Manong ‘Benny’s Altars’ exhibit bares diaspora’s roots

“Benny Gallo and His Altar” by Tony Remington. INQUIRER/Wilfred Galila

SAN FRANCISCO – Benny Gallo was a well-dressed gentleman who belonged to the manong (older brother or elder) generation. The manongs were the first wave of Filipino immigrants who came to the United States, starting in 1906 with the importation of Filipino farm laborers by the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association. Those who came in the 1920s and 30s and worked as seasonal migrant workers in farms in the west coast and salmon canneries in Alaska.

Many of the manongs came to what was then Manilatown on Kearny Street, a five-block district from Bush Street to Jackson Street of Filipino residences and businesses. The encroachment of the Financial District brought about by the urban renewal and redevelopment movement in the mid-‘60s led to the destruction of Manilatown, including the International Hotel where many of the manongs lived.

After the forced eviction of the I-Hotel in April 4, 1977, many of the manongs moved to SRO (single room occupancy) housing around the area. Gallo took up residence at the Royal Hotel on Clay Street. It was there in his small room where he lived alone that he created his altars.

“Carlos Bulosan” by Mel Vera Cruz. INQUIRER/Wilfred Galila

Inspired by Gallo and his creations, a joint exhibition of new and old works by Filipino American artists Tony Remington, England Hidalgo, and Mel Vera Cruz called Benny’s Altars is on view from September 27 to November 27, 2019 at the I-Hotel Manilatown Center at 868 Kearny Street.

Featuring photographs, paintings, rubbings, and installations, the exhibition was conceived by Remington who had first met Gallo in 1977. “After the I-Hotel eviction, all the manongs had to live in all the adjacent hotels. We ran a meal program that was spearheaded by poet activist Al Robles. My duty in the program was to deliver meals to the homebound citizens. I had seven to eight manongs I had to deliver to. Benny was one of them.”

Remington, a multidisciplinary artist, came to prominence as a photographer for documenting the lives of the manongs who lived in the I-Hotel until its fall in 1977. He was one of the artists who frequented the Kearny Street Workshop, then a collective of Asian American artists and activists headquartered in the I-Hotel.

Remington started photographing Gallo during his visits and noticed “these things that started appearing in his room. Being an artist and a photographer, I was very curious about these things.”

Gallo had created three altars made from found objects, “an empty suitcase half, a conglomeration of Styrofoam packing that seemed to come from stereo speakers, and flat Styrofoam pieces covered with aluminum foil.”

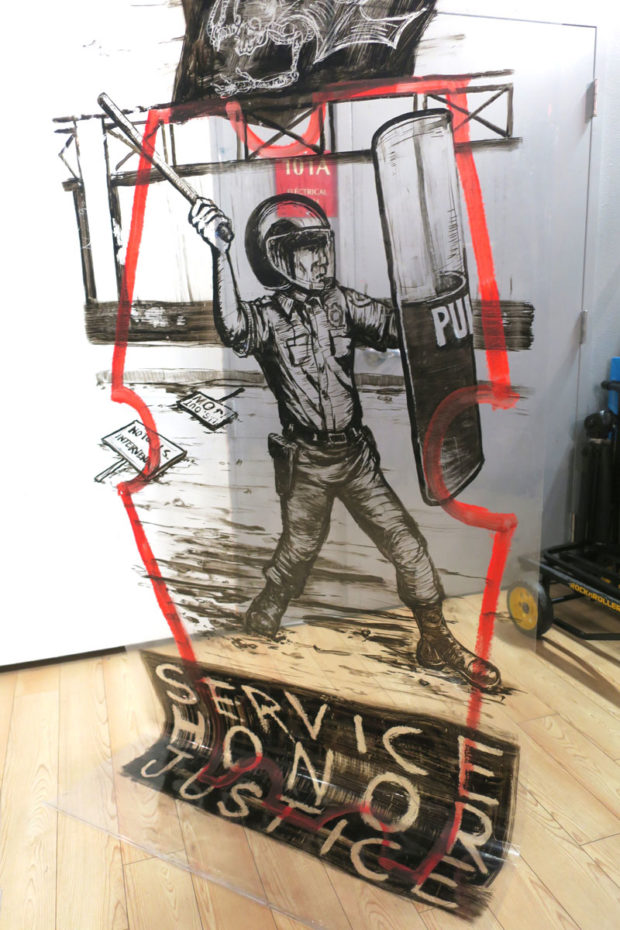

Painting on acetate installation by England Hidalgo. INQUIRER/Wilfred Galila

These altars were titled Wandering Sight, King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, and The Fighting Lady. Remington was fascinated.

“He would start telling me stories like ‘the little people were here again last night dancing’ around the piece he called Wandering Sight. I walked in one day, and he said, ‘she’s crying,’ and he meant The Fighting Lady. He would look at it and his eyes would wrinkle up and he’d say, ‘I don’t know why she’s crying?’ He was really puzzled.”

Remington took Gallo seriously. “A lot of people will think that it’s just an old man experiencing dementia or like Alzheimer’s or something like that, but I don’t think of it that way at all. As an artist, I saw him as an artist.”

Remington would “just stop and stare” at these altars and “gaze at them with this kind of reverence. “Benny’s altars are about liberation, spiritual liberation, which is not exclusive of what you’re particularly interested in.”

“Ligo Sardines” by Mel Vera Cruz. INQUIRER/Wilfred Galila

Remington was drawn to other forms of spirituality and belief systems after being cynical of the hypocrisy of the religion that he grew up in. Born in Santa Ana, Manila, Remington came to the U.S. with his family when he was a year old. They settled in the Haight-Ashbury district where he grew up and experienced many facets of American life, including racism. “There was a person who told my father to stand in the back of the church. He didn’t want him standing next to him. I was very cynical about the hypocrisy of Catholicism, and on many historical levels.”

For Remington, Gallo’s altars represented alternative ways of worship and reverence for the spirit that thrives beneath Philippine colonial and diasporic history. Remington describes his encounter with Gallo and his altars as his “jump off point” for his “long-term journey” to get in touch with his roots as a Filipino.

“Not just going to the Philippines and learning how to handle Manila, but really trying to dig deeper into our pre-colonial spirituality, on what that culture that we were before colonialism, and to recognize that we never lost it. I really thought I was experiencing magic when I left his room each day. I’d just think ‘wow, this has gotta be the coolest thing that ever happened to me at this job.”

Benny Gallo holding up a piece of one of his altars. TONY REMINGTON

Benny’s Altars was originally planned as Remington’s solo exhibition of his photographs, paintings, and drawings. “This was Tony’s slot for his exhibition, and then he just thought about inviting us, of having a group exhibition,” says Hidalgo.

Remington reasons that he invited Hidalgo and Vera Cruz because “that’s the Filipino way, group shows. I’m hoping that we can do another show, find a larger venue, and have more artists. That’s part of what I think my function as an artist.”

Remington compares Hidalgo and his art to one of Benny’s altars, The Fighting Lady, because of its confrontational quality. “I think it’s the punk aesthetic, the attitude that he saw in Benny’s altars and how he constructed his altars. Siguro nakita niya rin yun doon sa mga drawings and my old works (Maybe he also saw this approach in my drawings and old works),” says Hidalgo.

Hidalgo’s installation consisting of ink on acetate illustrations were done in response to a violent dispersal of indigenous people protesting in front of the U.S. Embassy in Manila against the decimation of their population and displacement from their ancestral lands by corporate plunder and militarization.

It echoes the history of displacement of the Filipino community in San Francisco starting with Manilatown and the I-Hotel. “It’s all about having [a] home, all about gentrification, people taking over other people’s country or space,” says Hidalgo.

Artists Mel Vera Cruz, England Hidalgo, and Tony Remington at the opening of their group exhibit “Benny’s Altars” at the I-Hotel Manilatown Center. INQUIRER/Wilfred Galila

His other works on exhibit are rubbings of sidewalks of streets around the Dimas Alang housing project in the South of Market, bordered by Third, Fourth, Harrison, and Folsom Streets, that currently bear the names of Filipino heroes—Rizal, Lapu-Lapu, Bonifacio, and Mabini. This method was inspired by the ancient Buddhist practice of copying and preserving scriptures that were etched in stone.

“In order to pray, to read those scriptures, you had to go to the place. And what they did was they started rubbing the paper with ink so you can take home the scriptures, take home a print,” says Hidalgo.

Furthermore, these pieces were a reaction to a December 28, 1979 SF Chronicle with the title Exotic Street Names. The article is about the changing of the old Irish street names to the aforementioned street names of Filipino heroes after Filipinos moved into the area formerly occupied by the Irish before the 1906 earthquake.

SF archivist and leading expert on San Francisco’s history Gladys Hansen, did not like the changing of the street names and was quoted as saying, “Our street names are being turned around for ethnic groups. We’re trying to make too many people happy, and in doing so we are ruining our city. We can’t tear our city apart for every passing fancy. What if, in 20 years, some other ethnic group comes in and wants to change it again?”

Hidalgo wanted this piece of the city’s history preserved through his rubbings. “It’s about documenting the existence of communities and their micro histories,” says Hidalgo.

Vera Cruz admires Remington’s sensibility towards living and making art. “He doesn’t even know na ang works niya ay importante, so wala siyang pakialam kung ano ang gawin namin (He doesn’t even know that his works are important, so he doesn’t care what we’re going to do),” says Vera Cruz. “We can do anything. Yun ang gustong-gusto ko kay Tony (That’s what I like the most about Tony).”

Vera Cruz started as an art student in the Philippines, from what he describes as being nailed to western art forms and materials. “Hindi kami tinuruan ng Philippine art, indigenous art (We were not taught Philippine art, indigenous art). Art was supposed to be European based, so oil paint, ‘di ba? (Isn’t that so)?”

Vera Cruz questioned this imposed rule and from then on started using other media, from different types of paint and found objects, as materials for his art. “We are the artists, we are the ones who are going to dictate what the medium will be,” says Vera Cruz.

Vera Cruz, who worked for many years as a printer in a shop, realized the connection that Remington saw in him and his art with Gallo. “My philosophy in life, in art, is that art is not separate from life,” says Vera Cruz. “So, whatever my job is, that is also my art. I realized that Benny Gallo is the same. He does not let himself be defeated by whatever calamity comes to his life. Being an artist is about imagination.”

Remington is very pleased with the group exhibition and how it has deepened his connection to his roots. “I’m so proud to be showing with them. I joke that it’s really my coming out party show, because I’m really feeling a much deeper connection to the Philippines, and that’s what I always wanted because I lost my roots.

“I became completely Americanized. When I think about years of colonialism we’ve been subjected to and how it really messes up with your thinking, I look at how I was and used to be, I’ve gone through many, many changes, trying to be different cultures, trying to be black, trying to be Mexican, trying to be Chinese or Japanese, but I’m really just Filipino, Fil-Am.”