December 1898: Spanish-American War formally over

On December 10, 1898, representatives from the United States and Spain signed the Treaty of Paris. The treaty negotiations had commenced on October 1, 1898. The treaty concluded six months of hostilities between the new and brash imperial power, the United States, and the decrepit imperialist, Spain.

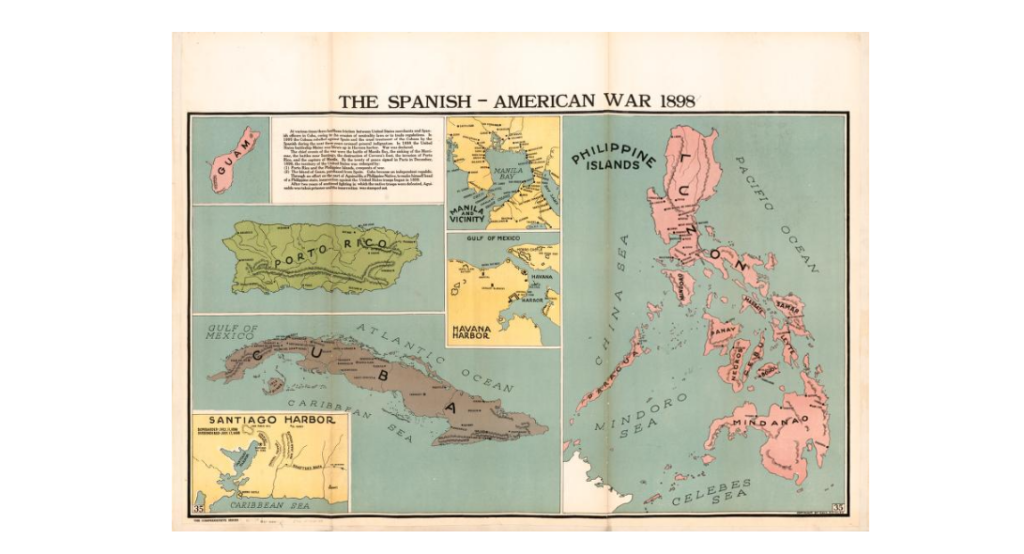

Noticeably, there were groups who were missing from the signing of the treaty. The treaty greatly affected the lives of Cubans, Puerto Ricans, Guamanians and Filipinos, but they were excluded and basically irrelevant to the proceedings. These four groups comprised Articles I, II, and III of the treaty. The year 1898 was probably the height of unbridled colonialism, so the “natives” really did not matter.

Initially, the Spanish delegation at Paris objected to the Americans gaining possession of the Philippines. Spain argued that the Battle of Manila occurred on August 13, 1898, which was the day after the signing of the armistice between Spain and the United States. Once President William McKinley of the United States decisively chose to annex the entire Philippine Islands, Spain’s leverage diminished.

Philippines bought for $20 million

The best option in the treaty for Spain regarding the loss of the Philippines was compensation. Spain claimed that it had made significant public works improvements in the Philippines over the years. Spain was able to negotiate for 20 million dollars, or approximately 545 million in today’s money.

Article X of the Treaty of Paris was interesting. The article stated that the “inhabitants” of the newly acquired American possessions were entitled to free exercise of religion. Essentially, the Filipinos, who were predominantly Roman Catholic, could not be compelled to convert to Protestantism. The article did not prohibit Protestant missionaries from religious conversion in the Philippines.

Under the American constitution, treaties with foreign nation-states must be ratified by the United States Senate. The Treaty of Paris was not official until Senate approval. In the Senate, there was substantial opposition to American annexation of the Philippines. A vocal group of anti-imperialist senators thought that American colonialism would destroy the American Republic.

‘Benevolent Assimilation’

On December 21, 1898, President William McKinley issued the “Benevolent Assimilation.” The document stated that the United States had sovereignty over the Philippines and Filipinos in government control and military rule. If needed, the military sovereignty could be imposed by force if the Filipinos do not comply.

President William McKinley and other top government officials naively thought that the “Benevolent Assimilation” would be widely and positively accepted by Filipinos. The president must have been ignorant or dismissive of the Malolos Republic proceedings and the composing of the Philippine Constitution.

The president surely had to be aware of the informal alliance between the United States and Emilio Aguinaldo in defeating the Spanish. He had to know about the tension between the Filipino and American soldiers since the Filipinos were excluded from the Battle of Manila on August 13, 1898. The president’s military advisors must have informed him about Filipino concern and reaction to the arrival in Manila Bay of more and more American soldiers.

Considering the McKinley Administration’s inexperience and unfamiliarity of the situation in the Philippines, the “Benevolent Assimilation” had the potential to be a powder keg in Manila and the surrounding areas. General Elwell Otis, the military-governor, realized the precarious nature of the document. He chose to suppress the posting of the document. He did not release the “Benevolent Assimilation” until January 4, 1899.

The average American soldier in Manila was no longer hearing rumors of a speedy departure home to the United States. The soldiers were constantly hearing rumors of Filipino rebel attacks. During some days in December 1898, they were ordered to be close to their quarters. Both the American and Filipino soldiers were expanding their entrenchments around Manila which became closer and closer to each other.

Holiday festivities in 1898

The American soldiers did enjoy December’s change of temperature. Since they had arrived in Manila Bay during June and July, the days and nights had been sultry. The December nights were getting chilly, and they slept comfortably with their warm blankets. The cool nights reminded them of fall nights back home.

The Filipinos’ Christmas celebration impressed and intrigued the American soldiers. Manila had sections with spectacular illuminations and fireworks. On Christmas Day, the church bells rang loudly throughout Manila. During a pleasant Christmas Day in 1898, the American soldiers were able to open their Christmas presents from home.

As the last day of 1898 came to a close, the American soldiers were once again fascinated and attracted by the Filipino preparations for New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day. On New Year’s Eve, American military bands filled the streets and joined the Filipino and American celebrants.

Based on the spirit of the holiday season in December 1898, it was hard to believe that Filipino and American soldiers would be shooting each other in only five weeks.

Dennis Edward Flake is the author of three books on Philippine-American history. He is a public historian and a former seasonal park ranger for the National Park Service at the Eisenhower National Historic Site in Gettysburg, PA. You can reach him at: flakedennis@gmail.com.