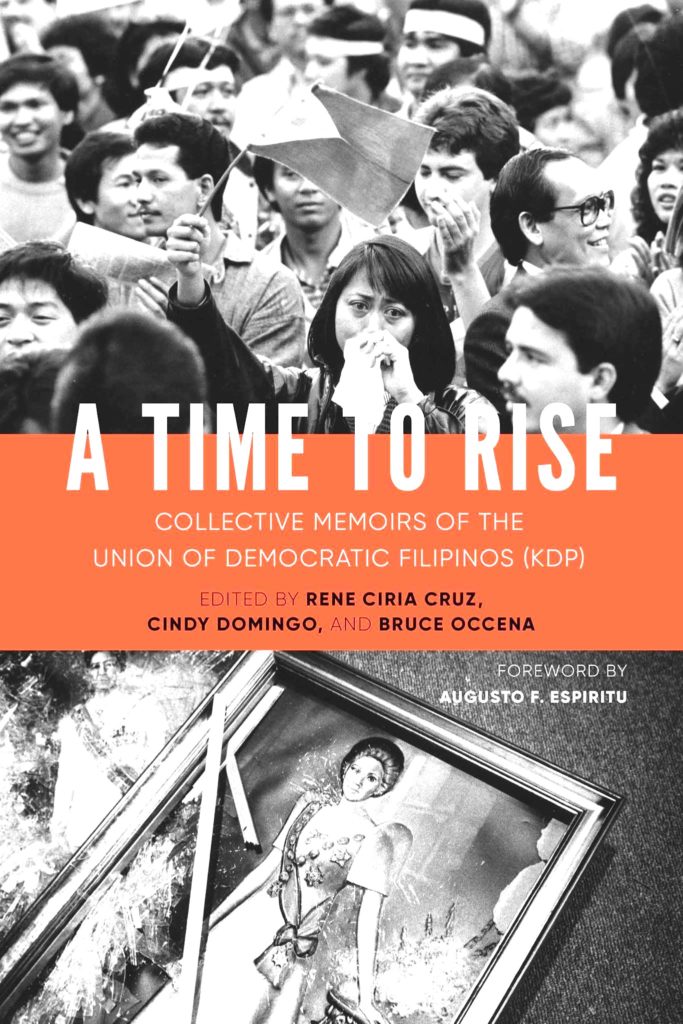

A Time To Rise: Collective Memoirs of the Union of Democratic Filipinos (University of Washington Press)

They were a small band of young Filipino Americans who took on a big cause and faced off with formidable adversaries and critics.

The Marcos dictatorship hounded them. The dictator’s allies in Washington viewed them with suspicion. The traditional anti-Marcos opposition dismissed them as communists. And the communists denounced them as traitors and fake revolutionaries.

At its peak in the early 80s, the KDP — as the Katipunan ng Demokratikong Pilipino or Union of Democratic Filipinos was known — was a vibrant organization of about 300 activists from different backgrounds and based in towns and cities across the United States.

The KDP became arguably one of the most important U.S.-base forces in the fight against the Marcos regime. Many Filipinos and Filipino Americans have probably never heard of the organization, but that could change with the release of a new book.

A Time To Rise: Collective Memoirs of the Union of Democratic Filipinos features more than three dozen personal essays by KDP activists. The book was edited by Inquirer US editor Rene Ciria Cruz, Cindy Domingo and Bruce Occena and published by the University of Washington Press.

The personal essays tell the stories of a diverse group of young Filipinos. Many of them were born and raised in the U.S., the children of Filipino farmworkers and cannery workers, who moved to America in the 40s and 50s.

Others were children of recent middle class immigrants. Some were expats, including Filipinos who were forced to go into exile when Marcos seized power by declaring martial law in 1972.

Many of them had never been to the Philippines and could neither speak nor understand Filipino or any other Philippine languages. But in the 1970s and 1980s, the young women and men of KDP gave pretty much everything they had — time, money, careers, even their lives — to one goal: ending a brutal regime in a country they were determined to help set free.

“The KDP changed my perspective and my life,” Estella Habal, a KDP founding member who grew up in a poor, working class family in Seaside in Monterey County.

“I was always attracted to seeking out my roots as a Filipino because so much of my history was kept secret from me and other Filipino youth,” Habal, now an Asian American studies professor emerita at San Jose State University, writes.

“But sentimentally looking to the Filipino past was not enough. My identity had to also be forged in the direction of the future.”

Like many young Filipino Americans of her generation, Estella sought to forge that identity through activism.

They came of age in the 1960s and early 1970s and were influenced by the movements for civil, women and minority rights, and the opposition to the war in Vietnam. When Marcos declared martial law, Habal and other young Filipinos move quickly to to join the fight against the regime by setting up the KDP.

They would spend the next decade and a half of their lives fighting Marcos.

The KDP emerged as a small, but cohesive organization of activists with “fairly sophisticated operations, with a centralized national leadership and chapters in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Honolulu, Seattle, New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Washington DC, Sacramento, San Diego, and affiliated organizations in Canada,” writes Ciria Cruz.

Activism became a full-time job for KDP cadres who were always prepared to quit their regular jobs, pack up their bags and move to a new city where the movement needed them to serve the cause. They led protest demonstrations and organized forums and house meetings. They lobbied in Washington D.C. playing a critical role in blocking the dictatorship’s bid for an extradition treaty aimed at the regime’s critics and opponents based in the U.S.

The Marcos dictatorship did manage to strike back at the KDP as its influence grew. In 1981, assassins that a federal court later ruled had links to Marcos, murdered KDP activists Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes. They became the first Filipino Americans to honored at the Bantayog ng Mga Bayani.

Traditional opposition politicians were wary of the militant organization which was known to be aligned with the underground left in the Philippines. But that turned out to be a short-lived alliance.

Serious disagreements over the direction of the anti-dictatorship movement in the U.S. led to a break between the KDP and the UG left in the Philippines, led by the CPP. The split was based partly on the KDP view that it was both a movement fighting for the rights of Filipinos in the Philippines and the U.S.

The dispute erupted during one of the major civil rights struggles in San Francisco in the 1970s, the battle for the International Hotel. The I-Hotel was a working class residential building in downtown San Francisco where hundreds of elderly Filipino and Chinese immigrants lived. Most them were poor. When a developer announced a plan to tear down the building, the residents resisted.

It was a fight that the KDP activists were naturally drawn to. But the UG leadership downplayed the importance of the struggle, viewing it as a distraction from more important tasks directly linked to fight back in the Philippines.

Estella Habal recalls how KDP activists involved in the I-Hotel struggle “were criticized for being “maverick and elitist veterans” and leaders who “seemed to have no appreciation for the significance and scope of the I-Hotel struggle.”

The KDP eventually disbanded in 1986 after the fall of the Marcos regime. Many of the activists went on to play key roles in local and state politics. One of them was Velma Veloria who became the first Asian American member of the Washington State House of Representatives. She sponsored the bill that made Washington the first state to criminalize human trafficking. Other activists remained active in their communities or in academe.

A Time To Rise comes out at an opportune time as another fascist regime emerges in the Philippines. As in the past, former KDP activists have responded to the call to fight back.

One of them is Edwin Batongbacal, an immigrant who joined the KDP in 1980. Now a health services professional in San Francisco, he returned to Manila recently to join the September 21 protests. He also has kept busy helping organize talks and house meetings on the Philippine situation under Duterte.

Edwin reflects on his involvement in the closing essay in A Time To Rise.

“Why was I ever drawn into the movement?” he asks in the piece titled “No Regrets.” “Answering this question is important because I now look back at how my life diverged from those of my schoolmates and friends. … I seek some explanation, some reason that would satisfy and assure me that what I did during all my years in the movement was worthwhile, and my life today is all the better for it. …

“I sense that what remains true is to be found not merely in polemics about debatable truths in political philosophy, economy and strategy, but also in the subjective and personal realm of what truly constitutes a life worth living.”

Visit and Like the Kuwento page on Facebook

On Twitter @boyingpimentel