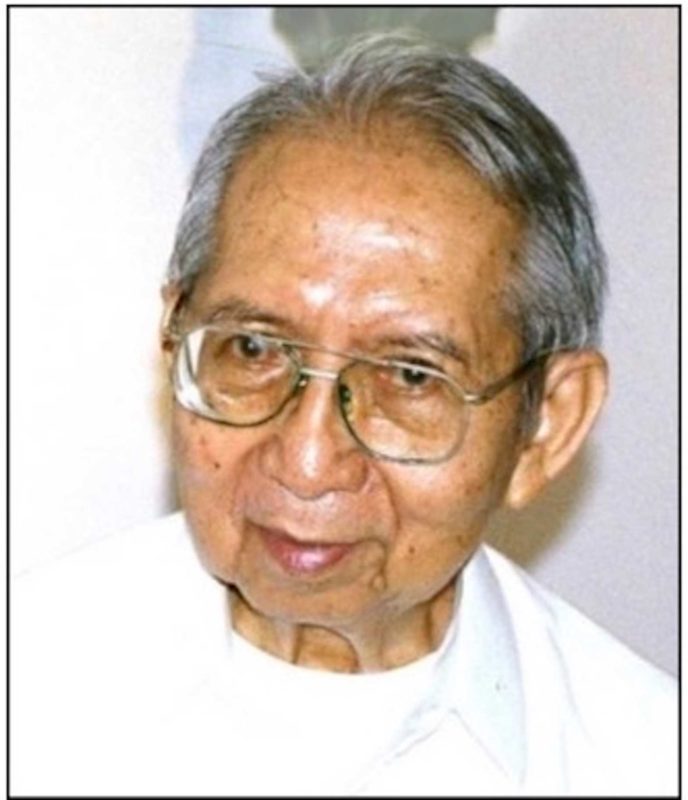

Roque Ferriols, SJ, 1924-2021

NEW YORK—We called him Roque, not to his face and never disrespectfully, whenever we’d discuss his philosophy courses and pedagogical style. Our humanities group—there were about seven of us—studied with him. He was after all chair of the humanities department, the humanities being regarded by many (including my parents), as a field of study with no practical value. Hence, few chose it as their major, probably one reason why it initially appealed to my inner snob. When it became readily apparent that Roque was a brilliant professor, and that our small cohort had him all to ourselves, we felt privileged, a cut above the rest of our undergraduate peers.

That brilliant mind ceased to be in the early morning hours of August 15, a Roman Catholic holy day marking the Assumption of the Virgin Mary and one day shy of his 97th birthday. In its brief statement, Ateneo de Manila University’s Office of Alumni Relations described Roque as “[O]ne of Ateneo de Manila’s cultural icons who has left an indelible mark on the lives of generations of Ateneans,” and who “taught Philosophy for over 40 years, established the university’s AB Philosophy degree program, and pioneered the teaching of Philosophy in Filipino. Among his published books are Magpakatao: Ilang Babasahing Pilosopiko (1979), Pambungad sa Metapisika (1991), and Pilosopiya ng Relihiyon (2014).”

When I emailed the sad news to a few good friends and cograduates, none of whom had had him as a professor, one wondered whether he had been “a terror in the classroom.” “Terror” was how we described professors who behaved as autocrats towards their students. I replied that Roque was strict but fair, someone who didn’t suffer fools gladly. He could spot a dissembler and dilettante a mile away.

We were on our best behavior not out of fear but out of respect, for the arc of his knowledge and scholarship was breath-taking. He broadened our intellectual horizons, with material that not only encompassed Western civ’s rock star philosophers, from the pre-Socratics and Plato, to Immanuel Kant, Kierkegaard, Heidegger, Husserl, Sartre, Gabriel Marcel, and even Teilhard de Chardin, but also Eastern thought, though to a lesser degree. Thus were we introduced to the Bhagavad Gita.

Taking his classes made me see clearly why I had chosen humanities as my major. Studying the humanities in retrospect was really a process of knowing how to ask the right question, more elemental than seeking answers. Answers simply generate more questions. The question then arose: is there an endpoint, an Ultimate Answer that answered and absorbed all questions?

Or, conversely, is there an Ultimate Question, one that points to an infinite sea not of troubles but of possible answers?

If all this sounds like an exercise in reflective thinking, it is, and modeled on what would have been, when I was still immured within the university’s ivory tower, a standard assignment from Roque. He had, it seemed to me, that same intense, wall-eyed and piercing gaze as Jean-Paul Sartre. It felt as though Sartre was his doppelgänger, though Roque was by no means a nihilist.

He was a catalyst in a profound way, a teacher who was genuinely interested in what, or more precisely how, each one of us thought, the manner in which each of us perceived the world, ourselves in that world, and underlying all of that, what it meant to inhabit one’s own skin, to be human—warts and all.

Roque’s pedagogical approach was new; he had us write papers, or thought pieces, where one’s own thinking was not only encouraged, but demanded. This was a revelation and, as far as I was concerned, a revolution. A brilliant, highly regarded professor interested in my thinking? That just blew me away.

In essence, what Roque was asking us to do was to essay into one’s being, to help us understand ourselves, to wander into uncharted waters, heeding Socrates’s dictum, that the unexamined life is not worth living. While it was only normal to hope my essays would earn an appreciative nod of his head, along with his trademark “Ah yez!” I also knew that that would come only if I were true to myself.

I did have brilliant teachers in English literature, such as the late Rolando Tinio and Bienvenido Lumbera. They were exceptions to the rule, of faculty who for the most part relied on rote learning. Competent, yes, but uninspiring. You gave back what was given to you, nothing more, nothing less. What all that rote learning meant was that later on you had to unlearn what you learned, or thought you did.

Under the keen eye of Roque, we examined, as one course title had it, the History of Ideas. This seemed to fit the zeitgeist of the times, even as “they were a-changin’,” as Bob Dylan put it. Why were they a-changin’? The Sixties was a time when the young were, in the countercultural slogan of the day, urged to tune in, turn on, and drop out, when rock ‘n’ roll as a cultural force was irresistible. Globally, young folks like ourselves were eager to make love, not war. Rejecting the staid lifestyles of the previous generation, they (and we) were adherents and practitioners of the sexual revolution.

Sometimes in class, Roque would go on anti-American diatribes, leaving us curious as to the cause. But having lived now in New York for several decades, I have some understanding of what he must have experienced as a young person of color pursuing studies for the priesthood in New York. And yet one of his best friends among the resident American Jesuits was a tough New Yorker with the build of a linebacker who once remarked that for relaxation Roque would read Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologica.

Under his guidance, the study of the humanities opened up intellectual vistas, as well as a burgeoning awareness of my being as a person and quite possibly a writer. The insight that he passed on to us, the one I most cherish and still contemplate, is that each of us is at one and the same time completely unique and completely the same as every other person. I have never found a more comprehensive and pithy summation, at once simple and profound, of our being in the world.

Thank you always, Roque. Copyright L.H. Francia 2021