Anti-Asian hate: Why we must remember Vincent Chin this year

FILE PHOTO

Today is the day. Vincent Chin, 43 years after. As we remember the most iconic Asian American hate crime, not much has changed.

More than 53 percent of Asian American adults of all stripes say they’ve experienced a range of racial animus from a slur to physical violence, according to a new survey by Stop AAPI Hate.

Filipinos are in the mix of course. It’s not just Chinese who are victims, but everyone with a drop of Asian blood in America is in the crosshairs.

More significant is that it’s not race or ethnicity that is a trigger.

The victims are not older Asians, but younger ones. Take a look at the demos of the victims: ages 18-29 (72 percent), ages 30-44 (54 percent), ages 45-59 (46 percent) and ages 60 and older (44 percent).

The people who are more likely to be victimized in 2025 are young people born around 2000 who are more likely to ask, “Vincent Who?”

Why we must remember Vincent Chin in 2025

That’s why we must remember Chin in 2025. And not just the death day, June 23, 1982, when the family chose not to continue life support.

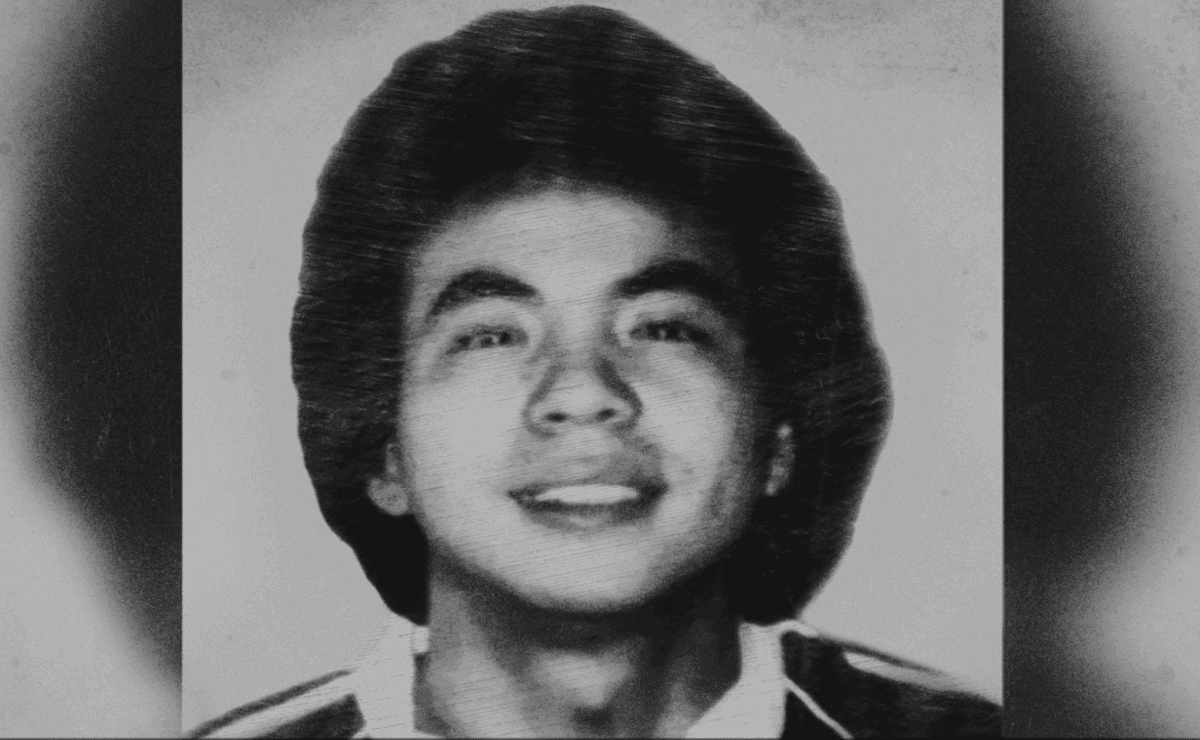

Vincent Chin | Photo from the Vincent Chin Institute

No, to do it right, we start thinking about the whole ordeal from the night on June 19th, at the strip club in Detroit for Chin’s bachelor party, and the fight that went from inside the club to out in the street.

When it was all broken up, it still wasn’t over. Ronald Ebens followed Chin to a suburban McDonalds parking lot. That’s where with a baseball bat, Ebens swung on Chin’s head.

That was the strike put Chin in a coma, but woke up Asian Americans.

As I’ve pointed out, the celebration of Juneteenth, the end of the protracted period of slavery in Texas and therefore the US, and the beginning of the Vincent Chin case is an historical coincidence that gives us an opportunity to recognize Black-Asian solidarity.

Delayed justice is our common ground.

June 19th was the day Chin’s killer Ronald Ebens, a white retired auto worker, struck Chin, then 27, with a baseball bat to the head. Chin remained in a coma until June 23rd, when he was taken off life support.

The path to justice for Chin will make your heart ache. Ebens spent no jail time for the murder and was allowed to plea bargain to second-degree murder. You want an example of abysmal justice? How does three years’ probation, a fine of $3,000, and $780 in court costs sound? For murder in the second degree.

The federal civil rights case was a logical response, and Ebens was convicted to 25 years in prison. But Ebens won an appeal for a new trial, which had a change of venue from Detroit to Cincinnati, and on May 2, 1987, Ebens was found not guilty on the federal charges.

That left the civil case, which was settled in court with Ebens ordered to pay $1.5 million. But since that time, Ebens has used the bankruptcy laws in Nevada (his new home) to avoid paying the estate a dime.

But here’s an important question for younger Asian Americans and newer immigrants to explore and understand. What were the 1980s like for Asian Americans? The times may have seemed modern. But in terms of American race history, the situation for Asian Americans 40 years ago was still the dark ages. Consider that US immigration laws changed only in 1965, leading slowly to our population growth.

A different time

On my “Emil Amok’s Takeout” podcast interview in 2017, I talked with writer Helen Zia, the executor of the Chin estate.

She told me that all these years later, what strikes her the most are the things people don’t bring up about the case.

The human stuff, like the late Lily Chin, Vincent’s adoptive mom. “She died feeling that if she hadn’t adopted him, he’d be alive,” Zia told me. “It’s so sad to me to think about it that way.”

But the human stuff also includes the opposition to the case within the community and the backlash that existed at the time.

“We had civil rights people who said, ‘We’ll support you because Vincent was Chinese and thought to be Japanese, but if he were Japanese, we won’t support because he would’ve deserved it,’ ” Zia said. “I said ‘What? You’re kidding?’ The Michigan ACLU and the Michigan National Lawyers Guild strongly opposed a civil rights investigation because they said Asian Americans are not protected by federal civil rights law. That was something we had to argue.”

Fortunately, the national offices of those legal groups prevailed and forced their state chapters to comply.

“Here were some of the most liberal activist attorneys saying Asian Americans shouldn’t be included under the civil rights law. Vincent was an immigrant. We had to establish he was a citizen, with the implication there might not have been a civil rights investigation if he had not been naturalized. All of this stuff…these were hurdles we had to overcome with major impacts today,” Zia told me.

“Can you imagine if the Reagan White House had followed the National Lawyers Guild’s Michigan chapter and the ACLU of Michigan and said, ‘Why should we look expansively at civil rights? We shouldn’t include immigrants and Asian Americans.’ And at that time, that would include Latinos too, because at that time if you were not black or white, what do you have to do with race? Those were the things people would say to us.”

Zia said a quick telling of the Chin case rarely discusses just how difficult it was to fight for justice. But she says those are the enduring lessons of the Vincent Chin case, because it has contributed to a modern sense of social justice for every American.

“Every immigrant, Latinos. Every American,” Zia said. “Hate crime protection laws now also include perceived gender and disability. It was the Vincent Chin case when we had to argue civil rights was more than black or white.”

Consider also the size of our community back then. Yeah, we’re about 26 million now, even closer to 30 million if you count mixed race Asians, but in 1980, the Asian American population was just 3.7 million nationwide.

“In the Vincent Chin case, people were incredibly reluctant to become involved,” Zia told me. “They had never gotten involved before. And I think that’s what gets lost in the retelling of the story. Exclusion didn’t end till about 1950, and so what that meant was Asian Americans of every kind, from Chinese to Filipinos, everybody, were pretty much totally disenfranchised till the mid-20th century.”

“So when Vincent Chin was killed 30 years later [in 1982], the communities had… I think of it as stunted growth. There weren’t people running for office. If there were, it was a minuscule number. There weren’t people standing up; we didn’t have advocacy organizations, except for AALDEF in New York and Asian Law Caucus in California, with no pan-Asian advocacy groups in between.”

A right to justice, and a community’s sense of empowerment, was a difficult thing to imagine for many Asian Americans. “Not only did we not have it,” Zia said, “People didn’t even recognize it was something we could have. The idea we all came together with the Vincent Chin case and sang ‘Kumbaya’ and took over and went to the Reagan White House and the Department of Justice and got all these things to happen…that’s a mythology. And I think it’s a disservice to the next generations to think this.”

These are the things worth pondering when meditating on Vincent Chin, 43 years later.

Every year it’s a benchmark for how far we’ve come as an ever-changing and dynamic community.

But now it’s just sad when you encounter people who want to move on, and ask if we really have to think about Vincent Chin again.

Well, yes, we do. Because now more than ever too many people are prone to ask, “Vincent Who?”

Take the time this Juneteenth weekend from the 19th to the official anniversary date to think about what happened in 1982, and where we are now.

Maybe you’ll feel the same call to action Zia and others felt 43 years ago to stand up for our right to exist free of hate and violence in this place we call home, America.

Emil Guillermo is an award-winning journalist, news analyst, stage monologuist and a poet laureate in Northern California. He writes for the Inquirer.net’s US Channel. He has written a weekly “Amok” column on Asian American issues since 1995. Find him on YouTube, patreon and substack.