Alleluia Panis gets the very first SF Artistic Legacy Grant Award

SAN FRANCISCO – With an artistic career that spans over 40 years, arts pioneer Alleluia Panis has been a vital force in creating new Filipino American artistic works, in nurturing artists and catalizing the awakening of Filipino artists to their indigenous selves.

Panis tomorrow will be awarded the first-ever Artistic Legacy Grant by the San Francisco Arts Commission at the annual SFAC grants meeting at the Herbst Theater.

Panis immigrated with her family to the U.S. from the Philippines in the mid-‘60s when she was turning 12. Her grandparents were already living in the U.S. for many years as a result of her grandfather’s military service in the Korean War. Her father had been petitioned by her grandfather to come and had been waiting for approval for years.

Immigration reform in the U.S. took place with the implementation of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which offered preference visa categories focusing on immigrant skills and family relationships with U.S. citizens or residents. The act, that offered no visa restrictions to immediate relatives of U.S. citizens, ushered in a big wave of immigrants with professional backgrounds to U.S. shores.

Her grandparents had been sending them in the Philippines boxes of goods from the U.S. and projected to them a vision of the American Dream.

“There was always this conversation that America is this wonderful place. And there’s freedom, and there’s lot of jobs. They painted this fantastic place.”

Like many Filipinos after the U.S. occupation of the Philippines and up to this day, both her parents were educated in the American school system.

“So they were already kind of brainwashed by the propaganda of America as a great country.”

By the time they came to the U.S., her father was already in is forties and her mother in her thirties. Her parents uprooted themselves and their family from their life and professions in the Philippines.

“It was a huge move for us. My father was fond of saying that he only had $250 in his pocket when we came,” Panis says.

They came separately within a year. She first came with her father and two siblings while her mother stayed behind to sell things they owned. The rest of the family followed as soon as they had sold everything.

“I didn’t know what would drive a fairly successful person out of a country into the United States with his eight children. It’s nuts. It’s a big adventure,” Panis says.

They first stayed in the projects in the Fillmore where her grandparents lived. Filipinos from the military predominantly occupied the floor on which they lived.

“I didn’t realize it was a horrible place until people said it was a horrible place,” Panis says. “The elevators smelled of Lysol and piss but what did I know… I was just like ‘Oh, this is America, and this is how it is. It’s a new place.’”

She had her first taste of the deceptive perception that is deeply ingrained in the Filipino postcolonial psyche. A manifestation of this is the idea of what progress is in the western context; that somehow, someway America is always better.

“Coming to the United States from the Philippines, all of a sudden you’re in this huge apartment building, it’s made out of cement, it’s solid, you have running water, you don’t have to pump for water… I thought it was better.”

From the Fillmore, their family moved to 3rd Street in a flea-infested apartment that they left after a month, eventually moving to Japan Town where they lived for years.

Panis grew up in a very religious family that was not into the arts.

“If you did any kind of art, it’s through the school or through the church.”

The first time she heard the call of the arts was in middle school when she was chosen and granted a scholarship at the SF MOMA which, at the time, had an art school at the San Francisco War Memorial and Performing Arts Center.

“For two years that was my first formal intro to art making. You’re doing it not just for fun, but your actually taking lessons.”

In high school, a friend told her about a dance class that students could take instead of doing a P.E. class. But she did not like her teacher who had a very condescending approach to her students who were mostly immigrant kids. She quit after a semester.

She then heard from a friend about a dance teacher in North Beach who taught after-school classes. It was Klarna Pinska, the influential dancer and choreographer who studied under Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn in Los Angeles and New York and who became the head teacher of the Denishawn School of Dancing in New York.

Under Pinska, Panis learned more than just dance.“Klarna actually introduced me to a different America. With my parents, it was always church, school and we all had to help out with housework, cooking, all of that.”

Pinska educated her in a different way through art and lifestyle. They would go to places in North Beach such as Café Trieste, Enrico’s and City Lights where they would attend poetry readings by the Beat Poets.

“It opened up my mind to a different way of living. It was my own private thing.”

A college prep visit to Whittier College in Southern California was the catalyst in the full unfolding of her artistic self. The program was similar to a summer camp where the visiting students took art classes and lived on campus. It was during an improv dance performance at the culmination of the visiting program where she realized the inevitable.

“It brought me to a deep connection with the audience, and that’s the point that I went ‘Oh, my gosh, I like this stuff! I really want to dance!”

She continued to work with Klarna Pinska in the 1970s and pursued dance training of all kinds from ballet, modern dance, Afro jazz to belly dancing as a result of this newfound conviction of being a dancer and an artist.

At the time, she was not very involved in the Filipino community, other than being a member of the Filipino Club in school; and she did not hang out with Filipinos and Filipino Americans.

She was taking dance classes at one of the studios in the city when she met Emilya Cachapero, who eventually became one of her closest friends, who invited her to a multi-genre artist committee and collective in the South of Market called Diwa comprised of Filipino Americans. It was the start of her connection and engagement with the Filipino community.

“I got involved with a group of young people who had a vision and were passionate about it.”

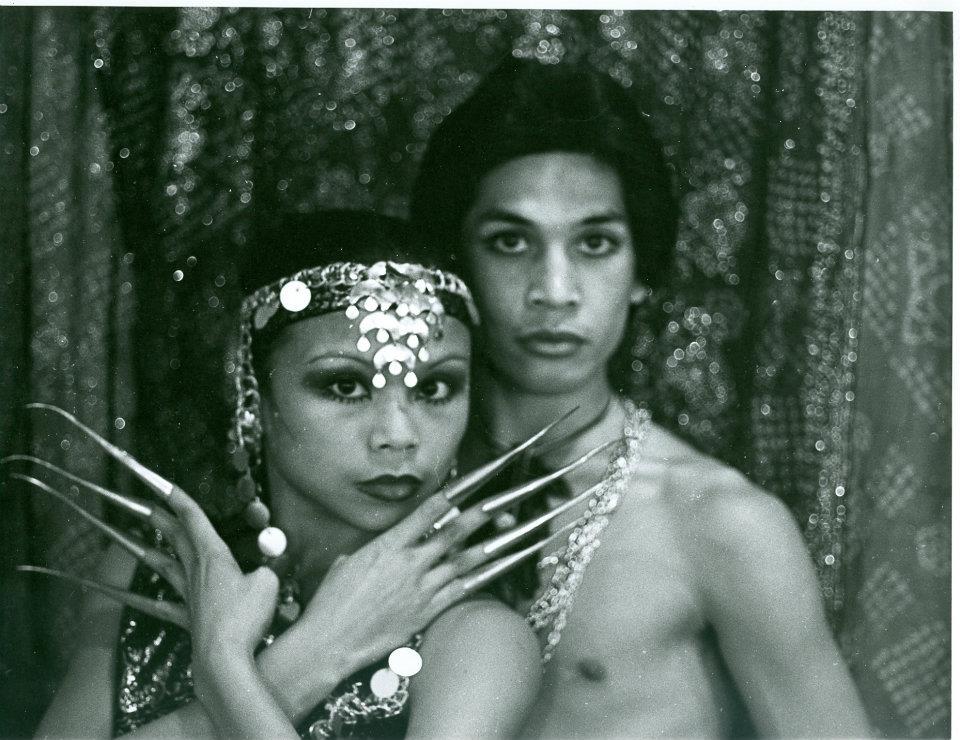

Out of this came Bagong Diwa, a dance group that was an offshoot of the collective, and the creation of new dance works.

“I was the only one in the group that had some form of Philippine dance training background, and my training was from elementary school.”

The experience of embracing her Filipino culture and heritage caused repressed ancestral memories to surface.

“Somehow the culture I grew up kicked in. It was very interesting to find myself with this information, and I kind of fell into a leadership position. That’s where my vision for Kularts started, the huge interest in creating a new language of artistic work that spoke to our experiences, creating a movement language.”

In 1975 Bagong Diwa decided to travel more as a dance company. They went to the Philippines.

“It was an eye-opening experience. I was the first person from my family to go back to the Philippines in over 10 years. It was just phenomenal. It’s such a rich culture.”

They visited tribes, learned dances, immersed themselves in the culture. It was the seed of many things to come.

She left Bagong Diwa around 1980 to strike out on her own as a solo artist. She became a soloist for the Ethnic Dance Festival, choreographed her own contemporary pieces and danced with different companies.

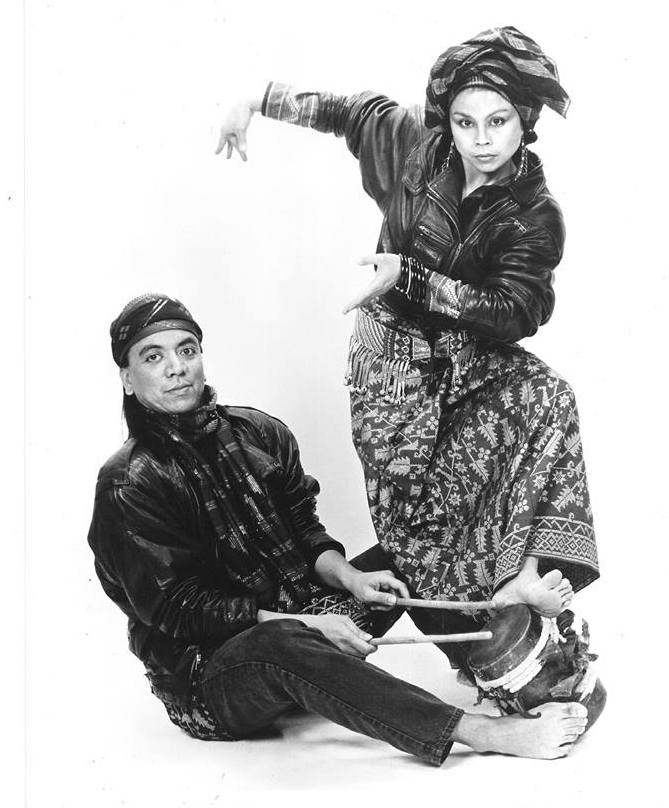

She became a member of SF Kulintang that eventually became Kalilang Kulintang Ensemble where she was choreographer. Artistic differences resulted in a split between members of the group, and Panis along with Marcella Pabros founded the Kulintang Arts Ensemble (KAE).

“One thing that was really important was in order for us to create new works, we needed to learn from a master teacher from the Philippines. And that’s when Danny Kalanduyan came into the picture.” Kulintang master Danongan “Danny’ Kalanduyan was with KAE as artist in residence and master teacher for three years.

“I am not a traditional folkloric dance choreographer. I’m interested in the story that we’re telling. How does it relate to us being Americans, being in this place? A deep inquiry into indigenous cultures and tradition, not just skimming the surface.”

The first time KAE did an American piece was in collaboration with Fred Ho’s Asian American Jazz Ensemble-Bamboo That Snaps Back that Panis was also a member of along with composer and pianist Jon Jang.

This intense and highly creative period that started in 1985 led to a group that was burnt out 10 years later.

“I’m the only one who stayed all the way. I had to shift what it is so that the organization doesn’t go to waste.”

Kulintang Arts Ensemble became Kularts, a presenter of contemporary and tribal Filipino arts.

“Kularts has always been a platform for my own artistic vision. From the very start, my vision was to create works that come from my own perspective, my own experiences. I felt like I had a story to tell, that I had something to say.”

With Kularts, Panis has nurtured numerous artists and presented works by artists from the U.S., the Philippines and the diaspora. She has also used it as a platform to cultivate Filipino American culture and arts, laying the groundwork for future generations.

The first-ever Artistic Legacy Grant Award will be presented to Alleluia Panis at the Herbst Theater in the same building where she first attended art classes many years ago.

According to Kate Paterson-Murphy, director of communications, San Francisco Arts Commission, “the program offers one annual grant to an arts organization that is deeply rooted in a historically marginalized San Francisco community to recognize its longtime artistic director and that person’s leadership in the cultural community.”

The artistic legacy grant acknowledges the impact of an artistic director that has served the organization consistently for 25 years or more.

“Alleluia and Kularts embody the spirit of this grant. Her contributions to San Francisco’s artistic and Filipino communities cannot be measured. An innovator and an activist, she was part of a generation of beloved artists who fought for the establishment of the Cultural Equity Endowment Fund, of which this grant is a part,” says Paterson-Murphy.

“Today, she continues to hold space for emerging and established Filipino artists and cultural bearers through her work as a choreographer and artistic director, and through her activism with SOMA Pilipinas. This award pays tribute to her vital contributions to San Francisco’s cultural landscape. We are honored to celebrate her legacy at our upcoming Grants Convening on September 26,” Paterson-Murphy adds.

“I’m shocked and elated and humbled,” Panis says. I’ve spent so much difficulty in the city in terms of being part of a community that’s not really vocal or not really seen, and it’s even tougher in the arts. I never thought that I would be honored in this way. Even though I’m very grateful to the city because this is how I got turned on to the arts and got nurtured in the arts, I didn’t think I was going to be recognized for the work that I do. This award is super gratifying. The surprise is tremendous.”

Looking back, she has this to say about her rich artistic life: “It’s never easy being an artist. You’re wired as an artist and you cannot change it. One is that you find a way to do it the way I did it; the other is to find a straight gig to support your artistic life. I’m not gonna say be an artist because it’s so glamorous and all of that; but if you choose to you can make it happen. The fact that I’m here… you can do it, I mean, you can do it!”