Life With Father: A doctor-war hero in the ’50s

Dr. Jesus F. Hidalgo and wife, Soledad Dato, in 1970s. CONTRIBUTED

TORONTO—Her father’s name—Dr. Jesus F. Hidalgo—appears in the U.S. Congress war records for serving the American soldiers and guerillas before and during liberation from the Japanese invasion.

But Dr. Telly Hidalgo-How would not have known of her father’s exploits during the Second World War had she not read an account by a relative, Ambassador Simeon D. Hidalgo, who wrote an article for Dr. Hidalgo’s 100th birth anniversary souvenir program in 2005.

Ambassador Hidalgo, the Philippines’ first envoy to Cuba, said his godfather and uncle joined the guerilla unit Blue Eagle in Pasacao, as head of its medical detachment. His prompt diagnosis and medical treatment of Major Russell Barrows, chief of the intelligence unit of AFWESPAC in Camarines Sur, when the latter fell gravely ill, saved the military officer’s life. “The liberation of Camarines Sur would have taken a different course if Major Barrows’s sickness had not been correctly diagnosed.”

Years later, on a visit to the Library of Congress, Ambassador Hidalgo found his uncle’s name among those cited in the U.S. War Records of the Second World War.

As part of the medical corps, Dr. Hidalgo had to care for the wounded that would take him deep into the forests. He even had to go into hiding from Japanese militia as he was on the Wanted List, having been elected in the city council in 1939. When Municipal Council of Naga City was reorganized in 1945, through the initiative of the Philippine Civil Affairs Unit of the 8th United States Army, Dr. Hidalgo again served as councilor from May 1945 to March 1946.

A graduate of the UP College of Medicine Class of 1931, Dr. Hidalgo would have been one of the pensionados sent to the U.S. for training. However, he chose to stay and serve his community in Naga City. He became president of the Camarines Sur/Bicol Medical Society, and practiced for 55 years.

Dr. Hidalgo-How says it was a 24/7 practice interrupted only by her father’s customary siesta, tennis, and sleep.

“Even then, patients would interrupt her father’s sleep or even while watching the occasional movie where a note would appear on the telon (screen): ‘Dr Hidalgo, emergency.’ It seems there were no emergency rooms in Naga during the ’50s. Lines were long with patients running to a hundred daily, more during epidemics.

The young Dr. Hidalgo seated on steps second from left, with Camarines Sur Medical Society. CONTRIBUTED

“On Fridays there were also long lines of alabados, when the doctor would offer alms of coins. He charged patients about P1 or less, even none per consultation, with free samples thrown in. No charge when a patient died after a long illness. He would even offer to drive them to a funeral home in lieu of ambulance service. Also, free room for those coming from outlying barrios.”

That was how it was in the early days of medical practice, recounts Dr. Hidalgo-How, as she reminisced the days of her parents, Dr. Jesus “Isong” Hidalgo and Soledad “Choleng” Dato.

Isong completed high school at Camarines Sur High School where he graduated valedictorian before he took his medical course at the University of the Philippines. Choleng went to the Colegio de Sta Isabel where she graduated valedictorian in 1934. They were married in 1931 and had twelve children, three of whom died.

Although Dr. Hidalgo-How has scant memories about the relationship between her father and her seven brothers, she believes they must have found time to go out hunting for wild birds and deer: “It was Father’s sport aside from tennis. It was a complicated family life, raising all these men, dealing with growing-up issues.”

What she could just surmise, however, was that she got most of the attention.

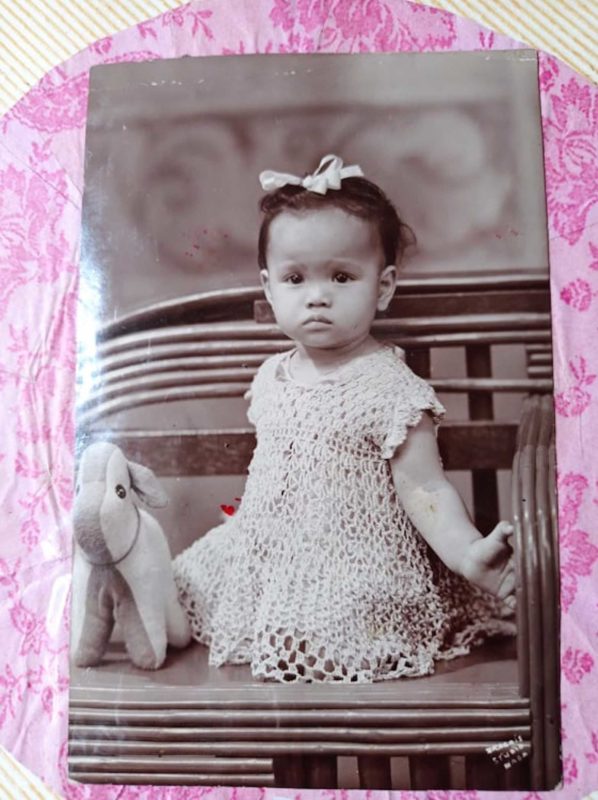

Early photo: Dr. Telly Hidalgo-How as a baby. In October 2020, Dr. Cleotilde “Telly” Hidalgo-How was included in The Asian Scientist’s 100 List of most outstanding researchers, which acknowledges the success of the region’s best and brightest. Dr. Hidalgo-How of University of the Philippines-Manila was chosen for her work in the understanding, management, and diagnosis of tuberculosis among children and adolescents.

“Every kind of extracurricular work I found a lot of encouragement. Father even encouraged me to learn touch-typing myself, probably to be better than Mother (a magazine columnist) who wrote her articles with just two fingers. Mother got me to learn piano early by getting one for me and older brother Jerry. I had my formal classical training. I did quite well in school—even in dance, writing, math and ended up valedictorian.” She won an American Field Service scholarship and spent a year in Michigan.

Dr. Hidalgo-How says she learned personal simplicity from her father.

“He came from humble parents who were so hard-working, especially his Inay who used to sell zacate to feed horses. Carretelas (horse-drawn carriages) were still the means of transport before the turn of the century.” Her Lola Tani would also make and sell vinegar in big vats, kept in a room.

“They lived on the riverside of Balintawak, so Inay raised geese and ducks. They also had farms that they could reach by boat. From their hard work, they left big tracts of farmland.”

When the young Dr. Hidalgo-How became of age, her parents never made an issue about suitors.

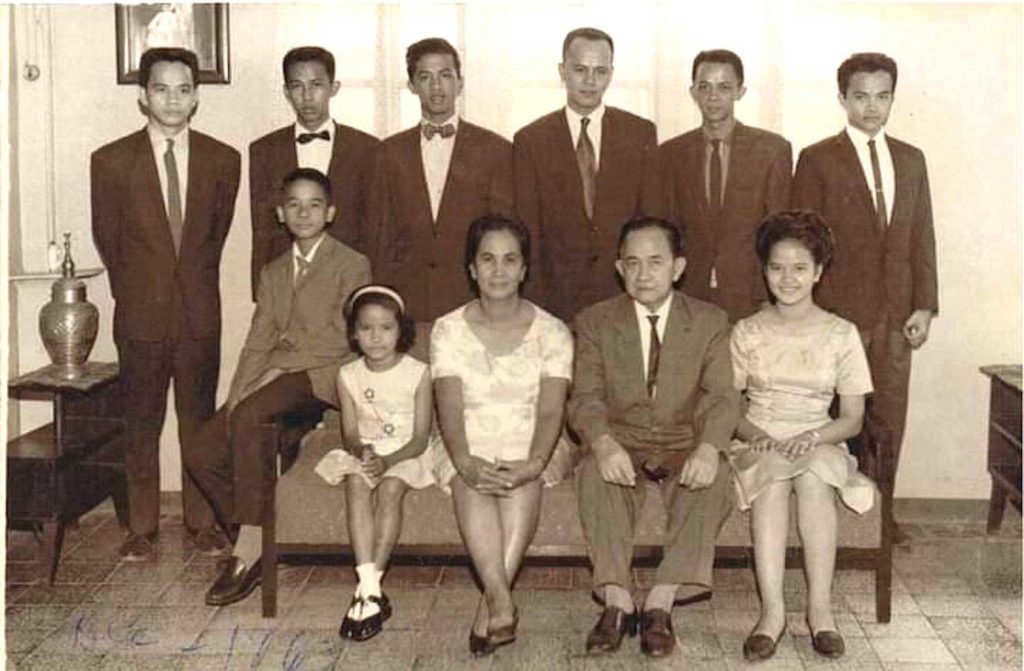

The Dato-Hidalgo family. Standing from left: Jerry, Manuel, Mirardo, Ruben, Julian, Jaime. Seated on arm: Jesus Jr. Seated: Amelia, Soledad, Jesus Sr., Cleotilde/Telly. CONTRIBUTED

“It was more about my brothers who found entertainment in harassing some. I knew my father was looking after me even with his busy schedule.”

When she attended parties, her father would be waiting in his car to fetch her. “Probably that kept me set on my studies, so I would not cause them anxiety. When I met my first boyfriend and future husband, Francis How, I was near spinsterhood (by Mama’s generation’s standards)—it was after pre-med, just before I entered medical school.”

Her stoic attitude, a trait that Dr. Hidalgo-How carried throughout, she also picked up from her father: “He was like his Inay, a hardy woman whom my mother called the Empress Dowager,” she says with a laugh.

Among her memories was when she once eavesdropped at her parent’s room. “Father said, ‘Telly is so used to being praised, getting a good word from everyone. She should know how to face defeat or a crisis.’ So I kept that in mind, and stayed alert and well-grounded. Perhaps that’s how I was able to cope with my breast cancer in 2002, and when, while I was undergoing chemotherapy, my husband was diagnosed with Stage IV lung cancer.”