Unprecedented exhibit of PH art at SF’s Asian Art Museum

Native Song, 1999 By Santiago Bose (Filipino, 1949 – 2002) Oil on canvas with mixed media and color process prints on paper Gift of Malou Babilonia, 2007.80

SAN FRANCISCO — An unprecedented survey devoted to historic and modern artworks from the Philippines is now on view until March 11 next year in the Tateuchi Thematic Gallery, Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.

Philippine Art: Collecting Art, Collecting Memories is the result of more than a decade of study and collecting by the museum’s curatorial team — a “labor of love” to expand the institution’s holdings in this oft-overlooked area.

This is the first exhibition ever mounted in the United States of Philippine art spanning from the precolonial period to today.

It explores the Philippines’ diverse artistic practices through 25 rare and compelling works: traditional carving and weaving; Islamic metalwork; Christian art from the colonial period; and modern and contemporary painting and mixed-media.

This rich variety comes together to tell the sometimes unfamiliar story of how the Philippines — an island nation positioned along ancient trade routes between China and India and, later, Europe via the Americas — has for centuries been a center for artistic exchange and innovation.

“The artistic culture of the Philippines has been marked by a history of invasion, resistance, accommodation and adaptation,” explains Natasha Reichle, who as the museum’s associate curator of Southeast Asian art spent years acquiring the artworks organized into this exhibition.

Chest ornament, approx. 1800-1900 Philippines; Luzon island, Isneg people Mother-of-pearl, glass beads Gift of the James and Elaine Connell Collection, 2012.55

“What has been fascinating is seeing how contemporary artists draw upon aspects of this complex legacy to create new works, works that are celebrated in the Philippines and valued in a global art market that is beginning to appreciate their beauty, originality and sophistication.”

Spread across numerous islands, the tropical Philippines was originally animist. With the influx of Muslim traders, many peoples, especially in the south, converted to Islam by the 1400s.

Now largely Catholic — the result of hundreds of years of rule by Spain — the nation spent the early-20th century under American colonial government followed by Japanese occupation during World War II; the Philippines only gained independence in 1946.

This long relationship with the United States precipitated successive waves of immigration, with Filipinos now the second largest ethnic Asian community in the country.

“Ironically, the Philippines’ colonial history and Christian artistic legacy placed much of its art outside familiar ‘Asian art’ storylines of Hinduism or Buddhism, which may have led to its exclusion from our museum’s original founding collection,” explains Reichle.

Saint Isidore the Farmer and worshippers in a field, approx. 1750-1800 Philippines Oil on wood panel

“Luckily for our visitors, this is a story that wants to be told. We have pieces in this exhibition acquired by donation, given directly from artists and collectors, even from the families of former missionaries and on-the-ground field researchers. The backstory of how we acquired every artwork mirrors the fascinating history of the Philippines.”

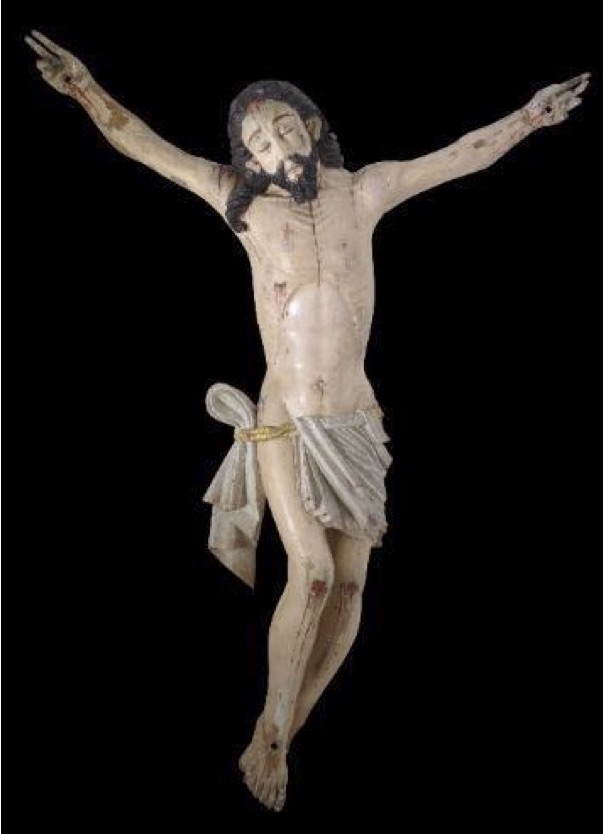

Crucified Christ, approx. 1650-1750 Philippines Colors on wood Acquisition made possible by the San Francisco-Manila Sister City Committee, 2016.163

Philippine Art: Collecting Art, Collecting Memories is divided into three sections:

• The first section focuses on works with roots in precolonial culture, including textiles, jewelry, sculpture and vessels serving ceremonial or practical purposes. Highlights include handmade and embroidered garments from female master-weavers as well as belts and ornaments fashioned from a mix of trade goods and indigenous materials.

• The second section centers on the impact of Christianity on Philippine art. Highlights include two exceptionally expressive statues of Jesus and Mary (17th–18th centuries) only acquired this past year. Such fine older examples of Christian art are extremely difficult to find outside of the Philippines and it is rare to find them on view in the United States.

• The final section of the exhibition showcases well-known Philippine modern and contemporary artworks, from early masters like Fernando Amorsolo and Anita Magsaysay-Ho, to activist art during the rule of Ferdinand Marcos, to mixed-media works by Santiago Bose and Norberto Roldan.

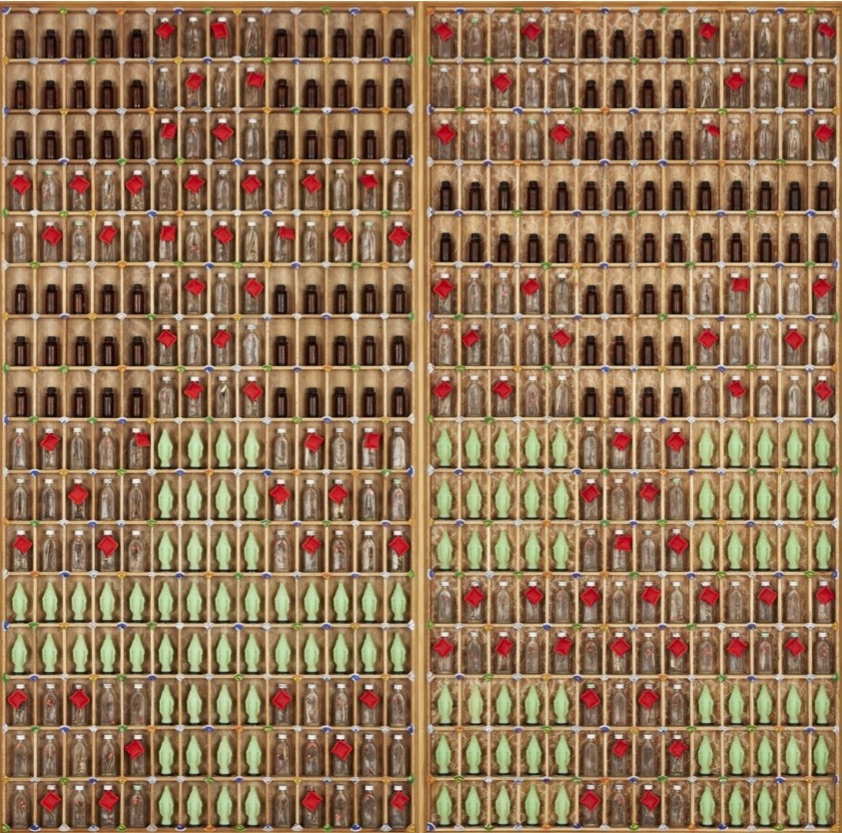

Everything is Sacred #1, 2009 By Norberto Roldan (Filipino, born 1953) Wood, glass, plastic, metal, and cotton Acquisition made possible by the San Francisco-Manila Sister City Committee (2014-15), Therese Francia Martin, Catherine Cheung and museum funds., 2015.33.a-.b

Amorsolo’s vibrantly hued yet humbly nostalgic representations of folk life, like Farmers working and resting (1955), have made him a beloved figure in the Philippines, while Roldan’s sought-after “curiosity-cabinet” assemblages, like Everything is Sacred #1 (2009), evoke the overlapping layers of history that inform cultural identity in the Philippines.

“The San Francisco Bay Area is home to one of the most important communities of Filipino ancestry outside of Asia, yet until now we have not been able to fully convey the real dimensions of this nation’s rich creative culture,” says Museum Director Jay Xu.

“We are incredibly pleased to present these critical additions to our collection, which reflect not only the heritage of so many in our hometown, but which help visitors understand the inherent diversity of what it means to be Asian and underscore the Asian Art Museum’s role in making this diversity both relatable and relevant.”