Unearthing a Little-Known History: Filipino footprints in Washington, DC

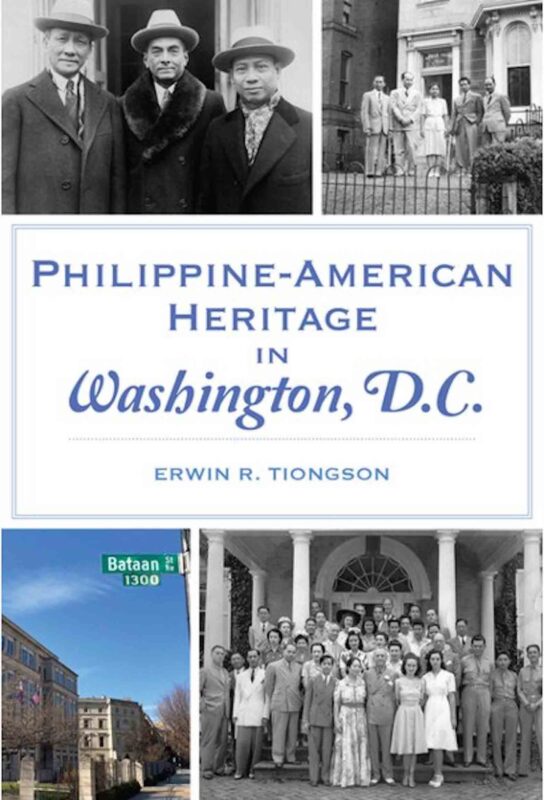

Erwin R. Tiongson has written a fascinating history of the close and not so-close encounters between citizens from the two countries in Philippine-American Heritage in Washington, D.C.

NEW YORK—Having moved to the nation’s capital after World War II, Josefina Guerrero lived a life of anonymity in the nation’s capital. A member of the local parish of St. Stephen Martyr Catholic Church in the Foggy Bottom district, she worked as an usher for the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and walked there from her nearby apartment, dressed simply in a black skirt and long white blouse. At the Center, she was known as “Joey Leumax, usher, volunteer,” according to her biographer Ben Montgomery in his Leper Spy: The Story of an Unlikely Hero of World War II.

Not many knew of her daring exploits during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines. Having been afflicted with leprosy as a young woman, she made sure that Japanese soldiers would see her condition, and thus let her move freely, enabling her to relay invaluable information from Filipino guerrillas to American troops, and saving countless lives. Her bravery led to her being awarded the Medal of Freedom by President Harry Truman. She passed away in 1996, her obituary simply stating “Joey Guerrero Leumax, Kennedy Center usher.”

Guerrero’s story (or fittingly the story of a warrior, which is the English translation of the Spanish guerrero) is one of the more interesting facts contained in Erwin R. Tiongson’s Philippine-American Heritage in Washington, D.C. (Charleston, SC: The History Press). A professor at Georgetown University’s Walsh School of Foreign Service, where he teaches economics, Tiongson has written a fascinating history of the close and not so-close encounters between citizens from the two countries, covering roughly a century’s worth of interaction in this city by the Potomac.

One can read about the unsuccessful visit in early 1899 of the painter Juan Luna and the diplomat Felipe Agoncillo, as representatives of the Aguinaldo government to try and convince the US Senate to desist from ratifying the 1898 Treaty of Paris —negotiations over which no representative of the Aguinaldo government was allowed to attend—wherein in the aftermath of the 1898 Spanish-American War, for $20 million, a defeated Spain handed over the Philippines to a triumphant United States, eager to join the ranks of empire builders. Despite repeated written entreaties, Luna and Agoncillo were unable to bend any senator’s sympathetic ear. A few days into their stay, on February 4, 1899, a shot by a Pvt. William Grayson of the Nebraska Volunteers in what is now the Sta. Mesa/San Juan district, ignited the Philippine-American War. The US Senate quickly ratified the treaty, and Luna and Agoncillo quietly exited the capital, to avoid arrest.

Among other fascinating facts:

- Juan Arellano, the preeminent pre-World War II architect behind such landmarks as the Art Deco Metropolitan Theater (renovated in 2021), Manila’s central post office, and Jones Bridge, had in 1927 exhibited his watercolors at the Arts Club of Washington. Twenty years earlier, Arellano had been part of the 1907 Jamestown Fair, where, similar to the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, costumed as a “wild man” he was part of a dehumanizing and racist exhibition, ostensibly to display the beneficent results, the mission civilisatrice, of colonialism.

- Sofia de Veyra, spouse of Jaime de Veyra, Philippine resident commissioner (1917-1923) and nonvoting member of the US Congress, seemed to have made more of a mark than Jaime. Ultrasmart, sophisticated, fluent in English, she traveled the country, educating her American audiences about the Philippines, opening up, according to one impressed lawmaker’s wife, “my provincial eyes.”

- Writers and artists who went on to be widely published and acclaimed spent time in DC. In 1919 a young Guillermo Tolentino gifted President Woodrow Wilson Pax, a small sculpture of a young woman and her child representing peace. Tolentino went to have a storied career, teaching at the University of the Philippines and being named National Artist by the Philippine government in 1973. During World War II fiction writer Bienvenido Santos and poet Jose Garcia Villa worked out of the Old Philippine Chancery for the Philippine government in exile. The latter by then had had a collection of short stories, Footnote to Youth, and his first volume of poetry published in the US, Have Come, Am Here.

I am surprised Tiongson doesn’t include the scandalous affair Douglas MacArthur had with a teenaged Filipina mestiza movie starlet, Isabel “Dimples” Rosario Cooper, began in Manila in 1930, and continued in Washington where MacArthur was recalled to be the chief of staff of the US Army. He ensconced Dimples at Hotel Chastelton on 16th Street. L’affaire Dimples was all hush-hush, but due to a libel suit brought by the general against two Washington journalists for an article critical of his mishandling of World War I veterans protesting their lack of benefits, the journalists found out about Dimples, and threatened to blow MacArthur’s cover if he persisted. Suit withdrawn, as well as MacArthur’s role as sugar daddy.

It didn’t end well for Dimples. Rather than returning to the islands, she stayed and wound up as an actress in Hollywood, cast in minor, even uncredited, stereotypical roles as an exotic Asian beauty. Unable to break the glass ceiling and depressed, she took her own life in 1960.

By veering away from academic abstractions, exploring different parts of the city, and by placing his- and herstories front and center, Tiongson provides valuable perspective and historical context to that segment of the Philippine diaspora, past and present, for whom Washington, DC loomed large, and continues to do so.

Copyright L.H. Francia 2023