Remembering martial law in Gotham, Part One

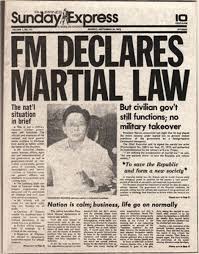

NEW YORK — I had already been living in Manhattan for a couple of years when President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law on September 21, 1972. In truth, he signed the decree on the 23rd, but had it backdated to the 21st because he believed that 7, or any number divisible by 7, was his lucky number.

By then, I had become increasingly aware of the fragile state of our democracy, though not as quickly as my friends and family back in Manila. Whether they chose to or not, they were front-row witnesses to that dark period.

In New York, opposition to martial law was quite diverse, with ad hoc groups springing into existence that normally would have disdained each other’s company but were united only by their desire to supplant the Marcos regime. That fragile unity was bound by the principle that the enemy of my enemy is my friend.

I knew of 1970’s First Quarter Storm from the news, the most intense civic uprising up to that point in the aftermath of World War II, possibly in the whole country, and certainly in Manila. Some years later, I read Jose “Pete” Lacaba’s powerful eyewitness account, Days of Disquiet, Nights of Rage: The First Quarter Storm and Related Events. A friend from our Ateneo de Manila University days, Pete himself was a political prisoner of the regime, and had been tortured by the authorities.

His younger brother was Emmanuel, a poet like Pete, and also a graduate of the Ateneo. We got to be friends as we were habitués of Los Indios Bravos, the bohemian café in Malate run by my late sister-in-law Beatriz Romualdez Francia (though she and my oldest brother Henry, now also deceased, hadn’t as yet tied the knot), and of When It’s a Gray November in Your Soul, another café a few doors down from Indios, owned and run by Ishmael Bernal, who would go on to direct films, such as the classic Himala, with Nora Aunor. A Byronic figure, Eman, as he was known, would go underground in the mid 1970s, joining the New People’s Army, much to the surprise of many of us.

I was at that point naïve politically. The Ateneo that I graduated from in the mid-1960s was immured in ivory-tower innocence, though that was succumbing to the trinity of sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll, the core of our secular theology. Cocooned by privilege, my peers and I were making our way into the world, hopefully without too much angst (a fave word at the Loyola Heights campus then). But two factors rendered that passage—at least, my passage—more attuned to other aspects of life, other than those that had until then been defined by society and by schools.

Those two factors were the Vietnam War, that was being fiercely fought in a Southeast Asian country that the United States had no business being in, and the Plaza Miranda bombing of August 21, 1971, in response to which Marcos suspended the writ of habeas corpus, for a brief period. It was a dry run for martial law the following year.

I learned of a rally to protest Marcos’s action in front of the Philippine Consulate, and joined in. To me it was a lark, and the gravity of what was to come barely visible on the horizon. But it was the start of my political awakening.

The Vietnam War figured in that awakening. This was a war prefigured by the Philippine-American War of 1899, and the resulting occupation of our archipelago meant the intertwining, albeit forcibly, of the interests of the Philippines and the United States, with the latter being the dominant partner. This was a war never studied at the Ateneo of my time, in retrospect a huge gap in our education, certainly in the way that we were taught our history. It was almost as though the Philippines as an independent nation had sprung whole, Athena-like, from the forehead of Zeus America.

On a more humorous note, a friend from Manila was visiting New York sometime in 1971 and had brought along a copy of the by then infamous sex tape secretly recorded by Dovie Beams, a minor U.S. actress hired in 1968 to play the love interest in Maharlika, a biopic of Marcos. Off-screen she and Marcos carried on an affair for two years, with the affair ending in 1970. Beams said she taped their sessions as a form of protection, as she claimed threats had been made against her.

Several of us listened to the tape. We were incredulous but at the same time doubled over with laughter. You could hear the president of the country begging Dovie to perform oral sex. Later on, we could hear their lovemaking reach a crescendo. The tape was a copy of what University of the Philippines students had gotten hold of and played as a loop over loudspeakers on the Diliman campus.

(To be continued)

Copyright L.H. Francia 2017