Historical site honors Filipinos displayed as ‘savages’ at 1904 World’s Fair

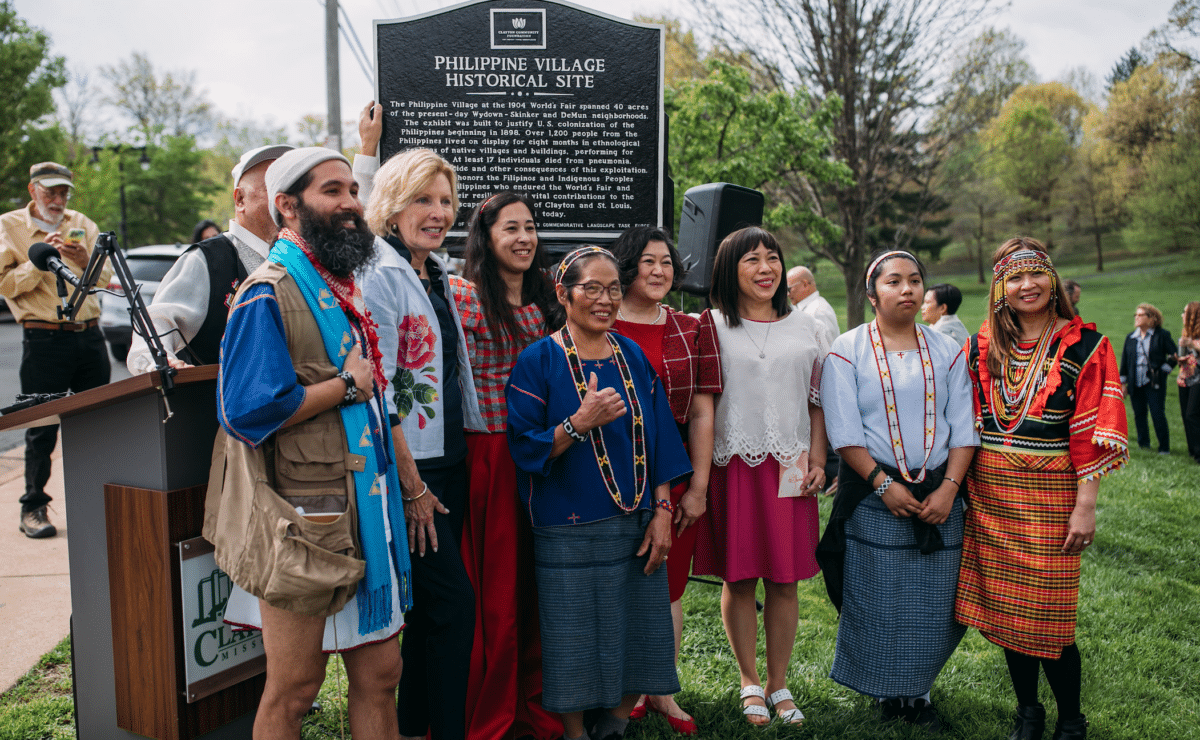

Janna Añonuevo Langholz (3rd from left) – artist, historian and caretaker of the Philippine Village Historical Site – and Clayton Mayor Michelle Harris (2nd from left) with members of the Filipino American community during the unveiling of the permanent marker. Photo by Jenna Grissom/J Elizabeth Photography

CLAYTON, Mo. – The Mayor’s Commemorative Landscape Task Force, in partnership with the Clayton Community Foundation, has installed a permanent historical marker to honor the Filipinos and Indigenous Peoples from the Philippines who endured brutality and exploitation at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri.

The marker – unveiled on April 18, 2025 – acknowledges the resilience and vital contributions of Filipinos to the cultural fabric of Clayton and St. Louis, both historically and today.

Developed in collaboration with the Philippine Village Historical Site community and key stakeholders – including Indigenous tribe representatives, Filipino scholars, Filipino American community members and local educational institutions – the marker aims to preserve this important chapter of history.

Indigenous Peoples endured exploitation at 1904 World’s Fair

Located at Concordia Park in Clayton, the site spans 40 acres now occupied by the Wydown-Skinker and DeMun neighborhoods, adjacent to Forest Park.

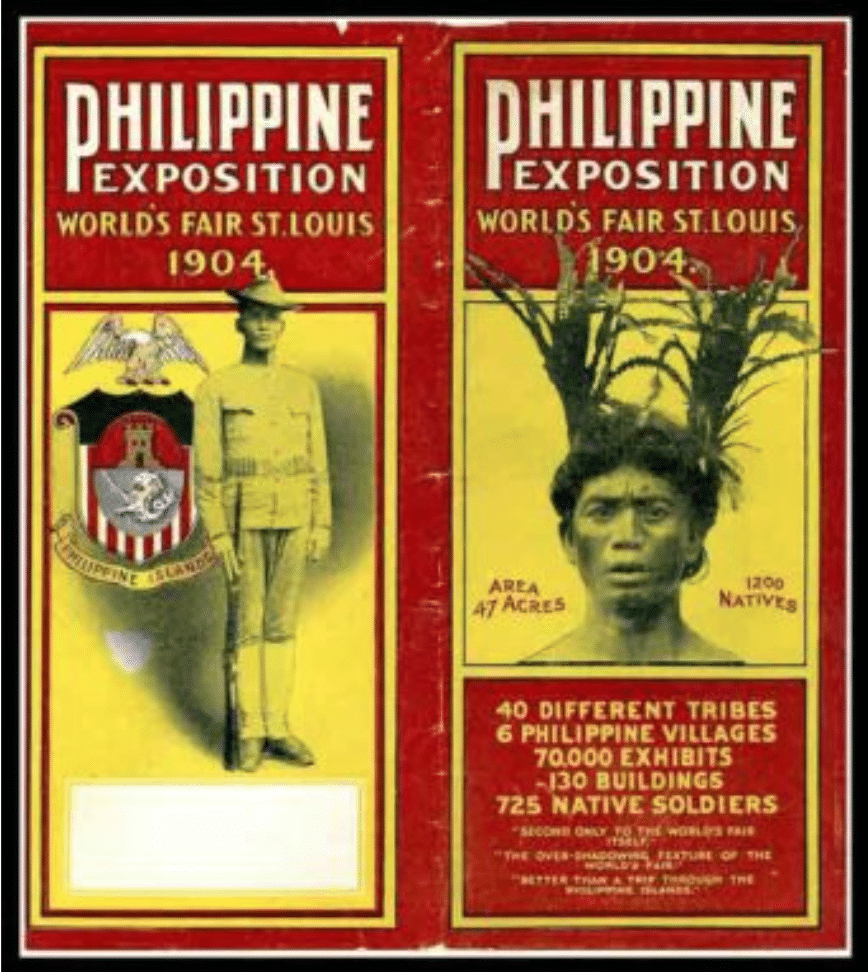

The Philippine Village at the 1904 World’s Fair – also known as the Louisiana Purchase Exposition – was a propaganda-driven exhibit intended to justify US colonization of the Philippines.

Over 1,200 Filipinos from various regions, mostly from the Igorot tribe of Northern Luzon, were brought to St. Louis, where they were forced to live in recreated villages within the exhibition site for eight months, enduring exploitation and public scrutiny.

You may like: Smithsonian to repatriate remains of Filipinos who were exhibited at 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair

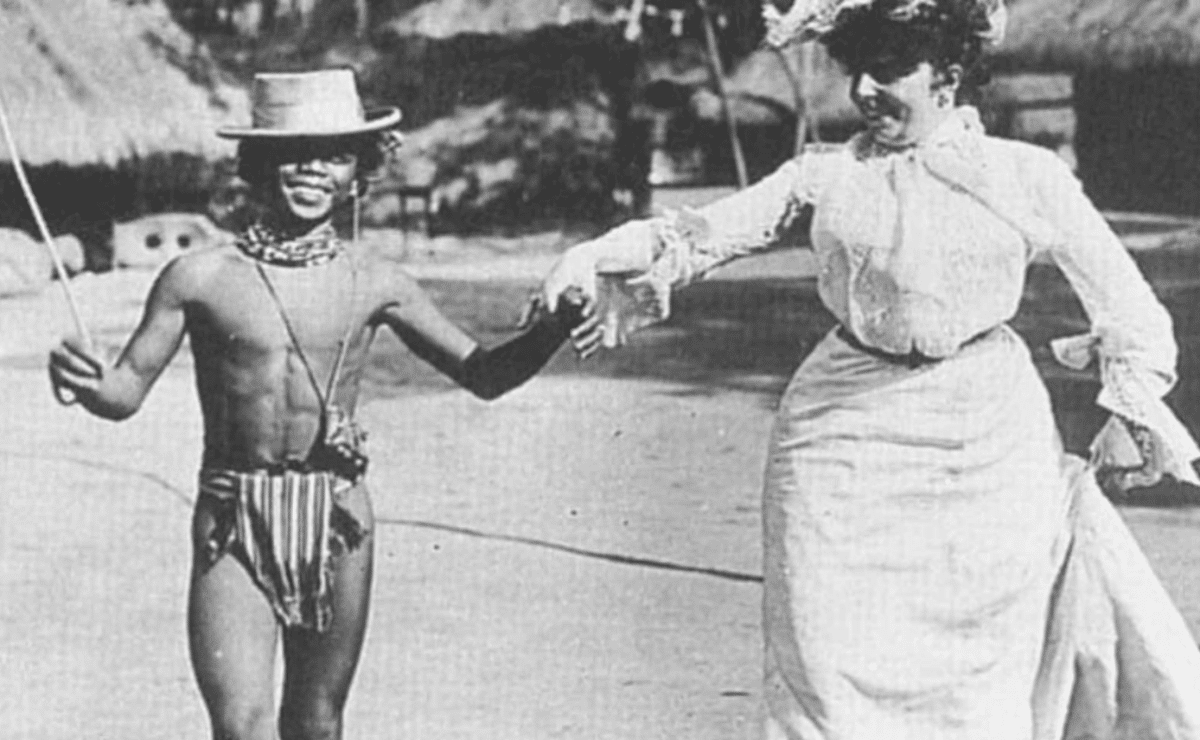

A 1904 World’s Fair-goer teaches a Filipino ‘exhibit’ the cakewalk dance. FILE PHOTO

1904 World’s Fair program | FILE PHOTO

Filipinos depicted as ‘savages’

They often wore traditional attire unfit for the extreme weather in Missouri, and were depicted by the fair’s organizers as “savages” or primitive.” At least 17 Filipinos died from pneumonia, malnutrition or suicide.

“For decades, this painful chapter of history was erased from public memory,” said Clayton Mayor Michelle Harris. “With this marker, we acknowledge that history and ensure the stories of those affected are recognized and remembered.”

Clayton Mayor Michelle Harris addresses the crowd during the unveiling of the permanent marker at Philippine Historical Village Site. Photo by Jenna Grissom/J Elizabeth Photography

Mayor Michelle Harris (left) and Janna Langholz unveil the permanent marker honoring Filipinos at the Philippine Historical Village. Photo by Jenna Grissom/J Elizabeth Photography

Janna Añonuevo Langholz, a Filipino American and caretaker of the Philippine Village Historical Site, has dedicated the past several years of her life to memorializing Filipinos, particularly Indigenous individuals, who died before and during the 1904 World’s Fair.

Janna Añonuevo Langholz, artist, historian and caretaker of the Philippine Village Historical Site, speaks to attendees during the unveiling of the permanent marker to honor Filipinos who endured exploitation during the 1904 World’s Fair. Looking on is Clayton Mayor Michelle Harris. Photo by Jenna Grissom/J Elizabeth Photography

“By portraying native customs as primitive, the US government and fair organizers sought to prove Filipinos were unfit for self-rule,” Langholz writes on the site’s website. “Meanwhile, those in the Philippine Village did their best to live under public scrutiny – falling in love, getting married, giving birth and dying – on display for the American public.”

1904 World’s Fair portrayed Filipinos as ‘unfit for self-rule’

As an artist and the project’s driving force in installing a permanent marker to honor the Filipinos who lived and died during the 1904 Fair, Langholz firmly believes in the power of art to create meaningful change, “especially in addressing historical erasure.”

“I’ve always approached this project as an artist working with the community and public space,” she said. “Being an artist has allowed me to take on unexpected roles, such as engaging with local government,” she said.

Mayor Harris and Langholz with community members and project supporters. Photo by Jenna Grissom/J Elizabeth Photography

Langholz embarked on this journey in 2021, during the pandemic lockdown, when she learned about “Maura,” one of the Filipinos brought to St. Louis from the Philippines, to participate in the 1904 World’s Fair. Maura died of pneumonia the day after the Fair opened.

“I can’t explain why her death, so long ago, affected me so much, but it became my goal to honor her,” Langholz said.

Langholz’s initial idea to plant a tree in Maura’s honor at the former site of the Philippine Village expanded into a project to honor all 1,200 people from the village. “I learned about Maura’s death through a coincidence – on April 20, 2021, an unusual spring snow in St. Louis caught my attention,” she explained. “I later found out that Maura had died from pneumonia the day after the snowstorm.”

As part of her research, Langholz explored archived newspapers from 1904, focusing on the days surrounding the unusual snow.

Growing up in the “ruins” of the Philippine Village site made the historical research more vivid for her. She pieced together the stories of the people involved, including Maura, a young Kankanaey woman, listed as 18 years of age but whom Langholz believes would have probably been in her mid-to-late 20s. Langholz explained, “American officials often underestimated Filipinos’ ages, and I suspect they did so with Maura as well.”

Maura’s brains taken for research by the Smithsonian

Maura, who had two children, traveled to St. Louis with her family. She fell ill with pneumonia on April 11 and passed away on April 21, 1904. Her final wish was to be buried in her hometown of Suyoc in the Cordillera mountains. However, her body was displayed as an attraction at the fair, alongside two young Igorot men who had also died. Fairgoers viewed their corpses over several months.

“It was one of the most horrific things I’ve ever learned,” Langholz said. She later discovered that Maura was one of four individuals whose brains were taken for research by the Smithsonian. The remains were incinerated due to poor preservation.

Four years ago, Langholz designed and created a temporary marker for the site. She began carrying this marker around her neighborhood daily, determined to ensure that Maura received proper recognition.

Community members joined her effort by helping to carry the temporary sign, attending events and donating money to install permanent grave markers at the cemetery.

Langholz expressed gratitude for the community’s support and for the strong turnout of fellow Filipino Americans at the marker’s unveiling on April 18, calling it “a deeply emotional experience.”

“The years of work leading to the marker’s installation were challenging but worth it,” she said. “The unveiling gives closure to my efforts to honor Maura and the 1,200 Filipinos who endured exploitation during the 1904 World’s Fair.”

Langholz concluded, “I can now rest, knowing there is a permanent historical marker. I hope it honors the strength and determination of Filipinos and Indigenous Peoples – both past and present.”