Monuments and the power of memory

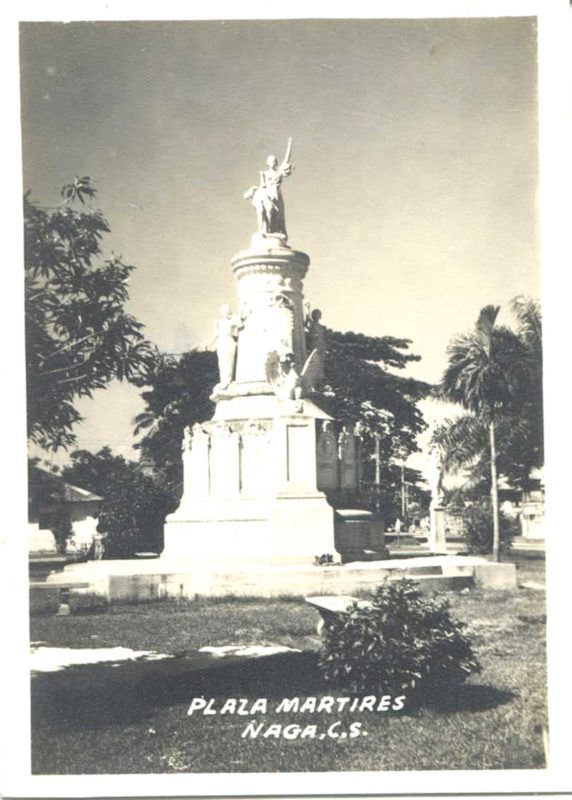

A pre-war photo of the Plaza Quince Martires in Naga City. The monument honors the 15 martyrs of Bicol who were executed by the Spanish in 1897 for rebellion. (Photo: Savage Mind: Arts, Books, Cinema

The #BlackLivesMatter protests in the United States have brought renewed attention to the power of monuments and the histories they represent. In the Philippines, a good number of our monuments glorify both our fight for self-determination and the contributions of our colonial overlords. This juxtaposition appears to be a contradiction or a confused representation of our history – why highlight both when we are still trying to establish a national identity?

As one of the first to gain independence from colonial administrations in Asia, the Philippines had more than half a decade to craft its national identity. However, it has eluded us because of the reification of colonial structures that continues to elevate regionalism by the maintenance of the divide-and-conquer strategy.

In a previous essay, Marlon Martin and I argue that our century-old educational curricula have contributed to our inability to develop an inclusive identity that can facilitate to break parochialism (Read: The Ifugao, cowboys, and assimilation through education). What’s worse is that this is also reflected in class segregation, appearing to favor modern-day mestizos and Ilustrados. The debate on whether to venerate Rizal or Bonifacio is a manifestation of this class distinction. Yes, Filipinos did not have much say in the decision to make Rizal the National Hero, but after 75 years of independence, we should move beyond this debate and take a more nuanced understanding of the complexity and diversity of our histories.

Take for example the multitude of Rizal monuments across the country – or around the globe. When I was growing up in Tinambac, Camarines Sur, our town plaza had a Rizal monument that was spruced up once a year, in preparation for Rizal Day festivities. But after that event, the monument is a target practice for kids using tirador (slingshot). If Rizal is to be the national hero, the educational system is not doing a good job at elevating his ideals to our students.

So, in this sense, our monuments fail to live up to their purpose, to serve as repositories of memories and narratives (Read: The struggle for historical symbols). Perhaps, it has to do with the Eurocentric basis of monument-making. As a country with a long history of colonial experiences, these monuments were defined for us, definitions that forced us how they should be remembered.

We don’t have a lot of monuments that help us face the dark and gruesome part of our histories. If we have, they are not part of the mainstream (i.e. Bantayog ng mga Bayani [Monument of Heroes], Bataan Death March). We don’t have monuments, as places, that serve as an apology (e.g. Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Bikini Atoll) to remind us of the atrocities we directed at our fellow human beings.

Monuments are spaces but they become places when we attach meanings to them. These are part of our cultural landscapes that define who we are. But these meanings are sometimes imposed by placemakers who favor a certain narrative. These places compel us to remember memories given to us through formal education or through oral histories. The visual landmarks serve as sensory stimuli to heighten our sense of the place and/or memory.

Thus, in this case, we have the power to change the narrative. We can bring down the monuments that glorify our dark past, but we can also keep them as remembrances of injustices; to help our future generations to remember how our forebears fought for our freedom. For example, there is a Miguel Lopez de Legaspi monument in Manila that memorializes the subjugation of the Philippines by the Spanish in the 16th century. It marked the beginnings of the Philippines as a nation, but it also portended 300 years of exploitation.

The return of the Balangiga Bells is an example of this memory. Although the bells represent our bajo de campana colonial encounter (the bajo de campana, or literally, under the sound of the bell, forced the relocation of Philippine communities within the hearing confines of the church bells), they also remind us that we are capable of co-opting colonial ideas, that we are not just recipients of what is given to us, we innovate, and we make things work to our own benefit. We make our own history out of displacement.

On another hand, monuments usually represent the contribution of the elite in our history. When I moved to Naga City for my high school education, I pass by the Quince Martires monument and I used to think of it as our struggle against Spain. But now, I reflect on how it represents the invisibility of the disenfranchised. Yes, the monument talks about our fight against colonialism, but it shouldn’t be elitist; it shouldn’t erase the marginalized.

This displacement is exemplified in UNESCO designations of heritage sites. For example, we highlighted the recent origins of the Ifugao Rice Terraces and how the UNESCO designation has some serious ramifications in terms of presenting the Ifugao as a static and unchanging people (Read: Demystifying the Age of the Rice Terraces). Since UNESCO’s focus is on conservation for tourism purposes, the cultural and historical contexts of sites have been largely ignored. The UNESCO listing of the Ifugao Rice Terraces embodies the western tradition of conservation, overlooking the cultural context of rice and rice production in the region.

The concept of Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) as applied in the UNESCO nomination process becomes problematic because OUV is based on the Enlightenment philosophy. The OUV emphasizes cross-cultural generalizations to establish universal laws of culture, but in practice OUV had the effect of erasing variability, reducing humanity to a set of standardized themes.

This apparent failing of previous UNESCO designation was addressed by the Nara Document on Authenticity (Read: Nara UNESCO Document), which addressed the need for broader understanding of cultural diversity and cultural heritage. However, after almost two decades, this directive has not been widely applied.

This OUV application highlights how our spaces were defined for us. But we can always counter these definitions by involving local communities in expressing their own representation of themselves. It is in this sense that we see the value of community museum as areas for knowledge production and contestations to counter national narratives. They facilitate knowledge dissemination to challenge authoritative accounts that are reified by national agencies. Museums, similar to monuments, are places that hold community memories.

Community museums are integrated into the community’s daily life, particularly when they facilitate community cohesion. In Ifugao, the Indigenous Peoples Education Center in Kiangan serves as a venue for activities that brings together community members. The top-down focus of national museums and profit agenda of private museums are counteracted by community-run museums/centers. Local stakeholders need to feel a sense of ownership in a museum and be involved in its development for it to be sustainable in the long run.

It is in this sense that we can argue that monuments are important. We can topple them to channel our anger, but there is a need to get the meaning out to future generations. There is no question that statues and monuments that glorify racism and prejudice have to go, but we need this historical moment to engage our future, and as redress for injustices.

Monuments are markers of history. Let’s use them to elevate the history of the alienated, to make the invisible visible. National agencies and international institutions can strengthen their mandates by engaging communities. We are now our own placemakers; let’s fight to get our meaningful definition of our own spaces.

Stephen Acabado is associate professor of anthropology and a member of the core faculty of the Cotsen Intsitute of Archaeology at University of California, Los Angeles. His archaeological investigations in Ifugao, northern Philippines, have established the recent origins of the Cordillera Rice Terraces, which were once known to be at least 2,000 years old. Dr. Acabado directs the Bicol and Ifugao Archaeological Projects and co-directs the Taiwan Indigenous Landscape and History Project. He is a strong advocate of an engaged archaeology where descendant communities are involved in the research process. This essay is part of a longer chapter in an upcoming book on the archaeology of Philippine indigenous history co-authored by Marlon Martin.

Marlon Martin is an Ifugao who heads a non-profit heritage conservation organization in his home province in Ifugao, Philippines. He actively works with various academic and conservation organizations both locally and internationally in the pursuit of indigenous studies integration and inclusion in the formal school curricula. Along with Acabado, he established the first community-led Ifugao Indigenous Peoples Education Center, the first in the region.