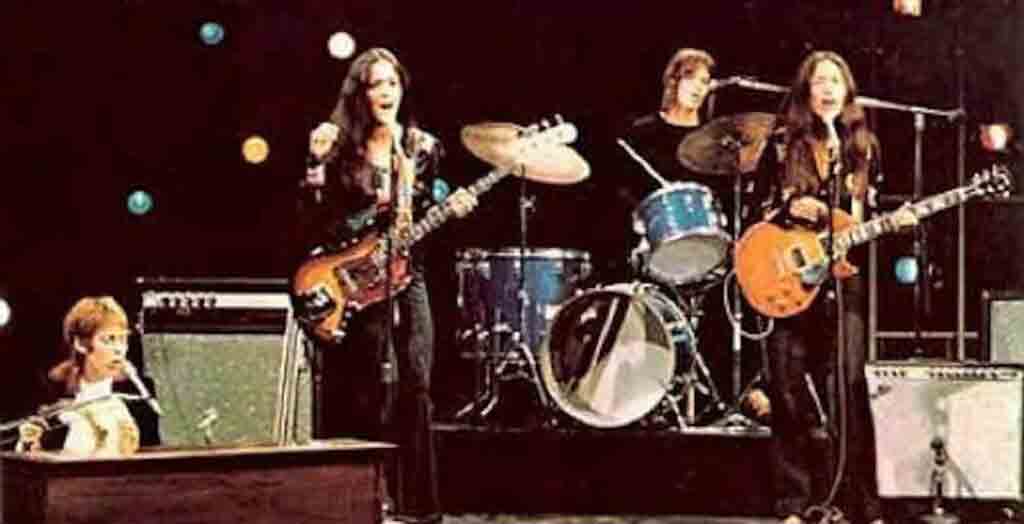

Fanny, led by Fil-Am sisters, was the highly regarded first all-female rock band that has been largely ignored by history. INQUIRER FILE

NEW YORK—It isn’t just a question of invisibility but often also of a deliberate shunning, of adding insult to injury. Probably one of the most egregious examples has to do, again, with war, not of 1899 but of World War II. Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor and invasion and subsequent occupation of the Commonwealth of the Philippines in December 1941 resulted in the United States joining the war.

Even before the outbreak of the Pacific War, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had federalized the armed forces in the archipelago, with General Douglas MacArthur appointed head of the United States Armed Forces in the Far East (USAFFE). More than 200,000 Filipinos—legally American nationals—fought to drive out the invaders and defend the United States, and thus were entitled to all the benefits normally given to veterans who had served the US.

You may also like: Invisible Country: Hiding in Plain Sight, Part I

The estimated cost of these benefits to Filipino veterans was $3 billion ($49 billion today), a cost that proved to be a bridge too far for the US Congress. Opting for savings over saving veterans’ lives through medical care, pensions, and other much needed services—much like the emphasis today’s Republican Party favors, though in 1946 it was two Democratic senators pushing for the budget cut—Congress passed the Rescission Act of 1946. What this bill did was to annul benefits to Filipino troops for putting their lives on the line for both the Commonwealth and the United States. As a sop, a single $200 million direct payment to the Philippine government replaced the estimated $3 billion in benefits. Not surprisingly, the act was denounced by the Philippine Commonwealth, with its president, Sergio Osmena, pointing out that the $200 million was “inadequate for the payment of the benefits it intends to confer.” There were sixty-six countries that had allied themselves with the United States during the war, but only Filipino servicemen were denied their rightful military benefits.

Corollary to this shameful legislative backstabbing has been the relative lack of acknowledgement of the wartime destruction of Intramuros, the ancient center of Manila, principally by US artillery, during the battle to liberate the city from the Japanese. Much of the walled citadel was reduced to rubble, and a great number of its mostly Filipino residents killed. This is not to downplay the horrific brutality the Japanese army inflicted on the populace outside Intramuros. Unlike Kyoto, which the US spared from bombing due to that city having been Japan’s ancient capital and a veritable treasure house of Japanese art and culture, Intramuros, despite its being the centuries-old heart of Manila, failed to be accorded the same respect, and this, in spite of the United States having occupied the country since 1898. In effect, the United States showed more consideration towards its enemy than towards an ally that had suffered tremendously on its behalf. Manila is considered, after Warsaw, the most devastated city of the war—excluding the A-bombed cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

It might be that the weight of a history still heavily saddled with colonialist overlays—Spanish, American, Japanese—results in an aversion, a shamefaced one at that, of many Filipinos to their own context with an almost knee-jerk openness to Western cultures that all too often results in their own culture being a desaparecido. Complicit, we disappear ourselves, and thus share some of the blame for our invisibility. As Cassius says to Brutus, “The fault, dear Brutus, lies not in our stars but in ourselves that we are underlings.”

No surprise then that rather than deal with this tangled, complex history, or should I say histories, finding themselves in intercultural and interracial relationships where the significant other is white, so many opt to slough off their identity like so much dead skin to take on that of the partner. Inevitably, this process of conversion comes at great psychic cost, measured proportionally by the fervor with which the new convert proselytizes on behalf of the assumed identity cum culture—the louder, the more intense, the deeper the hidden anguish and the contradictions. The brown or black cheerleader for white supremacy, of which there is a large number, in the end what is he or she but a pitiable form of self-loathing?

Copyright L.H. Francia 2023