One Californian’s ‘pag-ibig’ for the Philippines

When one learns in the news about the recent vandalism of the Saint Junípero Serra and Indian boy statue across the street from Mission San Fernando Rey de España outside Los Angeles and the ongoing battle between government forces and militants affiliated with ISIL in Marawi, Philippines, it makes one wonder what connects the human family.

Though separated by the Pacific Ocean, a bond of love, or pag-ibig in Filipino, between California and the Philippines does exist. It is a deep relationship, rooted in Catholic history. Though I am no expert in the history of the Philippines, I am passionate about it by default. Many of my Pinoy friends in California have said that I am an honorary Filipino, having married a Filipina (Iris née Carillo Llavanes). Since we are both school teachers, we have had the luxury of spending about a month every other year with our son in the Philippines during our summer vacations. We recently made our third trip there as a family.

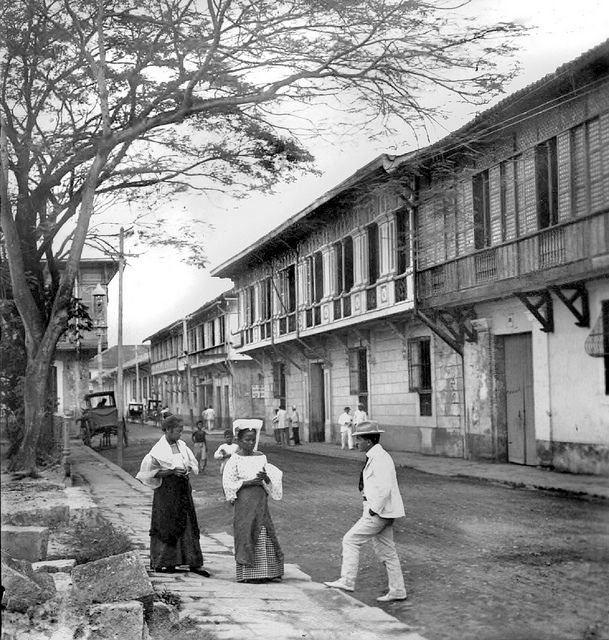

Actually, my connection to the archipelago goes back even before my nuptials. A relative of my dad’s died there on August 27, 1945 and is buried at the Manila American Cemetery; my dad served in the U.S. Navy at Subic in the early 1950s; my brother and his Marine unit came from Okinawa on a humanitarian mission after the Mount Pinatubo explosion in 1991. So not only did I fall in love with a Filipina, but also with the history of her native country. What I have been able to see more clearly every time that I visit is the story early Catholic history in California, where I was born and we reside, parallels that of the history of Catholicism in the Philippines. When I visit places like Daraga Church in Albay and learn its history, I see so many similarities with the Church’s history in the American West. When I read books and visit museums that deal with Philippine history, I am amazed by the connections between the story of my home and my wife’s homeland. Both histories include saints, sinners, galleons, tragedy and triumph.

The Philippines and what is now the American state of California was once part of a much larger enterprise, the Spanish Empire. Galleons plied the seas bringing riches from the Philippines to Mexico and eventually to Spain. Spanish and Filipino sailors on galleons landed on the shores of California as early as 1587. The late David J. Weber, professor of history at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, shed light on the vastness of the Spanish Catholic empire in the Americas in a lecture series that he gave in 2003-2004 at Baylor University. It helps one understand just how vast the enterprise was.

Between 1493 and 1824, 200,000 missionaries toiled in the Americas. By the late 1700s, 1/2 of Spain’s claim in the Americas (29 times the size of Spain) was controlled by independent Indians. Surely native tribes of the Philippines also controlled the majority of the archipelago. The history of the Catholic Church in California, however, began much later than in Mexico and the Philippines. In short, early Philippine history has much more to do with early Mexican history, but for those in the three locales under Spanish authority, all roads led to Mexico City, the capital of New Spain.

The Spanish claim to California, then referred to as Nueva California, was theoretical. Fearing intrusion by the British and Russian empires, the Spanish sent missionaries and troops to colonize their claim. California would not be subjected by conquest or pacification, but by the Sacred Expedition. On July 1, 1769, Junípero Serra (1713-1784), the Mallorcan-born Franciscan priest, brought Catholic Christianity to the present-day state of California. He entered San Diego and 15 days later would found a mission, San Diego de Alcalá, the first of nine consecrated during his tenure as father president of the missions. Like many of his predecessors, his single-purpose was to bring the gospel to the gentile. He was both an administrator and a catechist, like a hybrid of Fray Domingo de Salazar (1512-1594), the first bishop of the Philippines, and Saint Pedro Calungsod (1654-1672), the young Catechist martyred in Guam.

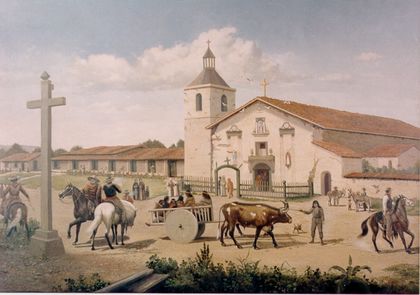

Just like when Magellan and Legazpi arrived in the Philippines over two centuries before, Serra and his military escort, consisting of 238 men, 78 being soldiers, were met by diverse societies. The tasks were similar in both places though, to introduce a new religion and government to the native people. Unlike the Philippines where the pueblo, or town, was the norm, Serra was adamant that his venture not include pueblos and its encomiendas—grants by the Spanish Crown to colonists conferring the right to demand tribute and forced labor from the local inhabitants. Instead, missions were set up to Christianize the natives. Once baptized, they also gained Spanish citizenship. Serra, however, would argue off and on with government authorities for the rest of his life about who was in charge of the care of the Catholic natives. Serra argued that they remain at the missions under the guidance of the priests. He knew from history that the track record of how natives were treated in pueblos was poor. By 1790, just over two decades after Serra founded the first mission at San Diego, 11 missions and four presidios, or forts, had been constructed, with an estimated 30 priests and 211 soldiers.

The Spanish missions in California died a slow death after Mexico successfully revolted against Spain. According to records at The Early California Population Project, Serra’s legacy included 101,000 baptisms, 28,000 marriages and 71,000 burials at all twenty-one missions and from the Los Angeles Plaza Church and the Santa Barbara Presidio. When the first Bishop of Alta (previously called Nueva) California, Francisco Garcia Diego y Moreno, arrived at Santa Barbara on January 11, 1842, there were only seventeen Franciscan priests, mostly aged and infirm, to minister to the people at the twenty-one secularized Indian missions and six Spanish pueblos (the first, San José de Guadalupe, was founded November 29, 1777—known today as the city of San José, the hub of Silicon Valley). The Mexican era in California lasted for a short time, from 1821-1848.

The cultural interaction came at a cost, though. Like the many revolts against colonialism in the Philippines, California had some too. But most deaths came from diseases that the California Missions Indians had no immunity to. Historians put the pre-contact native population in California at between 225,000 and 300,000, and estimate that they declined by 33% by the end of the Spanish and Mexican eras. After California became part of the United States in 1850, actions supported by the government fit our modern definition of genocide (as adopted by the United Nations in 1948). By 1870, the number of Native Californians was 30,000. Jonathan Cordero, a sociologist at California Lutheran University, estimates that by 1900, there were about 800 mission Indians.

So, when I visited Fort Santiago in Intramuros, Manila, I thought of Castillo de San Joaquin in San Francisco. When I read about the Magalat Revolt in 1596, it reminded me of the 1775 revolt at Mission San Diego. When I walked through the Casa Gomez at Villa Escudero in Quezon province, I recalled my visit to Casa de Estudillo at Old Town San Diego State Historic Park. When I saw pilgrims in prayer at Regina RICA, a Marian shrine in Rizal province, I was mindful of those who do so at the California missions. However, where I experience malalim na pagkakaibigan, or deep friendship, the most, at home and in my adopted country, is at Holy Mass. Though an ocean separates California and the Philippines, we are closer than one may think. We are bound by the Faith.

Christian Clifford is the author of three books about Catholic Church history in Spanish-Mexican California. For more information, visit www.Missions1769.com.