Filipino and Cuban insurrectos on eve of Spanish-American War

Filipino insurgents against Spanish rule.

By 1821, the once powerful and vigorous Spanish Empire was close to extinction. The country that had controlled most of North, Central and South America was reduced to holding two islands in the Caribbean and a few islands in the Pacific.

Based on this dramatic shrinking of its empire, Spain should have learned from its colonial mistakes. It should have treated its remaining colonies with enlightened policies. This was not the case. There were very brief periods of enlightened rule, but most of its time, fear of losing its few residual colonies led to brutal and barbaric rule.

Cuba in the Caribbean and the Philippines Islands in Asia were the largest and most important of the few remaining Spanish colonies. Throughout the 19th century, the two colonies had advocated for basic reforms. They would have preferred independence from Spain, but reasonable reforms would have satisfied them. Eventually, proposed reforms for the Philippines and Cuba were looked upon by the Spanish as radical and revolutionary. To Spain, even the hint of reform was seen as an incipient revolution.

By the 1860s in Cuba and the 1870s in the Philippines, the lack of reforms led to armed revolutionary movements. These independence movements would ebb and flow overtime, but they were unable to defeat Spain rule.

There was dramatic change for the insurrectos once the United States declared war on Spain in April 1898. The intervention of the United States during the Spanish-American War finally gave the insurrectos the needed backing and support to defeat the Spanish.

The Philippine insurrectos on the eve of the Spanish-American War had been established on July 7, 1892. The Katipunan was very secretive and modeled after Masonic lodges and rites. A blood oath was required for membership. The Katipunan planned for an armed revolution against the unyielding brutality of Spanish colonialism in the Philippines. At its height, the group had several hundred thousand members.

The initial leader of the Katipunan was Andres Bonifacio. He came from a working-class background with limited education, unlike the elite llustrados who had studied abroad and came from affluent Filipino backgrounds. However, Bonifacio did possess an unique ability to manage, organize and coordinate a vibrant revolutionary movement.

Bonifacio had one major weakness. He was not a good military strategist and tactician. Just because he was a brilliant political and revolutionary organizer did not make him a good military commander. He also refused to delegate military matters to more seasoned and competent military leaders once fighting with Spain erupted. He was responsible for some of the early Katipunan defeats during the Revolution of 1896.

Due to Bonifacio’s weakness on the battlefield, a significant opposition to his leadership developed within the Katipunan. Emilio Aguinaldo, a young and talented military leader from Cavite Province, eventually emerged as the new leader. Andres Bonifacio did not accept the change in leadership. He was convicted of treason and sedition and was executed by the new leadership.

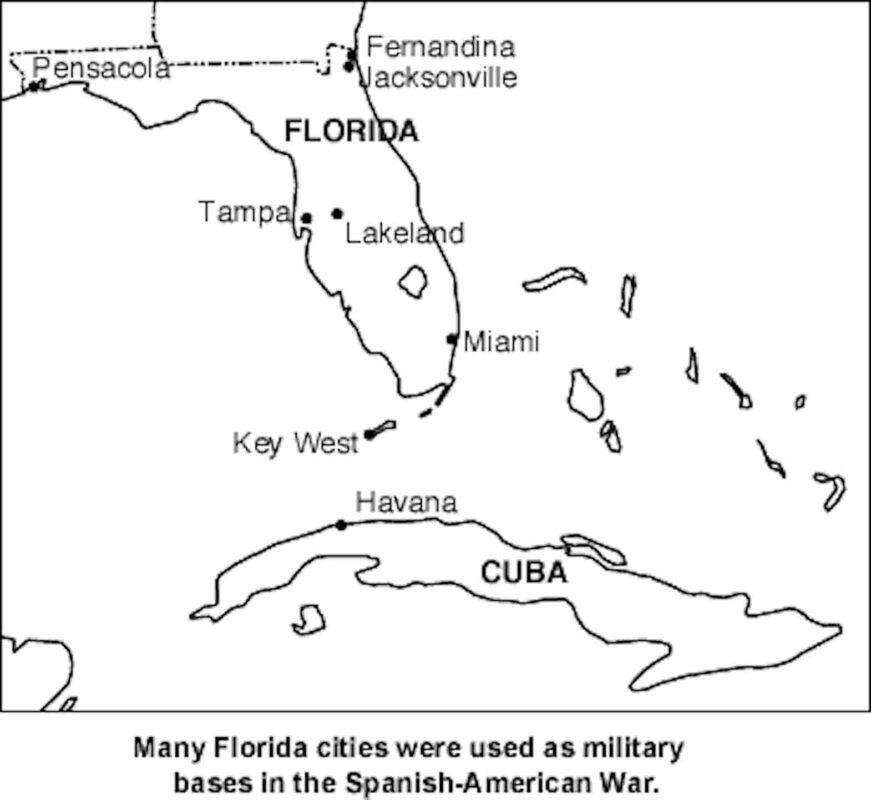

Map shows Cuba’s close proximity to the U.S.

The Revolution of 1896 eventually reached a stalemate by December 1897. The Spanish could not defeat Emilio Aguinaldo and his Katipunan forces. The Filipinos could not overthrow Spanish colonial rule. A pact between the Spanish and the revolutionaries was negotiated. Spain promised some reforms and agreed to a cash payment to theinsurrectos. On the eve of the Spanish-American War, Aguinaldo and his lieutenants were exiled in Hong Kong preparing for a returned to the Philippines.

The Cuban insurrectos on the eve of the Spanish-American War emerged in 1895. The origins of the rebellion dated to the Ten Year War of 1868 to 1878. In 1895, Cuba was experiencing difficult economic problems. The conditions were ripe for a rebellion.

The Cuban insurrectos had several advantages compared to the Philippine insurrectos. Cuba’s proximity to the United States allowed for a Cuban government in exile. Cuban revolutionaries had established communities in Florida, New York and New Jersey. The groups made many speeches in the U.S. on Spanish atrocities in Cuba. The speeches were covered by America’s “yellow” journalists. The speaking events provided a platform to raise money for the rebel cause.

Another advantage that the Cuban rebels had was the logistics of shipping weapons and supplies to Cuba. While it was against U.S. law to ship weapons and supplies to Cuba, and the U.S. and Spanish navies did interdict many vessels carrying contraband, a significant amount of materials did reach the rebels.

An added benefit that the Cuban insurrectos had over the Philippine rebels was the size of American investment in Cuba. Large American companies had substantial business interests in Cuba. A sizable number of American citizens lived in Cuba, especially in Havana. There were “Filibusters” who served with the Cuban rebels. They were not mercenaries, but American men who were idealistic or seekers of adventure. All of this made the United States very intertwined with Cuban government and politics.

One horrific military strategy and tactic that the Spanish utilized in both Cuba and the Philippines was the reconcentration camp or reconcentracion. General “The Butcher” Weyler was the originator of this technique in both Cuba and the Philippines. The policy separated the rebels from the supporting population by forcibly putting the people in concentration camps. Deaths from diseases and starvation were common.

On the eve of the Spanish-American War in April 1898, the Philippine and Cuban insurrectos were poised to finally defeat the Spanish. Based on the backgrounds of both rebel groups, the Cubans certainly had an advantage over the Filipinos during the Spanish-American War and especially throughout the postwar dynamics.

Dennis Edward Flake is the author of three books on Philippine-American history. He is Public Historian and a seasonal park ranger in interpretation for the National Park Service at the Eisenhower National Historic Site in Gettysburg, PA. He can be contacted at: flakedennis@gmail.com