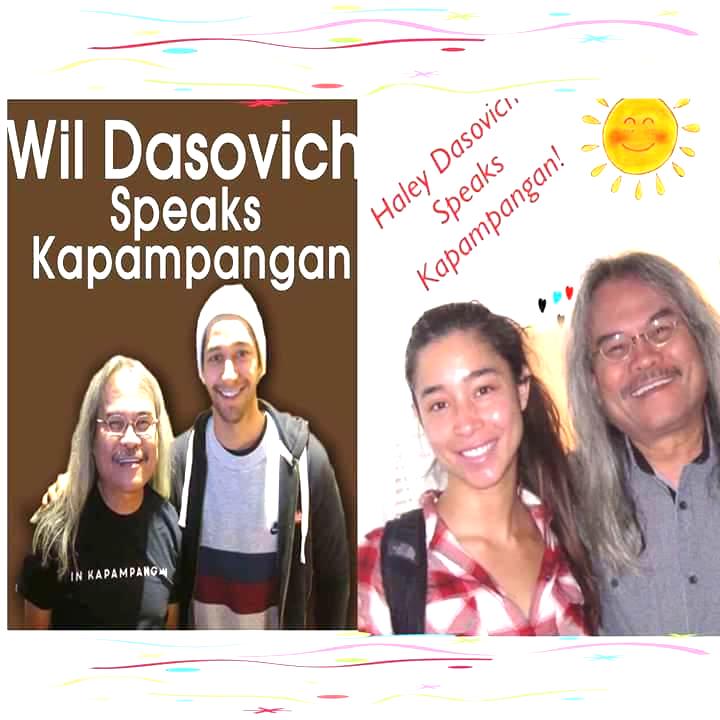

To reach more viewers, especially the young generations in Pampanga and the US, Rey asked the help of famous vloggers, siblings Wil and Haley Dasovich, whose mother is a Kapampangan.

“I see mostly positive responses to my videos on social media, especially my latest videos where I utilized the help of famous sibling vloggers, Wil and Haley Dasovich, which have garnered the most views so far,” Rey says.

While many Kapampangan homes in the US have traditional Noche Buena and parol (Christmas lantern), Rey believes that speaking the native language must not be like Filipino food that one just misses and only cooks during festive seasons.

Rey believes that it is not yet too late to teach second-generation immigrants their parents and ancestors’ native language.

“Indigenous language is a major part of their identity. It helps a lot when they go back to the Philippines so they can express themselves in their native languages.”

Paskung Mayap ning Dispu, Rey greets everyone in traditional Kapampangan.