Lying, passing, hiding — an undocumented immigrant’s life

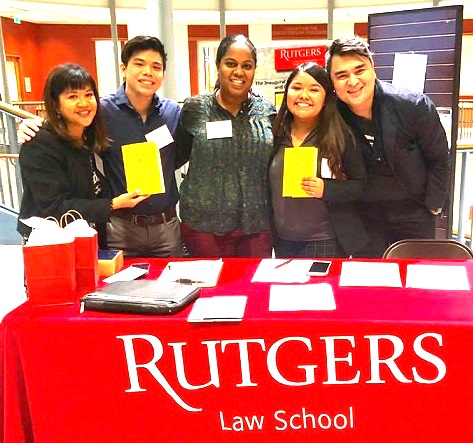

Jose Antonio Vargas (right) spoke before Rutgers students and faculty, lawyers and immigration advocates. ANNA MERCADO CLARK

NEW YORK — Pulitzer Award-winning journalist Jose Antonio Vargas remembers writing his first book –“not a memoir” – as he was being kicked out of his “Frazier-style” loft in downtown L.A. shortly after Donald Trump was elected president in 2016. The building manager warned him that Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) might show up in the building, and that it’s best for him to find a new place.

“I packed everything I owned, which is a lot, then I put everything in storage and I started writing this book,” he told the audience at Rutgers Law School’s Inaugural Distinguished Immigration and Citizenship Lecture. At the time he was writing it, he was moving from place to place looking for an apartment and traveling, and certain chapters in the book seemed like they were written in a hurry.

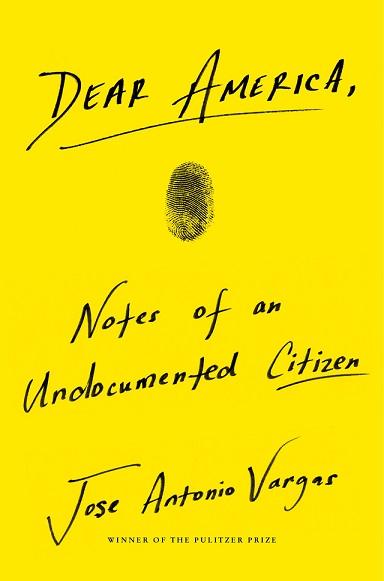

His original plan was to write about global migration and how some 250 million migrants around the world are resettling in countries that previously colonized them. Not too thrilled, his publisher asked him to write instead about the 20 “most painful” experiences in his life. And so, “Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen” was published by HarperCollins and is among Amazon’s national bestsellers. He chose the sunflower yellow color for the cover because “yellow is the color of Asians.” He has been on the road since Sept. 18. Rutgers in New Jersey was his 45th book event.

Vargas’ book, Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen.

His list of painful experiences he neatly filed in three sections: Lying; Passing; Hiding.

On learning he had a fake green card, Vargas’ life careened from one lie after another. He lied about his citizenship so he could get a job in major American newspapers, including the Washington Post where he earned a Pulitzer Award as part of the team that investigated the Virginia Tech mass shooting. He lied about his family, his not having a car, the reason he didn’t want to go to Baghdad to become a foreign correspondent for the Post.

“I lied about being a U.S. citizen because that’s the only way I could get a job,” he said. “Lawyers said to me the fact that I lied about being a citizen when I’m not may be the reason why I might never be a citizen.” Perjury is a major criminal offense.

Passing became another way to perpetuate his lies. The first thing he did to pass as an American was to get rid of his Tagalog accent. He began to talk the way Americans talked, eliciting comments like, “You sound so Californian!”

“Yeah, I totally passed,” he said.

Hiding. After 911, it became even more difficult for him to enter government offices because all he had was a bogus driver’s license issued in Oregon. When government sources would invite him to their offices, he would suggest meeting instead at a coffee shop nearby.

Vargas said a pardon from the President, which is highly unlikely, is one of the ways he could have his status adjusted. Another possibility that could “save” him is a private bill from his lawmaker. He dismissed that idea, saying, “What will that say to the 11 million undocumented in this country, that I am more worthy than they are? Why, because I was with the Washington Post?”

Immigration reform legislation is another solution, but he is not confident a law would pass under the current political climate. Self-deportation with the option to return after a 10-year ban is the fourth option. The return to the U.S. is not guaranteed, he said. He urged the Americans in the audience to value their citizenship and not take it for granted.

Rutgers Professor of Law Rose Cuizon Villazor said Vargas became the first speaker at the Inaugural Distinguished Immigration and Citizenship lecture because of “his indefatigable work towards advancing immigrants’ rights.”

“When we were looking for someone who has advocated passionately for immigrants’ rights on a national level and has helped to change the conversation about immigration law, we easily thought of Jose Antonio Vargas,” she said.