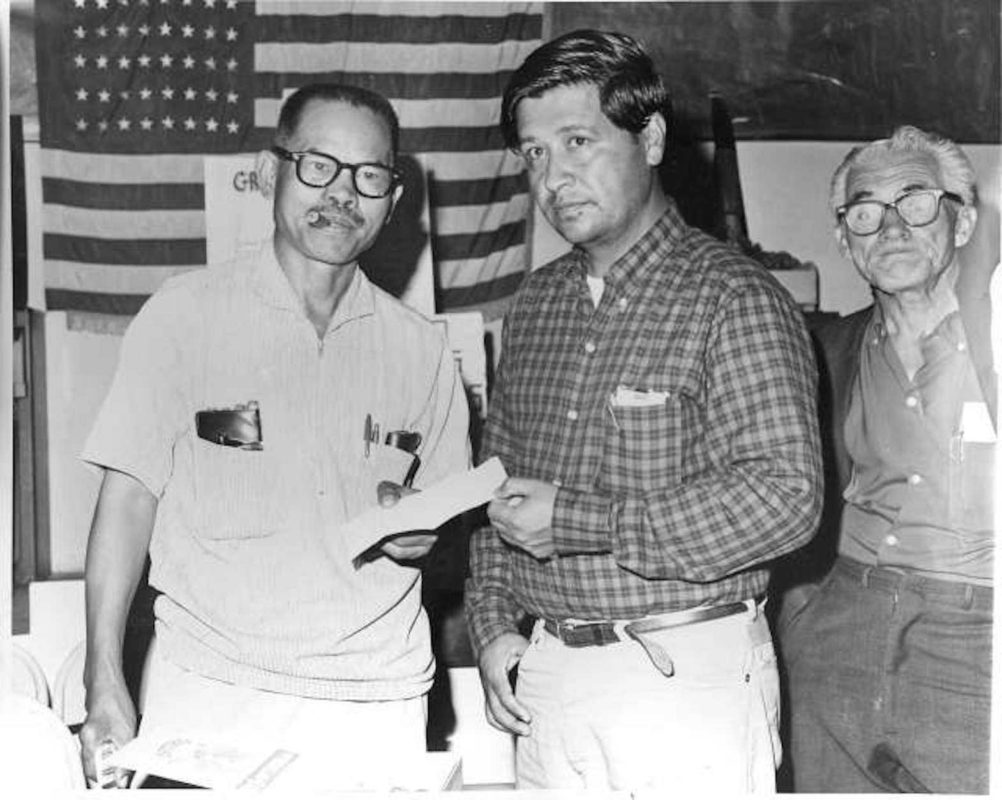

Larry Itliong (left) with Cesar Chavez during the Delano Grape spike. HANDOUT

This Labor Day, here’s a perennial question that must be asked again and again at this time every year until every single one of us gets it right.

Can you name the great Filipino American labor leader who’s a household name or should be?

Perhaps a name equal to Cesar Chavez? If an answer doesn’t roll off your tongue, I can’t blame you.

The name’s been missing from history books, so how would you know (unless you read my columns?)

Still, not knowing a name only adds insult to injury because the real reason Cesar Chavez is known is largely due to one Larry Itliong.

Remember him. He’s been forgotten too long.

If you knew his name, congratulations. But then read and re-read the next paragraph for the single fact that rectifies a major omission from history.

Larry Itliong, born in San Nicolas, Pangisinan, Philippines, came to the U.S. in 1929, when the Philippines was a colony. Itliong was one of the group of men known as the “Manongs,” whose official status was colonized “American nationals.” They were looking for opportunity and found work as migrant workers in California’s fields and Alaska’s canneries. But he made his mark by being the one who actually began the historic 1965 Delano Grape Strike in Delano, California.

Yes, the very same grape strike that made Cesar Chavez famous wasn’t Chavez’s idea.

It was Itliong’s vision to merge labor issues with civil rights to form one massive social justice movement that emanated from the breadbasket of our nation, the Central Valley of California.

The strike was declared on Sept. 5, 1965 by Itliong’s Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) of the AFL-CIO at the headquarters in Stockton. But a strike vote had to be taken about three hours away by car in Delano, where the growers were and where most of the workers lived. On Sept. 7, the workers gathered at the Delano Community Center to make history. Their demand for $1.40 an hour was rejected by the growers. It was up to Itliong to call the question. Unanimously, all the workers raised their hands and the strike was on. The workers walked out the next day on Sept. 8.

The AWOC Filipinos went directly to the streets to picket. Chavez’s group, the National Farm Workers Association, wasn’t a real union at the time and stayed on the job. Chavez wasn’t convinced a strike was the answer.

It took Itliong to convince him that the aging Filipino work force needed the young blood from the new migration of people from Mexico. Chavez eventually joined Itliong, and their two groups formed the United Farm Workers. But it was always a clash of styles.

Itliong had a cackling laugh and was tough, crass and ready for a fight. Chavez always had a quiet, solemn nature, with a preference for non-violence and hunger strikes.

As my old friend, Stockton Filipino community leader Ernie Mabalon, once criticized Chavez, “Marching behind the statue of the Virgin Mary is not a strike.”

Other Filipino Americans leaders like Philip VeraCruz and Pete Velasco emerged within the UFW. By 1971, Itliong had left the UFW, but his moment in history had been done.

He was the sparkplug of the movement. And our unanimous American labor idol, right?

Well, not exactly.

50th anniversary plus five

At that very hall in Delano five years ago, more than 500 people gathered to remember the 50th year anniversary of the strike, and to honor the foresight and courage of Itliong.

I had driven there with my buddy Dillon Delvo. Once there, I interviewed Chavez’s son, Paul, who signaled to the crowd it was time to acknowledge the Filipinos were left out of the narrative.

That’s what most people can agree on.

“There are names lost in history, and today’s ceremony goes a long way to rectifying that,” he told me. “Of course, there were some hard feelings. Who would not be offended if they felt their contributions weren’t recognized.”

Five years later, things have progressed slowly in terms of rehabbing the history. Itliong is getting some of the notoriety and the recognition he deserves. For example, his face was among the logo images in the new PBS documentary on Asian Americans.

But to Alex Edillor, president of the Filipino American Historical Society’s Delano Chapter, Larry’s still not quite where he should be, and maybe will never be. Edillor says even in Delano where he grew up, there’s still an uneasiness about what Larry and the Filipino strikers did.

“There’s a young generation here that doesn’t know Itliong even in his home town,” Edillor told me by phone. He said that even five years ago, the number of people coming from the Bay Area and Los Angeles to honor Itliong at the 50th was greater than the number of Delano locals. Edillor said most of the Delano community had moved off the farms and into the middle-class as professional workers.

In some ways, that was both progress (they were no longer ag workers). But it was a definite regression too. Itliong seemed to be forgotten by the Filipino community he fought hard to uplift..

Edillor recognizes the conflict. He says it was a big step for his mother and father to take that strike vote with Itliong to walk off the job.

“95 percent of the strikers were afraid,“ he told me. “It was frightening, but they did it.”

It was Itliong who convinced them it was time to stand up and fight.

Edillor, who was just in grade school at the time, recalls when his father came back from a picket line and found out the stipend promised was just $5 a week. “He was devastated,” Edillor told me. “It wasn’t nearly enough [to cover family expenses]. So you know the great strike wasn’t the cohesive movement in Delano itself.”

But the strike had an impact on national and global economies, affecting the importation of table grapes, as other fresh produce, and grape products like Gallo wine from California.

Edillor still gives tours to college kids in Delano about the strike. And this new generation of Filipinos and Asian American history students appreciates the impact Itliong had.

He also tells them about hanging out with Itliong as a teenager. “We lit his cigars,” Edillor said with a laugh. He also helped Itliong on what would become his passion after the UFW—politics beyond the union.

Itliong started the Filipino Voters League and, with Edillor and two other young buddies, canvassed the valley doing real grassroots politics.

“We worked with him until he couldn’t work anymore because of ALS, and we would be his hands and feet walking around the community with flyers and stuff,” Edillor recalled.

Itliong’s endorsements meant a lot at the local level, like when he got a win for a young progressive in the conservative valley. But he also was a national player and a supporter of Robert F. Kennedy for president in 1972. Other groups would offer him money to get him to back another major candidate. But Itliong never budged. He was as loyal to Kennedy as he was to the Filipino community.

The memory of Itliong helps Edillor feel the same buzz he gets after giving college kids a tour about Delano and the old Filipino unionists who followed Itliong and started the grape strike.

“I tell them, if you’re encouraged by the story of the manongs in Delano,“ Edillor said, “then continue that legacy through activism in any election.”

Like the upcoming one in November.

Let Itliong’s spirit—the one that sparked the grape strike 55 years ago —get us all to register and vote.

Emil Guillermo is a journalist and commentator. He is an Inquirer.net North American Bureau columnist. Twitter @emilamok. Listen to his podcasts on amok.com. See him on Facebook @fanhnsmuseum