Class biases in ‘Crazy Rich Asians’ hidden in plain sight

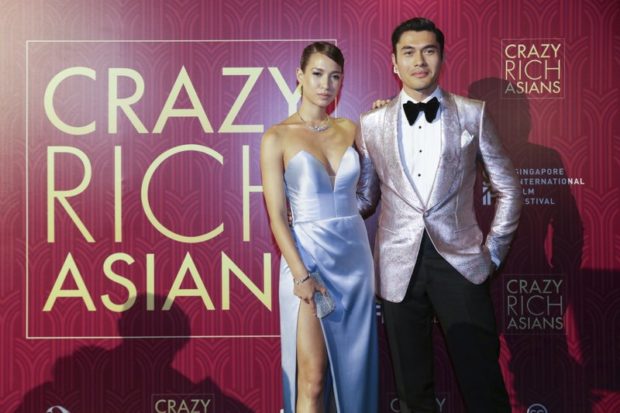

At “Crazy Rich Asians” premiere. AP PHOTO

Last Sunday, I finally went to see Jon M. Chu’s “Crazy Rich Asians,” the romantic comedy from Warner Bros. that has been repeatedly heralded as the first Hollywood film to feature a nearly all-Asian cast in 25 years.

I am not utterly surprised. Thanks to an extensive media hype and a movement on social media its producers created, the movie has had an astonishing worldwide gross at $84 million over its second week at the box office, exceeding industry’s expectations and beating out other movies that have equally good-looking actors but with a long-history and surefire bankability.

Amid the rapturous audiences in a completely packed cinema in New York City’s Lower Manhattan, I couldn’t agree more that it is a well-made, delightfully entertaining movie that takes its viewers to a dreamland, where everydaydresses come straight from couture runways and multimillion-dollar jewelry are much bigger than chicken nuggets.

“Crazy Rich Asians” is indeed racially homogenous. However, while there have been many discussions about how it addresses diversity representation—or how it actually upends the usual stereotypes of Asian characters in Hollywood—what is vastly missing in the debate is how this movie is imbued with caste-like ideological implications.

For most American viewers who, perhaps for lack of exposure to Asian people and their diverse languages and cultures, may not have the ability to distinguish easily who is of Chinese, Filipino, or Malaysian descent based on the person’s accent, body language and facial features, these class biases in the movie are giants hidden in plain sight.

Kris Aquino, a popular and sometimes controversial Filipino celebrity and the youngest daughter of the late Philippine President Corazon Cojuangco Aquino, had a cameo in the movie. To put my argument in context, rather than portraying herself—a Filipino woman from old-money—which would make more sense as the scene depicts the rich and dignitaries coming together for “Singapore’s wedding of the century,” she played the role of Princess Intan, a Malay princess.

But notably, in a couple of interesting scenes, the movie shows maids and servants played by Filipino actors with white aprons wrapped around their bodies, looking ingenuously unrefined and speaking in English with a discernible Filipino accent.

What’s more, the quiet, submissive masseuses at an all-women spa in the movie are Sri Lankans in their native garb, and the security guards of the gated, lavishly grand estate in the film are South Asian Indians wearing red turbans and looking scary like thugs who suddenly appear in the dark.

It tells us, nonetheless, that this movie’s sociological imagination, or the lack thereof, creates a structure for hierarchy of entitlement and vast inequalities that reinforce biases and discrimination among Asian ethnic groups.

I understand that for film director Chu, his personal experience growing up in California and his struggles in a society lacking in politically-correct representation of his cultural heritage had inspired him to make this film. It is in fact admirable, to say the least, that he, along with lead actors Malaysian-born British Henry Golding and American-born Chinese Constance Wu, were prompted to reflect on these systemic biases and address them using a medium that has large mainstream audiences.

The movie’s myopic misrepresentation of social strata in the Asian community also comes too personal for meas a Filipino American. Clearly, I come from a family that isn’t rich, or crazy despite dysfunctions that ordinary families would be expected to have. I don’t have an affluent British accent nor do I linguistically sound American—a few of the Westernized qualities the movie also infers or implies that, paradoxically, one should have to be considered a part of Asia’s upper echelon.

Still, it is not uncommon for me to encounter people—some are Asians—who’d ask, strongly or subtly, if I were a caregiver. With such dignity of labor, I would respond, “I wish I were for I’d be greatly helping America’s aging population.”

But it is not the nature of work, rather the underlying class bias, that I find disrespectful and dangerous. Sadly, I have well-educated friends of Bangladeshi, Filipino, and Sri Lankan descent who have tried to distance themselves from identifying with their ethnic backgrounds because they are concerned about being relegated to the bottom of the Asian social ladder.

Based on the system justification theory, according to New York University psychologist John Jost, “people are motivated to justify and rationalize the way things are, so that existing social, economic and political arrangements tend to be perceived as fair and legitimate.”

In other words, when a certain ethnicity is constantly labeled as, say, maids, servants or low-income, these unfavorable stereotypes or subjugations may be generally accepted by their own group.

If a big hit of a movie like “Crazy Rich Asians” is not sensitive to similar class devaluations among Asian ethnic groups, I am afraid that it existentially perpetuates and legitimizes the notion that economic status determines whether the person deserves equal rights, dignity, and respect. Then, the movie’s ethnic and racial narratives, which have continuously been gaining high-level media tractions, are nothing but marketing tropes.

For what it’s worth, this movie also tells me that it is fine to play up the racial stereotypes and class misrepresentations as long as they work to one’s advantage. While there is hope that “Crazy Rich Asians” will be successful in improving Hollywood views the ethnic background of a leading man or woman, it also articulates a sense of persistent marginalization—and, in this case, among the very people it seeks to elevate.