ATOMIC ARCHIVE

MANILA—Christopher Nolan’s three-hour biopic on the American theoretical physicist Robert Oppenheimer, titled simply Oppenheimer, portrays the brilliant scientist, regarded as the “father of the A-Bomb,” as supremely confident in his genius but at the same time aware—an awareness that grows exponentially –of the almost unimaginable horrors that nuclear weaponry can unleash on the world as we know it.

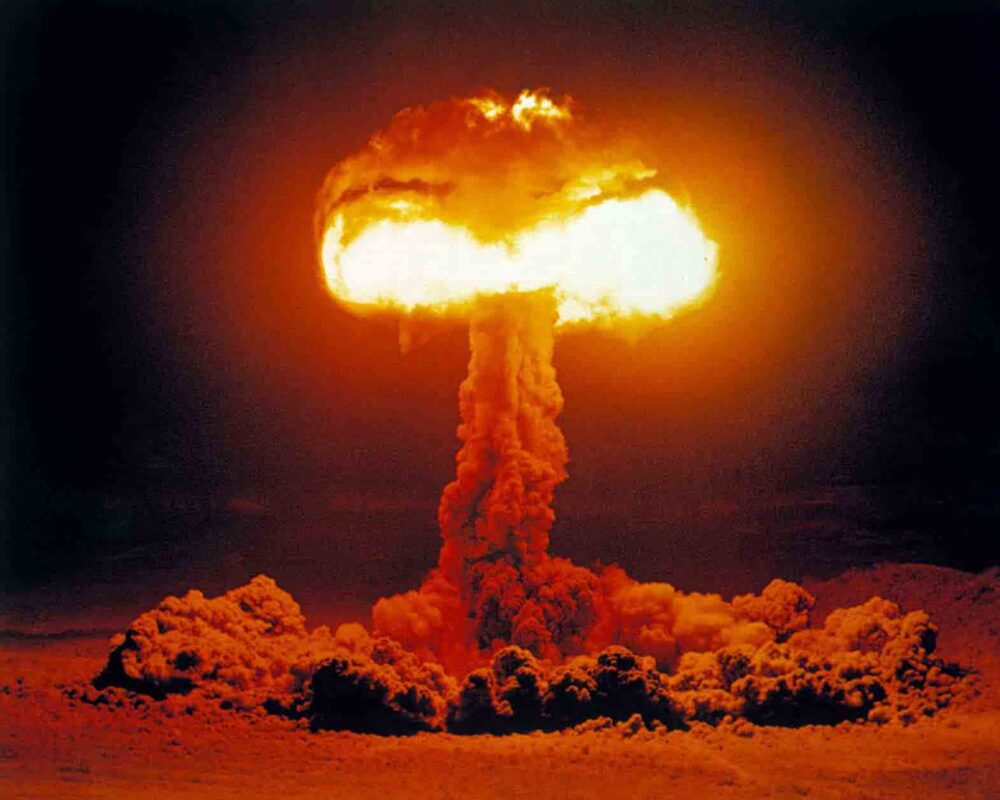

Based on the book, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, the film largely concentrates on Oppenheimer’s pivotal role as the director of the federally funded Manhattan Project—based in Los Alamos, New Mexico—whose aim was to build a nuclear weapon to use against both the Nazis and the Japanese during World War II. The Trinity nuclear test, as it was named, was successful, and it is in the build-up to that fateful explosion that the film is most compelling. By then, Nazi Germany had surrendered, leaving Imperial Japan as the sole target in the Pacific theater.

And indeed on August 6 and 9, 1945, the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were leveled by Little Boy and Fat Man, code names respectively for the bombs that killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, mostly civilians. The bombings are so far the only instances that nuclear weapons have been used in an armed conflict. Japan did yield unconditionally to the Allies on August 15, six days after Nagasaki, with Tokyo signing the declaration of surrender on 2 September.

A reader of the Bhagavad Gita, in its original Sanskrit, Oppie, as his friends called him, recalls the words of Vishnu following the Trinity test: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” The acting, with a sterling cast, is uniformly excellent, with Cillian Murphy in the title role, Matt Damon as his military minder, Robert Downey Jr as his antagonist, and Emily Blunt as his wife. I understand Christopher Nolan’s focus as being on what drove Oppenheimer, both as a man and a scientist, in his role as the father of the A-bomb, and later, as an advocate for arms control once he and other scientists of the Manhattan Project—20thcentury versions of Prometheus—realize the enormity, the consequences, of what they have wrought.

In the postwar era of the Red Scare, McCarthyite paranoia that imagined Communists hiding in plain sight, and a strong undercurrent of antisemitism, Oppenheimer is targeted because of his left-wing views, and his association with members of the Communist Party of the USA. The Hoover-directed FBI kept a file on him, and he was denied his security clearance—lifted only last year, more than fifty years after his death in 1967.

The film seeks psychological insight rather than physical delineation. Hence, as some reviews have it, the film deliberately excludes documentary footage of the massive tragedies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But would the film have lost anything had it expanded the historical context by showing the horrors of those bombings? Or put another way, would the film have gained something deeper and more gut wrenching by including that footage, the physical illuminating in more ways than one, the ensuing psychological trauma—and dilemma?

And what about the half million human beings who lived within a 150-mile radius of the New Mexico detonation—some only 12 miles away? That stretch is almost always depicted as desolate and practically empty of human habitation—an eerie echo of white settlers depicting the West as empty space, to be claimed willy nilly. Empty perhaps of white human habitation, but not of Native Americans and Latinos. They and all those who lived downwind of the test were undeniably the first victims of nuclear fallout. That nuclear fallout has plagued not just those who lived through that explosion but those born after, even to this day: cancer and heart disease are among the many serious health problems residents face, exacerbated by more nuclear tests in Nevada in the 1950s.

Those exposed to the Trinity and other nuclear test sites have identified themselves as “downwinders,” relating their health problems to the government’s nuclear program. To compensate those affected by the Nevada tests, the United States enacted the 1990 Radiation Exposure Compensation act but neither compensation nor apology is offered those affected by the Trinity test, whose exposure rates are, according to a 2010 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “10,000 times higher than currently allowed.”

Nothing on this in Nolan’s film, which may be aesthetically pleasing but conveniently skirts the morally complex issue of depicting human suffering. Might this have been a desire to avoid a partisan right-wing assault were the barbaric effects on Japanese bodies shown?

Less may be more, but this is one time when less is less, and more would have been more.

Copyright L.H. Francia 2023