Guerrillas in the Philippines during World War II

Guerrilla units were formed almost immediately when the Japanese invaded the Philippines in December 1941.

Non-conventional warfare was common during World War II. In countries occupied by Axis powers guerrilla movements formed to counter the occupation. Unfortunately, most of the historical focus on guerrilla activity has been on the European Theater. The French Underground and the Yugoslavian Partisans have received extensive coverage and attention.

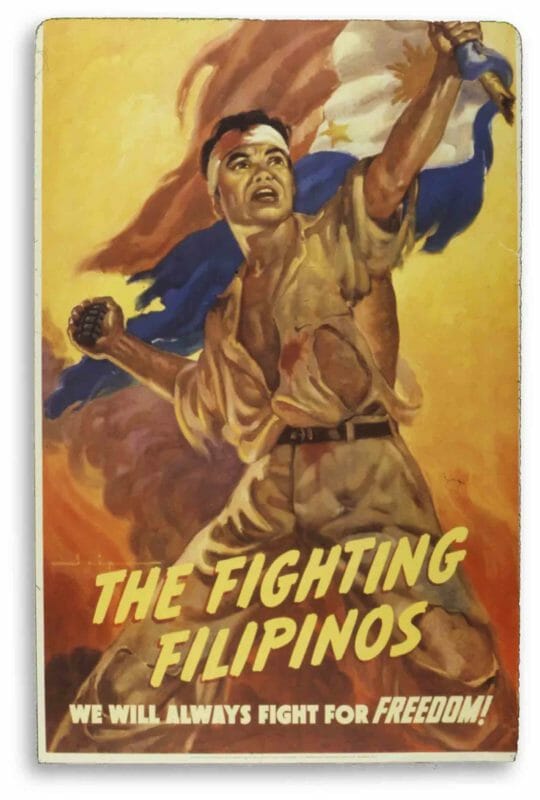

Guerrilla activity in the Pacific Theater has been generally less known than the non-conventional fighting in Europe. The guerrilla movement in the Philippines was enormous, skilled, organized and complicated. The men and women who faithfully served in the guerrilla units throughout the Philippine archipelago deserve exceptional credit for the defeat of the Imperial Japanese war machine in the Pacific Theater. Without the service of the Philippine guerrillas, many more Filipinos and Americans would have died during the war.

Non-conventional warfare has been utilized since time immemorial. When a weaker group was invaded and controlled by a significantly larger and stronger group, guerrilla strategy and tactics made good sense. In the Philippines, guerrilla strategy and tactics had been used against Spanish and American colonialism in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Guerrilla units were formed almost immediately when the Japanese invaded the Philippines in December 1941. General Douglass MacArthur had declared Manila an “open city” after his transfer to Corregidor, but guerrilla units in Manila carried out sabotage of useful military equipment and supplies in the city.

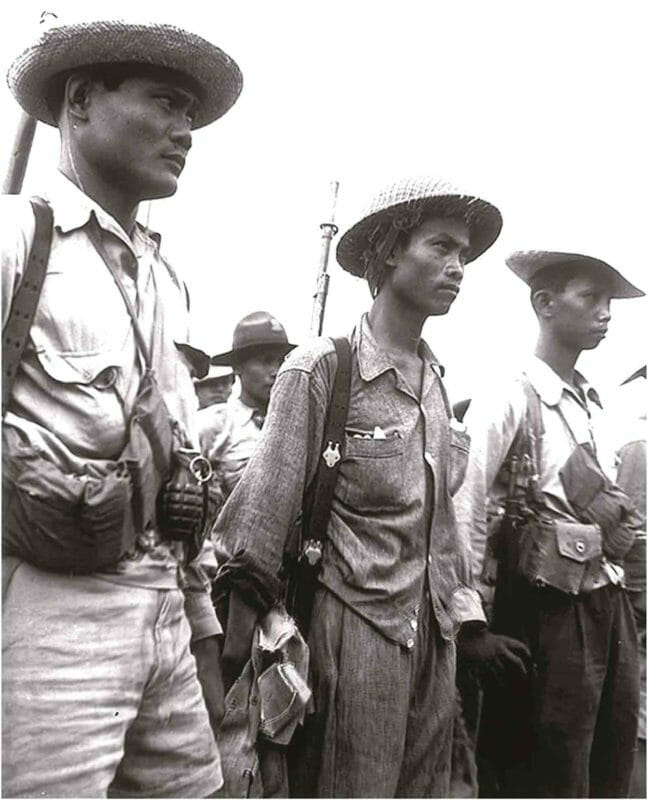

When the fighting in Bataan started looking extremely bleak for the Filipino and American troops, some soldiers decided to run to the hills and mountains instead of becoming prisoners of war. After the surrender of Bataan in early April 1942, the number of guerrillas and units increased dramatically with escaped Filipino and American soldiers. Initially, most of the units were without organization and leaders.

Many of the newly formed units were composed of Filipino leaders and Filipino rank and file. Numerous postwar publications gave the impression that Americans led most of the Philippine guerrilla units. Some of the leaders were Americans, but they were in the minority. Most of the Filipino and American leaders were good, but some were thieves who wanted inflated military ranks. There was also a sizable contingent of Filipino women in the ranks of the guerrillas.

Shortly, there were guerrilla units throughout the Philippines. The units in the southern islands had better equipment and supplies since they had never formally surrendered to the Japanese. They were able to retain their weapons.

In the fertile areas of Central Luzon, there were two types of non-conventional fighters. First, remnants of the United States Armed Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) made up the largest number of guerrillas. Most of the Filipinos had served in the Philippine Commonwealth Army or the Philippine Scouts. Most of the Americans had served in the Philippine Department or the Philippine Scouts. There was some conflict, jealousy and antagonism among different USAFFE units. They generally maintained their loyalty to General MacArthur and his Allied Intelligence Bureau (AIB).

The second type of guerrillas, in Central Luzon, were members of the Hukbo ng Bayan Laban sa Hapon or Hukbalahap for short. In English, it translates to the People’s Army Against the Japanese. The Hukbalahap movement in Central Luzon predated the Japanese occupation. During the 1930s there was a substantial conflict between landlords and tenant farmers in rich agricultural Central Luzon. The traditional landlord and tenant relationship had reached a breaking point. Some in the Hukbalahap leadership were communists, but the rank and file were just trying to make a very basic living. Since the movement dated to the 1930s, the Hukbalahap units only operated in Central Luzon and were better organized initially than the USAFFE units.

There were attempts to integrate and coordinate the two types of guerrilla movements, but the efforts were fruitless. There were to many philosophical differences. The USAFFE wanted only war, whereas the Hukbalahap wanted war and a social-economic revolution.

The AIB wanted the USAFFE guerrillas to collect intelligence and avoid direct fighting with the Japanese. The units were supposed to prepare for the return of American forces. If the guerrillas attacked Japanese patrols and bases, General MacArthur was very concerned about reprisal against innocent Filipino civilians.

The Hukbalahap guerrillas were less passive and more active. They transformed easily from average farm worker in villages and covert soldiers at nighttime. They typically attacked Japanese targets where the chance of reprisals against civilians was low.

On January 8, 1945, General MacArthur ordered the guerrillas to attack all Japanese forces in the Philippines. The guerrillas were transformed from intelligence collectors to guides and fighters. The Hukbakahap also participated in attacking the Japanese. Both types of guerrillas performed valiantly and courageously in the fighting during the last few months of the war.

Towards the end of the war, there was a movement of last-minute guerrillas. The late comers wanted to be on the guerrilla bandwagon for status and compensation. Unfortunately, there were minimal paper records due to the concern of them falling into Japanese hands. Thus, it was hard to prove or disprove service in guerrilla units. However, the vast majority of guerrillas were veterans of dedicated service during the war and had earned their honors and rewards.

Dennis Edward Flake is the author of three books on Philippine-American history. He is Public Historian and a seasonal park ranger in interpretation for the National Park Service at the Eisenhower National Historic Site in Gettysburg, PA. He can be contacted at: flakedennis@gmail.com