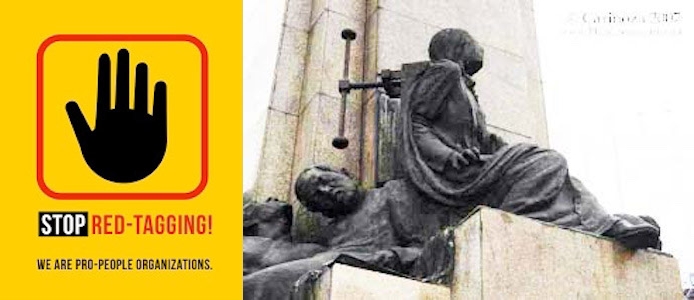

“Red-tagging” is simply a variation on the many pejorative terms used throughout history by the state to mark its enemies, real or imagined.

NEW YORK—Red-tagging may seem like a relatively modern, if ominous and deadly, practice wherein the Philippine state labels as Communist those of its critics seen as particularly troublesome, part of the so-called Red Menace. But the label is simply a variation on the many pejorative terms used throughout history by the state to mark its enemies, real or imagined.

During the late Spanish colonial period, those of the native populace thought to be anti-Spanish and anticlerical were considered filibusteros—meaning “subversives,” the equivalent then of red-tagging—and thus subject to state-sanctioned punishment that often included execution. In 1872, three Filipino secular priests whom the Spanish friars saw as threats to their hegemony were falsely accused of masterminding the revolt that took place on January 20 at the Cavite Arsenal.

The three were Mariano Gomes, parish priest of Bacoor, a town in Cavite; Jose Burgos, canon of the Manila Cathedral, and the most well-known of the trio; and Jacinto Zamora, parish priest assigned to the Cathedral. Gomes at seventy-two years of age, was the oldest of the three. Burgos and Zamora were in their mid-thirties.

The soldiers at the Cavite Arsenal, including those who had retired, and those who belonged to the Marine Infantry—the company from which the Arsenal soldiers were drawn—were normally exempt from paying tribute, really a poll tax, a privilege they had long had. However, on January 20, 1872, much to their dismay and anger, their wages were reduced by the deduction of the tribute, on the orders of the civil administration.

That night, according to the report of the British Consul stationed in Manila, “the troops in the garrison … revolted and took possession of the fortress of that town. The Spaniards residing in the fortress were killed, in all about eleven persons. The mutineers numbered some 250 persons and were composed of native artillery, infantry, marines, and a few of the workmen in the arsenal.”

Like most native uprisings of the past, this one was quickly quelled, and by other native military units, no less, whom the mutineers apparently expected to join them by turning their guns on their Spanish officers. There really had been no previous planning to speak of, no organization, no linking up with other neighboring towns and nearby Manila—just across the bay—and thus was in effect more of a spontaneous revolt.

In short, the Cavite uprising was literally and figuratively a ningas cogon or a flash in the pan. It would have wound up in the dustbin of history, except the Spanish friars saw in the uprising an opportunity to get rid of those pesky secular native priests who had campaigned for reforms in the religious hierarchy that would result in their being assigned more parishes and thus gaining them more power, a scenario anathema to the friars long used to a colony that saw no separation of church and state.

To link the three priests to the mutiny the friars relied principally on the testimony of one Francisco Saldua. In Saldua’s telling, if successful, the revolt would have seen the installation of Burgos as the head of a revolutionary government, the two other priests assisting him. The United States would provide warships to back up the new regime. No solid evidence was otherwise provided for what was quite clearly fanciful, if not fantastical, testimony. And the judicial proceedings were conducted in secret, speedily concluded with the three condemned to die by the garrote, a form of strangulation by tightening a mechanical cord wrapped around the neck until the victim is asphyxiated. The state-sponsored killings were carried out on the morning of February 17, 1872, in Bagumbayan, the same site by Manila Bay where Jose Rizal was executed by firing squad in 1896 and which is now Rizal Park.

Ironically Saldua, the friars’ star and possibly sole witness (I say “possibly” as the proceedings have never been made public), was himself executed that same day, lending weight to the belief that he was a paid informant, an agent provocateur. Allowing him to live would have posed too grave a threat to the friars.

It is said that Burgos, the most erudite, eloquent and fierce critic of the friars’ tyranny and thus their main target, just before he was led to the garrote, shouted that he was innocent. To which a friar responded, “So was Jesus.”

To his credit, though he had been asked to, the Archbishop of Manila refused to defrock the three clerics, an indication that he didn’t think the three were in any way part of a plot to destabilize the colonial government. Besides, he argued that executing three men of the cloth would not sit well with the devout Filipinos.

The martyrdom of the three, collectively referred to as GomBurZa, radicalized the generation of Rizal, who dedicated his second novel El Filibusterismo, to their memory. By executing the three priests, the friars set in motion what they had sought to suppress: the birthing of a national consciousness. On the 151st anniversary of their deaths, it is a lesson the red-taggers should heed. Copyright L.H. Francia 2023