Bataan Memorial Death March: ‘Living history lesson’ in New Mexico desert

Brian Duffy (center), Commander-in-Chief of the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW), poses for a photo withFilVetREP leaders (from left) Arland Macasieb, Ben de Guzman, Mike Sembre and Sonny Busa. CONTRIBUTED

WHITE SANDS MISSILE RANGE, New Mexico — Filipinos and Filipino Americans – mostly descendants, relatives and supporters of World War II veterans – showed up here in large numbers on March 19, to honor the heroes of Bataan and Corregidor in what organizers describe as “a living history lesson.”

Along with more than 7,000 members of US military units, foreign armed forces, ROTC cadets, wounded warriors, veterans and family members, they came to reenact the ordeal suffered by 75,000 American and Filipino soldiers 75 years ago, when they marched for days in scorching heat through malaria-infested jungles in the Philippines following their surrender to Japanese Imperial forces.

Largely unknown and almost forgotten, the infamous 65-mile Bataan Death March claimed the lives of 9,000 Filipinos and 1,000 Americans. Many more died in prison camps.

Spirit of Bataan

But “the spirit of Bataan resides in each of us today,” said Col. Dave Brown, Garrison Commander of the White Sands Missile Range, where the Bataan Memorial Death March is held annually.

Family members and descendants of Bataan Death March survivors at the opening ceremonies include US Navy veteran Senior Chief Petty Officer Rey Cabacar (left) and Philip Baltazar, son of Purple Heart Awardee Jesse Baltazar, the last Filipino Bataan Death March Survivor who attended the memorial march before passing away last year. CONTRIBUTED

In his welcome remarks during the opening ceremony, Brown noted how “a remarkable group of World War II heroes encountered horrific combat conditions on quarter rations with little or no medical help, fought with outdated equipment with virtually no air power, and survived the atrocities of prisoner of war camps.”

Brown later asked all march participants to join him recite the cry of the Battling Bastards of Bataan: “No Mama, No Papa, No Uncle Sam, No Aunts, No Uncles, No Nephews, No Nieces, No Pills, No Planes, No Artillery Pieces, and Nobody Gives a Damn.”

After a brief pause, Brown exhorted: “Ladies and gentlemen, let our cry be known: We all give a damn!”

Brutal and painful

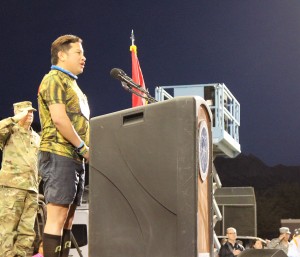

In his remarks, Maj. Gen. Antonio Taguba (Ret), chairman of the Filipino Veterans Recognition & Education Project (FilVetREP), recalled the “brutal, brutal, brutal” experience his father and his comrades endured in the hot jungles of the Bataan Peninsula, marching for 65 miles without food or water for days.

This year’s Bataan Memorial Death March has the largest number of participants, including Filipino and Filipino American family members and supporters of Filipino World War II veterans

Referring to the sandy and hilly terrain of White Sands and the 90-degree weather that marchers were about to face, Taguba warned that “it’s going to be painful out there, but not as painful” as the Bataan Death March.

“Let us be inspired by their service and sacrifice,” he urged the thousands of cheering participants massed in front of the stage at six o’clock Sunday morning. “Let’s do it for them, for their families, for us and for our country.”

Taguba’s father, Tomas B. Taguba, a U.S. Army Sergeant First Class in the 57th Infantry Regiment, was not among the eight Bataan Death March survivors who were seated on the front row that morning. He passed away in 2011. But Filipino World War II Veteran and Senior Chief Petty Officer Rey Cabacar, 89, of Fort Washington, Maryland was among them. His older brother Heren was a Bataan Death March survivor who died in 1981.

Cabacar was accompanied by her two daughters from Fort Washington, MD. – Vilma Megorden and Genevieve Thompson.

A poignant moment during the morning ceremony was the symbolic roll call of living survivors and veterans who have died since the last memorial march, followed by a bugler playing Taps. The Organ mountains overlooking the Missile Range echoed the names as they were called.

Among them was Purple Heart Awardee Jesse Baltazar of Falls Church, Virginia. A Bataan Death March survivor, he made a valiant effort to attend last year’s memorial march despite his ailing health. He passed away a few months later. He was buried in the Arlington National Cemetery.

FilVetREP Chairman Maj. Gen. Antonio Taguba calls on the 7,200 participants at the Bataan Memorial Death March “to be inspired by the service and sacrifice of the Bataan Death March survivors and our fallen heroes.” CONTRIBUTED

Baltazar’s son, Phillip, was seated among the families of survivors. Standing at attention while Taps was being played, he broke down in tears. He keeps returning to White Sands, he says, “because this place means so much to my dad. It reminded him of the brutality and savagery of the war, but also of the courage and nobility of his comrades who risked their lives for us.” Sixteen-year-old Ricky, Baltazar’s grandson who came with his dad to run the marathon for the second time, said he will always remember his grandpa’s advice: “Never give up, never surrender.”

Historic firsts

In commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the Bataan Death March, the singing of “Lupang Hinirang,” the Philippine National Anthem, was included in the program for the first time in the memorial march’s history. Filipino American marathoner and musical performer Jim Diego provided the vocal rendition. His great uncle, Ulrico Causing, was in the Bataan Death March.

The Philippine flag was also prominently displayed on stage beside the American flag, another significant first. “It gives me goosebumps just to see the Philippine flag and hear the Philippine national anthem sung,” said Christy Panis Poisot of Houston, Texas, a FilVetREP Regional Director. Her grandfather, Francisco Panis, was beaten badly during the Bataan Death March because of his rank as third lieutenant in the Philippine Army. He survived the prison camp and later rejoined Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s forces. He passed away in 2003.

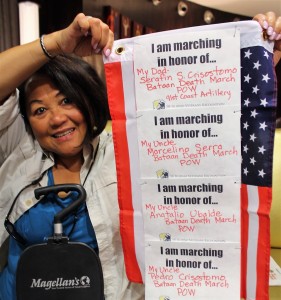

FilVetREP Regional Deputy Director Zenaida Crisostomo Slemp of Seattle, Washington, says she is marching for her dad and uncles, all Bataan Death March survivors. CONTRIBUTED

“Clearly, the memorial march is the nation’s largest gathering to commemorate a Philippine historical event, and the prominence given to Filipino American participation is a meaningful tribute to our Filipino soldiers’ role in the Pacific theater,” says FilVetREP Director Sonny Busa of Annandale, Va. Busa’s late father-in-law, Pantaleon Cawagas of San Narciso, Zambales, survived the Bataan Death March and later joined the guerrillas. This is the fourth time Busa and wife, Ceres, participated in this grueling trek.

March in the desert

Now in its 28th year, the marathon drew the largest number of participants from across the country and all over the world. It was also the hottest, with temperatures reaching 91 degrees at midday.

One team included Albanian, Filipino, German, Japanese and Korean master sergeants. Filipino American participants, estimated to be the largest this year, travelled from several states, including California, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Kentucky, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Texas, Virginia and Washington.

Since its inception in 1989, the Bataan Death March has been memorialized by a 26-mile march in the desert, covering paved roads and long trails of ankle-deep sand, and a 14-mile run for those who do not wish to run the full course.

A group of ROTC cadets in New Mexico started the marathon to honor members of the state’s National Guard who fought in Bataan and Corregidor. It grew over the years, from 200 to more than 6,000 marchers each year.

Filipino American marathoner and performer Jim Diego sings the Philippine National Anthem during the opening ceremonies, a first in the history of the Bataan Death March Memorial. CONTRIBUTED

Taguba started running in 2005, with his son, U.S. Army Capt. Sean Taguba, joining him in the last few years. Former Philippine Ambassador Jose L. Cuisia, Jr. attended in 2014, along with then Philippine Veterans Affairs Director Delfin Lorenzana, now Philippine Defense Secretary. Philippine Embassy officials and FilVetREP Board Members and Executive Committee officers are also regular participants.

Of the eight Bataan Death March survivors who came to White Sands this year, Retired U.S. Army Col. Ben Skardon, 99, was the only one who walked. This was his tenth time to do eight and a half miles.

The last person to reach the finish line was Kirk Bauer, an above-the- knee amputee who served in Afghanistan. He began the march at about 7:25 a.m. and completed 26.2 miles at around 10:00 p.m. This was the 68-year-old wounded warrior’s eighth march.

‘Duty to country’

The day before the march, participants availed of various educational programs, including display booths at the Exhibition Hall. The FilVetREP table was a meet-and-greet point and a resource for marchers and visitors. Among those who stopped by was Brian Duffy, Commander-in-Chief of the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW). VFW was the first national veterans advocacy group that endorsed FilVetREP’s Congressional Gold Medal campaign.

FilVetREP Regional Director Sonny Busa and FilVetREP Program Director Ben de Guzman made two presentations at the Post Theater, which included a screening of the documentary “Duty to Country,” a discussion of the 1946 Rescission Acts, the nationwide fight for veterans benefits, and the legislative campaign to secure Senate and House sponsors for the Congressional Gold Medal Award (CGM) bill.

FilVetREP also provided information about the National Registry and encouraged families of both surviving and deceased veterans to help identify CGM recipients. FilVetREP Regional Director Brig. Gen. Oscar Hillman explained the need to raise funds to cover the costs of CGM bronze replicas and FilVetREP’s education program.

UNIPro and FANHS Houston, Texas leaders (from left) Mark Sampelo, Trisha Morales, Rea Sampilo and Jenah Maravilla are among the FilVetREP volunteers who braved the hot sun and sands at the White Sands Missile Range in memory of their grandfathers. CONTRIBUTED

“I find it incredible that some marchers did not even know Filipinos were in the Bataan Death March,” Busa said. “

A hero’s story

On Saturday night, FilVetREP hosted a gala dinner at the Doubletree Hotel Sky Lounge, mainly to raise funds for the Congressional Gold Medal project. More than a hundred guests attended. Supporting organizations include the Filipino American National Historical Society, Filipino American Association of El Paso (FAAEP), National Federation of Filipino American Associations (NaFFAA), Bryan Ramos Law Firm, Pilipino American Unity for Progress, Inc., (UNIPro) and Tigua Indian Social Dance Group.

Speakers include FilVetREP Chairman Antonio Taguba and Philippine Consul General Angelito S. Cruz of the Philippine Consulate General in Los Angeles.

The evening’s highlight was a story shared by the keynote speaker, US Navy veteran Rey Cabacar. His older brother, Sgt. Heren Cabacar of San Narciso, Zambales, was a Bataan Death March survivor. After he was released following Japan’s surrender, he joined the US Army and was later deployed for combat in Korea.

His unit, however, suffered defeat and was forced to endure his second death march – the Tiger Death March. A POW for 32 months, he managed to survive by fishing and planting corn around the tents. A prisoner exchange led to his release. He later found himself assigned to Portsmouth, Virginia. In 1981, he was murdered on his way home in an apparent hold up.

“This brave soldier survived two wars, yet died in the streets of the country he fought for,” Cabacar said of his older brother. “His parting is a sweet sorrow and not in vain. He served this country’s flag well, with honor and dignity. The blood that ran in this soldier’s veins also runs in mine.”

‘Unforgettable experience’

Among the early risers Sunday morning is Zenaida Crisostomo Slemp of Seattle, Washington, a FilVetREP Regional Deputy Director. She says her first time joining the Bataan Memorial Death March has been “an emotional experience.” On the day of the march, she wrote down a list of names on small sheets of paper and pinned them to her shirt.

FilVetREP Program Director Ben de Guzman, FilVetREP Regional Director Christy Panis Poisot, UNIPro leader Jenah Maravilla and NaFFAA Exec. Director Jason Tengco are among the first at the starting line to march. CONTRIBUTED

“I’m marching for my dad, Serafin Salazar Crisostomo and my uncles Marcelino Serra, Anatalio Ubalde and Pedro Crisostomo,” she said. “They were all death march survivors and POWs. I’m glad we have an opportunity to educate the American people about what happened in Bataan. We must sustain our efforts to ensure that their story is never forgotten.”

Rea Sampilo, 26, President of UNIPRO Houston Chapter and Vice President of FANHS Houston Chapter, describes her first march as “an unforgettable experience. I marched for my grandpa, Benny De Leon Sampilo, a Filipino WWII veteran. It was definitely a challenge, but carrying his name on my back along with other veterans gave me the drive to complete the march. This was for them. Without their sacrifices and their service, we would not be here today.”