Kearny Street Workshop still full of fire at 45

Journalist Bernice Young, writer Jessica Hagedorn and rapper Ruby Ibarra will lead Kearny Street Workshop’s 45th anniversary celebration. CONTRIBUTED

SAN FRANCISCO – The pioneering and longest-running multidisciplinary arts organization and incubator of Asian Pacific American artists in the nation, Kearny Street Workshop (KSW), is celebrating a milestone anniversary with Building Legacies: 45 Years of Art and Resistance.

The 45th year anniversary celebration kicks off on April 19 with a sold-out event at the Chinese Culture Center, 750 Kearny Street, featuring a dinner prepared by Sita Kuratomi Bhaumik, co-founder of the People’s Kitchen Collective, a conversation between renowned author and playwright Jessica Hagedorn and award-winning journalist Bernice Yeung, and a performance by rapper Ruby Ibarra.

The KSW Ignite Award will be presented during the anniversary festivities to a contemporary artist that reflects KSW’s mission and values.

Artist and former KSW Director, Nancy Hom will unveil her newest mandala celebrating KSW’s 45th year at BAMPFA, 2215 Center St., Berkeley, on March 15 as part of the Kearny Street Workshop: Evolving Legacy exhibition at the museum.

“We are very excited. Folks are gonna be in for a treat,” says writer and KSW Board Vice President Paul Ocampo.

Grassroots movement

Founded by Jim Dong, Lora Foo and Mike Chinn, KSW began as a grassroots activist art movement fueled by a need by APA artists and communities to be heard and recognized in a racialized mainstream society and culture.

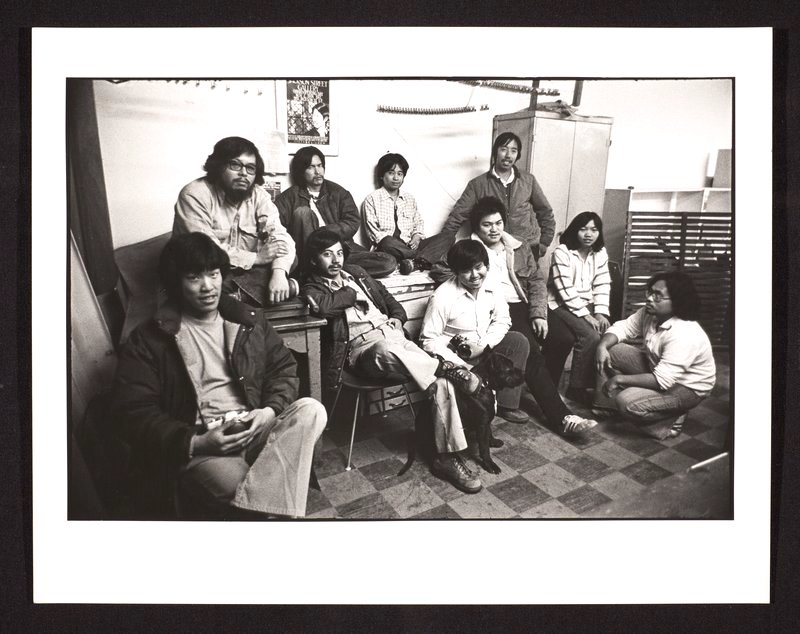

In the old days at Kearny Street Workshop — Leland Wong, Dennis Taniguchi, Jim Dong, Crystal Huie, Jimmy Yee, Terry Chow, Jack Loo, Nancy Hom, and Rich Likong. CONTRIBUTED

Dong and Chinn were students at San Francisco State University (SFSU) during the legendary 1968 student-led strike that led to the establishment of the College of Ethnic studies. Both were student activists and artists who made silkscreen posters for different organizations and events.

“We got together thinking that we needed a place to do the work,” says Dong. “Lora helped putting together the logistics. She rallied the support of other like-minded community people and was more of the organizer of the KSW beginnings.”

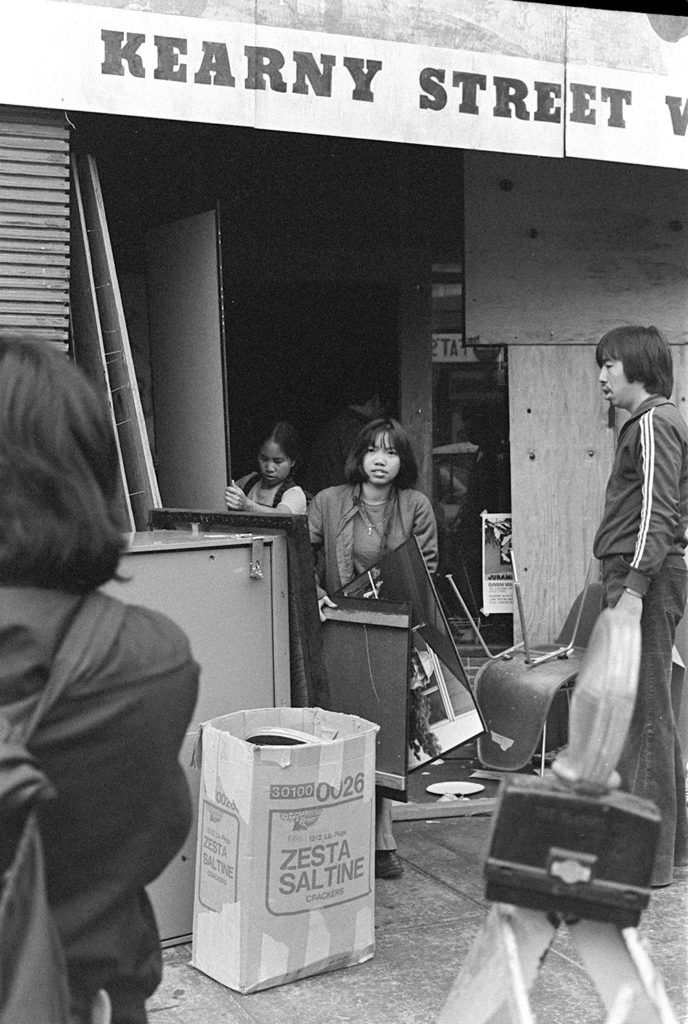

They found space in a storefront at the International Hotel (I-Hotel), home to a large Filipino population and many Asian Americans, on Kearny Street in what was then Manilatown.

Space at I-Hotel

“We shared the space and split the rent with a small export business that sold a mix of old TV’s and sacks of mung beans,” says Dong.

Their workshop gained the attention of members of the community.

“We used half of the facility to do our silkscreen printing,” says Dong. “And it grew to more people coming to help. Lora’s forte was tailoring and sewing and ran early workshop classes. People knew us as Kearny Street Workshop, and it stuck.”

By 1972, what started as a graphics workshop for community use organically grew and branched out into other arts and programs.

“From there the organization began,” says Dong. “Also, people were attracted to it who were not necessarily artists but were involved in social programs in the Chinatown and Manilatown area.”

Their existing arts program included summer activities for disenfranchised youth.

“There were hundreds of kids each week coming through taking classes,” says Dong. “We would also provide events like field trips and camping.”

Around the corner from the I-Hotel was the Jackson Street Gallery where KSW exhibited student works from the workshops and by other artists in the community.

Numerous activities

“We had meetings about the activities—gallery openings, getting exhibits ready, and classes,” says multimedia producer, photographer and KSW alumnus, Richard Likong.

There were year-round workshops in photography with darkroom printing, screen-printing, ceramics, needlepoint, sewing (pattern-making), jewelry, boxing, and many others. KSW became the prototype for community arts centers nationwide.

“The workshop’s success provided the National Endowment for the Art’s 1973 annual report a model for grassroots community arts centers nationally,” says Dong.

Chinn actively stayed for about a year using his background in photography and silkscreen to produce socially conscious work, and Foo became a lawyer and continued her community work through her legal expertise.

“I was the one who stayed to witness and to help create the formation and transitions throughout the first 15 years of KSW,” says Dong. “I was mainly the artistic director/coordinator and also the grants writer.”

Notable writers and poets have been an integral part of KSW. It was at a reading in support of Chile and the Allende administration at the Glide Memorial Church in 1972 that Jessica Hagedorn, then a rising young writer, first met Filipino American writers Serafin Syquia, Al Robles, Oscar Peñaranda, Bayani Mariano, Lou Syquia, and Jocelyn Ignacio.

Family of writers

“They told me about KSW, and I went right over shortly thereafter,” says Hagedorn. “It became this extended network and family of writers who were telling me about ethnic culture and identity and all of the politics that were going on. It was kind of my education.”

There were many upheavals happening locally and nationally. Art and activism flourished in the turbulent shadows of the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal, urban development and gentrification, and with the rise of feminism, gay rights, and the burgeoning counter-culture.

“The Asian American community was very much a part of it,” says Hagedorn. “The Filipino community of artists made me feel not isolated.”

Hagedorn, who was active in the North Beach literary scene with the Beat poets, attended George Leong’s poetry workshop at KSW.

“They were very loose workshops,” says Hagedorn. “You read your poem, we talked about it, had a glass of wine, and we talked about it some more.”

“We didn’t have many role models. Asian American writing was just starting to be recognized at that time,” says writer Lou Syquia. “It brought a lot of us together. We learned each other’s stories, histories, communities.”

Peñaranda, a writer, educator, activist, part-time film actor, and an institution in his own right, taught and wrote the curriculum for the Pilipino Studies Program at the College of Ethnic Studies at SFSU, much of which is still being used to this day.

Collaborations

“A lot of the curriculum was written at KSW,” says Peñaranda.

“KSW was a locus,” says Hagedorn who collaborated with Geraldine Kudaka, Janice Mirikitani, and many African American poets in putting a book together about women poets. “We enlisted the help of KSW. It became a part of your network, artistry, and support.”

Many writers wrote about identity issues as a way of navigating where they fit within society.

“Trying to find your history within a white context, between black and white and all that. And with Filipinos, it was within the Asian context,” says Syquia.

Through KSW, they published their stories as well as stories from members of the community.

“We became the voice for the voiceless,” says Syquia. “Nobody else is going to tell our stories for us; our concerns and the truth of what our lives are about.”

“It was a counter voice that needed to be heard,” says Peñaranda. “We just got sick and tired of all the white voices, and we knew we had better stories to tell.”

“It was a voice for the Asian American community—keep the idea going for future generations of what is Asian American art and culture,” says Likong.

Other artists who helped forge APA art and culture at KSW were Leland Wong and Nancy Hom, writers Nelson Yu, Doug Yamamoto, Russel Leong, Genny Lim, Norman Jayo, Jeff Tagami, and Shirley Ancheta, writer and actor Lane Nishikawa, and photographers Crystal Huie, Leny Limjoco and Tony Remington, to name a few.

History with I-Hotel

KSW history and roots are intertwined with the I-Hotel. After the first eviction notices were issued in 1968, the threat of eventual eviction loomed large despite the extended lease granted in 1969. KSW artists and activists were involved in the resistance.

“That was the experience that galvanized many Asian Americans,” says Syquia.

Kudaka was raising funds to be used in hiring lawyers for the I-Hotel. “We knew something was gonna happen, and they were gonna need all the legal services that they could get but nobody had the money,” says Hagedorn. Kudaka then told Hagedorn, “We could rent some rooms and donate the money.” But the rooms needed work. “We did that,” says Hagedorn. “I vividly remember going there at night to paint the rooms.”

Another round of eviction notices was issued in 1974. In 1977 displacement as a result of encroaching development and gentrification continued and what the community had resisted for a decade came to pass.

“The I-Hotel tenants were evicted and it was demolished, and so was KSW,” says Ocampo

Since the fall of the I-Hotel, KSW has moved around in different spaces around the city. Currently, it rents space in Arc Studios and Gallery on Folsom street.

“In some ways, KSW is not a building; it’s just this tenacity and perspective and love for the arts,” says Ocampo.

Springboard

For 45 years, KSW has served as a springboard for emerging artists.

“As a young writer it was through KSW that I thought I could be an artist,” says Ocampo. “I wouldn’t have found models or folks who have done this before me.”

“One of the things that sustained me was to have spaces where I could be around other artists of color, other Asian American, other Filipino artists,” says poet and KSW Artistic Director, Jason Bayani.

Many opportunities now abound for APA artists for funding and exhibition, but the majority of these opportunities are challenging for emerging artists.

“Sometimes they require a rap sheet of where you’ve been published or where you’ve performed. KSW seems to be that one place just inviting anybody and everybody who wants to be an artist,” says Ocampo.

“We are creating these spaces for the artists in the city outside of the mainstream art world where they can come to and just be,” says Bayani.

Some of the artists that KSW supported through the years have broken through the mainstream: comedian Ali Wong; filmmaker Wayne Wang; musician Vijay Iyer; graphic novelist Gene Yang; comedian Hasan Minhaj; DJ QBert; cartoonist Thi Bui; culture jammer Kristina Wong; and Cartoon Network’s Helen Jo.

Continuing challenges

Despite breakthroughs, many of the issues KSW artists addressed at its birth continue to challenge APA communities today, including the criminalization of immigrants, racism, and harassment and abuse of women. Funding, sustainability, and recognition also ongoing challenges.

“We are a very small organization with only two to three staff members at any given time. It’s a challenge to secure money for programs. It’s a challenge to find space. We’re fortunate that we rent inside a gallery that’s very gracious for allowing us to have space, but I think there’s a difference in being able to have your own,” says Bayani.

“Despite the 45 years, not a lot of people are aware that we exist or are aware of our history,” says Ocampo.

KSW hopes to grow its staff and programming and to get more people involved.

“We can only do this with solid financial support especially from our own community,” says Ocampo. “It would mean so much to the community and the organization if people would just turn out, and that’s the way they can be inspired to give. They need to know the kind of work we’re doing, the kind of programming we have.”

KSW has built great legacies through art and resistance for 45 years, but the struggle continues.

“These are issues that we continue to face,” says Bayani. “It’s not only the legacy of great artists that come here but what those artists are about and what this organization has been about throughout the years.”

“What we need to do is to make people realize that it’s a daily need to keep on thinking critically and to keep on being vigilant,” says Peñaranda.

“I am grateful for Nancy Hom, Zand Gee, Mark Izu and all the KSW members of past decades that picked up the ball when I was ready to drop it in the mid 1980’s,” says Dong. “The strength of the organization was always in its participating members. No matter the location for 45 years, KSW doors were opened to welcome community based artists willing to share, learn, produce, present and/or serve the community through art.”

https://bampfa.org/event/kearny-street-workshop-evolving-legacy