Food bank worker helps fight hunger in 2 California counties

Second Harvest Food Bank worker Patrick Manigque leaves for a resource fair to connect people in need to free food and other services. INQUIRER/CM Querol Moreno

SAN MATEO, California — Where there’s a resource provider fair, chances are Patrick Manigque will be standing tall over a table loaded with postcards and flyers about the services offered by a 45-year-old community -based organization.

Over lunch break between speeches at the recent Seniors on the Move at the San Mateo Expo Center, for instance, Manigque wolfed down his sandwich instead of abandoning his post as attendees streamed in front of him.

He flashes a welcoming smile at everyone who stops by his station, eager to share how to access food distributed in Santa Clara and San Mateo Counties by Second Harvest Food Bank (SHFB) based in Silicon Valley.

He points to eye-catching flyers in English, Chinese and Spanish listing his agency’s programs: free food; prepared meals served at community sites; meals for children throughout the schoolyear and summer break; a partnership helping applications with CalFresh — formerly known as food stamps, and food vouchers and nutrition workshops for expectant mothers and children.

“Everyone needs a little help sometimes,” Manigque, 51, echoes one of the maxims of the nonprofit founded in 1974 in San Jose.

“SHFB helps fill the hunger gap in the community by providing healthy, nutritious food to families in need,” he tells inquirer.net. “Families in turn do not have to choose between paying rent or eating healthy food and could use part of what they save towards paying for rent, clothing, etc.”

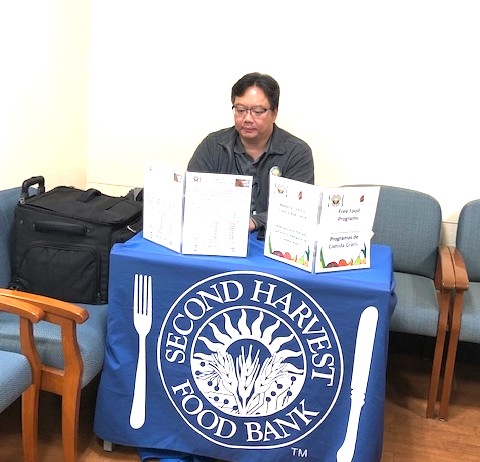

Patrick Manigque awaits potential clients at his station at the San Mateo County Human Service Agency office in Daly City. INQUIRER/CM Querol Moreno

Since 2016, Manigque has owned the title of Food Connection Field Specialist. He is among the food bank’s ten Filipinos of 300 diverse employees. He would be the first to acknowledge that while the counties of San Mateo and Santa Clara may have the highest housing values and income levels in the United States, the new wealth benefits a limited sector and drives up the cost of living.

The disparity excludes many communities outside the tech industry and the recently arrived in this country. For them, Manigque and his colleagues zip up and down Interstate 101to prevent the spread of hunger and malnutrition.

Service

By his count, his team serves “approximately 260,000 people a month (and) half of what we distribute are fresh produce; over half of our clients are kids and seniors.”

Manigque has mastered company statistics like the 300-plus partners that help them distribute through 900 sites in the two counties. But his knowledge of the organization and its impact is beyond professional.

“Best thing I like (about the work) is helping out the community and people where I live, and knowing I made a difference the same way SHFB made a difference in my family’s life,” he often reveals a personal connection.

Manigque arrived in California over a decade ago to reunite with his wife Joselyn, who had taken on a teaching job in the Golden State. He was armed with a Political Science degree from the University of the Philippines, but as a dependent, he was not authorized to work in the US, leaving them on a single income.

“We were in a very difficult situation then. My wife was the only one working on an H1-B visa. About half of her take-home pay went to rent. We had our daughter and we could not afford daycare or a babysitter, so I had to stay home and take care of her. Like most new immigrants, we did not know anything about benefits or services so we just made do with what we had,” he recalled.

Holidays were particularly challenging.

“I really do not remember celebrating our first Easter or Christmas in a big way. We were invited to other gatherings, but at our house I really do not remember celebrating our first Christmas here the way we did back in the Philippines. We had such a simple celebration. I think we just had some pancit, fruit salad, a small ham and a couple of ’round’ fruits” to invite prosperity in the oncoming year.

Provider instinct

“We had to avail (ourselves) of benefits and resources to help our economic situation,” said the then-new father. He was familiar with connecting folks in need to assistance having left behind in the Philippines his post as operations officer for an agency “providing loans to the agriculture sector, mostly farmers and fisher folk.”

From the outset, Manigque gravitated toward service. Volunteering, he realized, was rewarding in many ways. Had he not shared free time at the Daly City Library & Recreation Services, he said, he would not have met the Community Services coordinator who informed him of potential jobs when he would be eligible to work, along with benefits for newcomers.

The family turned to WIC or Women Infant Children, the special supplemental nutrition program providing federal grants to states for low-income pregnant women, infants and children up to 5 years old found to be at nutritional risk. One resource led to another, introducing the Manigques to a network of caring agencies in their adopted home county.

Manigque was willing to do whatever it took to provide for his wife and daughter.

“The WIC worker referred us to SHFB’s Family Harvest Program in Teglia Community Center in Daly City where I lined up to get food,” he recounts. “We were able to get in a low- income apartment building which also had a SHFB Produce Mobile distribution.”

A center volunteer asked him if he would consent to an interview by the food bank for its client stories, and he was happy to give testimony. Unexpectedly, the interviewee learned more about the organization and noted the “similarity of the kind of work I did in the Philippines, which was helping the underprivileged population.”

Manigque’s survival instincts kicked in big time.

“I looked into the available positions (at SHFB) knowing I would be able to help other families like me who also struggle in the community,” he says.

Manigque is living proof that a little help goes a long way, in fact all the way around.

A little help went a long way when Patrick, Joselyn and Angelica Manigque of Colma, California, started out over 11 years ago. CONTRIBUTED

“What I really want to achieve is to be able to help the whole community be more aware about what the food bank does, what our services are and that there is no shame in availing (ourselves) of these services. I often use my experience as an example when I talk to clients telling them that my employer was a big help to my family during our first years here in the US,” he makes nothing short of a declaration of loyalty and gratitude.

It took the Manigques three years to find help to start over, a situation the now-outreach worker notices as common among fellow Filipinos. Lack of information, however, is only one of the barriers they’ve had to overcome.

Barriers

“Like my family, most Filipino immigrants I talk to do not know much about the different services here in the US. They find it difficult navigating the system if they do find out about them, like medical, housing, and food.”

It gets worse: “They and a lot of our other clients as well, are also sometimes misinformed about benefits, I have talked to a lot of Filipino immigrants who would not avail (themselves) of benefits because of the wrong information, which they heard from friends, family members, even lawyers. Some also have a sense of pride when they find out that they have to line up for food and would refuse to sign up.”

Humility is a virtue that comes to play especially when the resource provider offers the assistance with respect and dignity.

Through his work, Manigque hopes to remove the stigma attached to getting any form of help, especially food. That’s why he always talks about his family’s early days as newcomers in his community presentations or to clients at government clinics in Daly City and San Mateo, where he passes out flyers and chats with people in the waiting areas or pre-screens for eligibility and actually helps with applications certain days of the week.

At the end of each day, he drives to a church in Daly City, where Joselyn, teaches by day before attending Early Childhood Education classes at night, and their daughter, Angelica, now 11, attends parochial school. This is where they will celebrate Easter, recall their new beginning, and give thanks for their blessings.