Long road to togetherness for GI fathers and their Amerasian kids

David Parscale, Mae, and Brenda during a visit in Missouri in February 2015. CONTRIBUTED

Shira Victoria Sato has only a picture of her biological parents. She did not even know her father’s name, only her mother’s, Marivic Leyson/Layson. She knew that they met in Clark Airbase in the Philippines. It is the only link to her past.

Shira’s adoptive mother took care of the pregnant Marivic on condition that the baby would be given to her. After Shira’s birth on July 14,1987, Marivic left and was never heard from again. Shira’s adoptive mother worked overseas, so she was left to the care of relatives.

Mae Somoray didn’t know her father either. Unlike Shira, she was raised by her loving mother and grandmother. Mae’s mother, Annie, was a domestic worker inside the Officer’s Housing in Subic Naval Base. Mae’s mother died when she was five.

Shira Victoria Sato then and today. CONTRIBUTED

Mae was in grade school when Mount Pinatubo erupted in June 1991. Their home was destroyed.

“We had no electricity, TV, fridge, game console, etc. Radio is life! Which is why I became a radio DJ, I guess,” Mae shares.

Mae was able to finish Accountancy through the support of the Pearl S. Buck Foundation and a scholarship from the City of Olongapo.

Shira and Mae are among the estimated quarter of a million Amerasians in the Philippines. Many of them live in poverty and suffer discrimination and stigma. They are hoping that one day, their fathers would find them and bring them to America.

The GIs

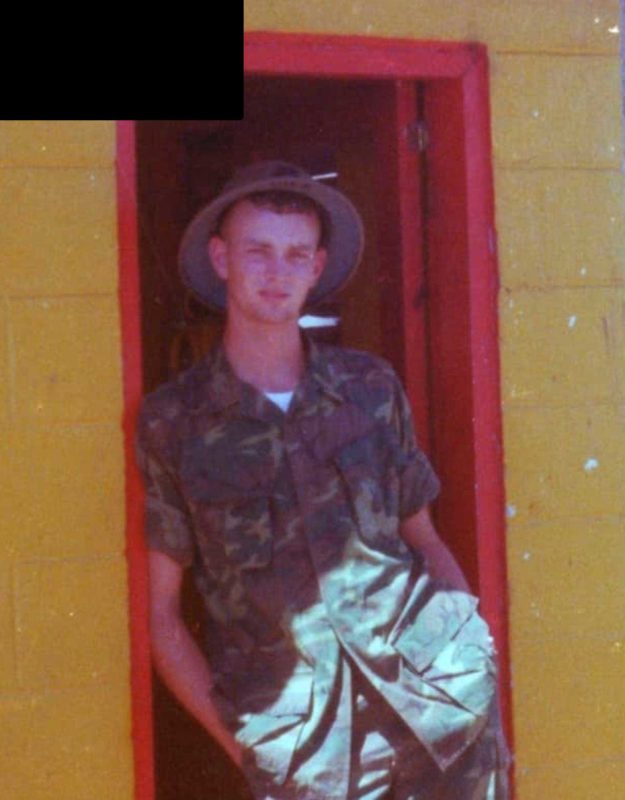

David Parscale, as a young officer in Subic Naval Base. CONTRIBUTED

David Parscale from Kansas, Missouri, now 62, was a young officer in July 1977 when he was deployed in Subic Naval Base until October 1978. He was at the Marine Barracks, working in the Provost Marshal’s Office, Special Operations Branch.

He was not romantically involved with Annie at first.

“One night about a month before I was to leave and go back Stateside. I had ripped my pants running down a suspect one morning around 3 a.m. This took place in the back of Annie’s sleeping quarters. The commotion woke her up. After everyone had gone, she came outside and asked what had happened and volunteered to sew my pants up. We were in her room talking as she fixed my pants, and then something just overcame us, and we made love. I saw her again after that,” David explains.

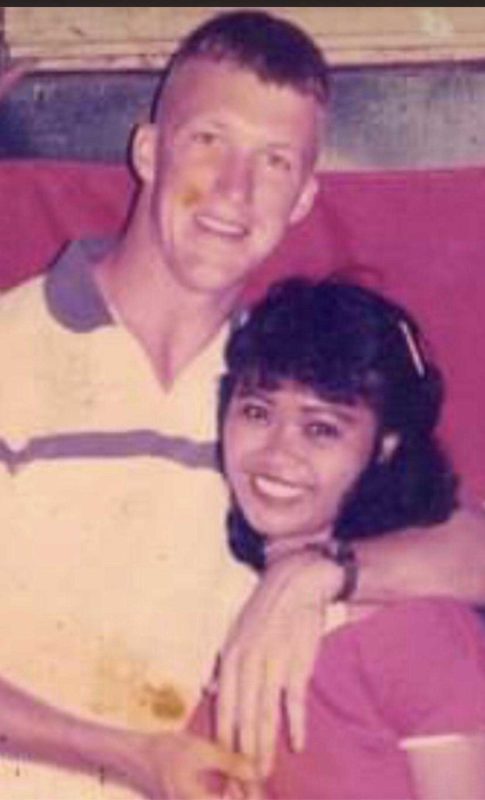

The only photo of Chad Southard and Marivic Leyson/Layson taken on December 17, 1986. Chad and Shira are still searching for Marivic. CONTRIBUTED

Chad Southard, from Georgia, came from a military family. He was 17 when he joined the U.S. Marines Corps. He was deployed to Clark Air Force Base, in a U.S. Marine Security Detachment from July to December 1986.

A few days upon arrival, Chad, then 19, met Marivic, 18, in Angeles City. The two fell in love and started dating.

Normally, before the end of deployment, servicemen were given a 72-hour window to prepare. It wasn’t the case with Chad. It was changed to a 24-hour window, without leaving the base. Marivic was expecting him but he had no way to contact her.

When Chad arrived in Japan, he asked a friend to find Marivic at her place of work. But she wasn’t working there anymore. Even the girls there did not have any idea where she was.

“I will never forget the feeling knowing that she was waiting for me and I never showed up. That is how much I cared for her. It still makes me sad when I look back on it,” Chad says.

Amerasian Immigration and Homecoming Act of 1982 and 1987

The Amerasian Immigration Act of 1982 facilitated the immigration of children fathered by U.S. citizens who served in Vietnam, Korea, Laos, Cambodia and Thailand. They must have been born after December 31, 1950, and before October 22, 1982, and provide all the necessary documents proving their claim.

The Amerasian Homecoming Act of 1987 was enacted again mainly for the Amerasians in Vietnam. The law was extended in 2009 and became the basis in the processing of the immigration of Amerasians born between January 1, 1962, and January 1, 1976. Amerasians in Japan, Korea, Philippines, Laos, Cambodia and Thailand are excluded.

“Amerasians were illegally conceived”

In 1993, Buklod Center Inc. and the People’s Recovery Empowerment and Development Assistance (PREDA), two organizations supporting Amerasians in Olongapo, together with mothers and their children, filed a class-action lawsuit against the U.S. government for monetary support.

The case was dismissed because the court decided that the women were engaged in prostitution, an illegal activity in the Philippines. Therefore, there was no basis for the claim of abandonment or for any support.

The servicemen had been discouraged from having relationships with women, particularly those working in bars. If they plan to get married, it must have the approval by the command. U.S. personnel and servicemen were provided with generic condoms and had to watch a film about venereal diseases to “scare them” into wearing protection. Chad says that the Navy corpsman would put condoms in small trash cans so that they could grab as many as they wanted. But not many used them, apparently.

Chad says: “These girls were nothing but entertainment as we were told. Just go enjoy yourself.”

‘I think I’m your daughter’

Shira’s search for her biological parents led her to Facebook groups called “I was stationed at Clark Airbase Philippines” and “Amerasian Children Looking for their GI Fathers.” The faded photo that she has became the link to her search. She was advised to take a DNA test through Ancestry.com. An American organization sponsored a DNA test kit. After completing the test, the specimen was sent back to the organization, and the result was uploaded on Ancestry.

In April 2019, Chad received a message from Shira. At first, he thought it was a prank. But when Shira explained the details and sent the picture of him and Marivic, he knew that it was real.

“I felt happy, it seemed like I had found something that was missing. I left Marivic without saying goodbye, but now through our daughter it seemed to me like we found each other again,” Chad says.

Chad Southard, now 53, had served in the United States Marine Corps until the age of 39. He is a Security Manager at Atlanta Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport in Atlanta, Georgia. CONTRIBUTED

Chad and his family are supposed to visit Shira, but it was delayed due to the pandemic.

Mae and David found each other through DNA testing in 2000. David traveled to the Philippines to meet Mae.

In 2015, under a fiancée visa. Mae was able to visit David and his wife, Brenda, and her three brothers in the United States. Mae’s relationship failed and she eventually returned to the Philippines.

“My heart went out to them both, David and her, for everything they’ve been through trying to unite as a family. I would love to be a surrogate mom to her, never to replace her own, but to be there for her in whatever capacity I can,” Brenda says.

Hope for Amerasians

Hawai’i Senators Mazie Hirono and Brian Schatz are supporting family reunification in immigration reform.

Congressman Ron Kind of the 3rd Congressional District of La Crosse, Wisconsin, introduced House Bill 1520, or Uniting Families Act of 2017, amending the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), thus providing the “admission of certain sons and daughters of citizens of the United States, which citizens served on active duty in the Armed Forces of the United States abroad.”

Kind’s bill was influenced by a former veteran, John Thomas Haines, also from Wisconsin, who untiringly lobbies for the amendments of INA. Haines has a daughter in the Philippines whom he has not yet been able to bring to the U.S. despite his acknowledgement and a positive DNA test.

Amerasians can also apply for Adult Derivative Citizenship Claim. This can be claimed by applicants 18 years old and over, born outside the United States, whose parent/s at the time of the applicant’s birth was a United States citizen.

The petition must include DNA evidence, a written agreement of the parent’s support and the information establishing that the petitioner is a U.S. citizen who served in the Armed Forces on active duty abroad. Once the citizenship claim is established, the applicant qualifies for a first-time U.S. passport.