Forecast shows worsening shortage of mental health professionals in California

A new report forecasts a substantial shortage of qualified and diverse behavioral health professionals in California within 10 years, leaving minority patients and those outside major metropolitan areas especially underserved.

If nothing is done to fill the void by 2028, many people diagnosed with mental health conditions will struggle to get the medication and counseling they need, especially those who live in the Central Valley and Inland Empire, where the lack of qualified workers is worse, the researchers found.

“This affects everybody with a behavioral health condition, particularly those with severe mental illness,” said Janet Coffman, associate professor in policy at University of California-San Francisco and one of the authors of the report, “California’s Current and Future Behavioral Health Workforce.” (The research, released Monday, was funded by the California Health Care Foundation, which also publishes California Healthline.)

Coffman said many people could end up in the emergency room and at primary care clinics, where providers don’t have the same training in treating mental health and substance abuse as psychiatrists, psychologists, therapists and licensed clinical social workers.

Scenarios

The researchers considered two possible scenarios, neither of which looks good.

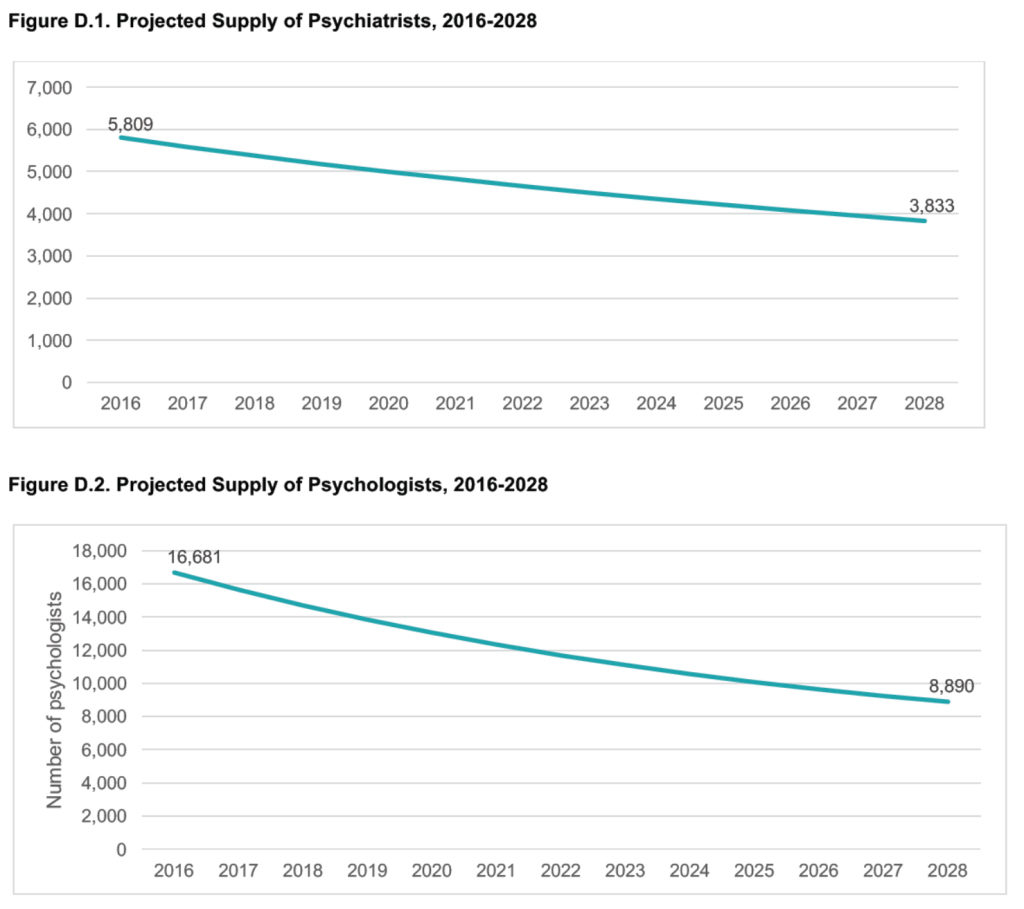

First, they explored an admittedly rosy scenario — projecting what the state would need if current trends in how services are used continue, without figuring in “unmet needs.” In 10 years, they concluded, the state would have 41 percent fewer psychiatrists and 11 percent fewer psychologists, therapists and social workers than would be needed, according to the researchers’ calculations.

The second scenario assumed that the state now does not meet behavioral health needs by a significant margin, based in part on federal estimates. In this case, there would be 50 percent fewer psychiatrists and 28 percent fewer psychologists, therapists and social workers than needed.

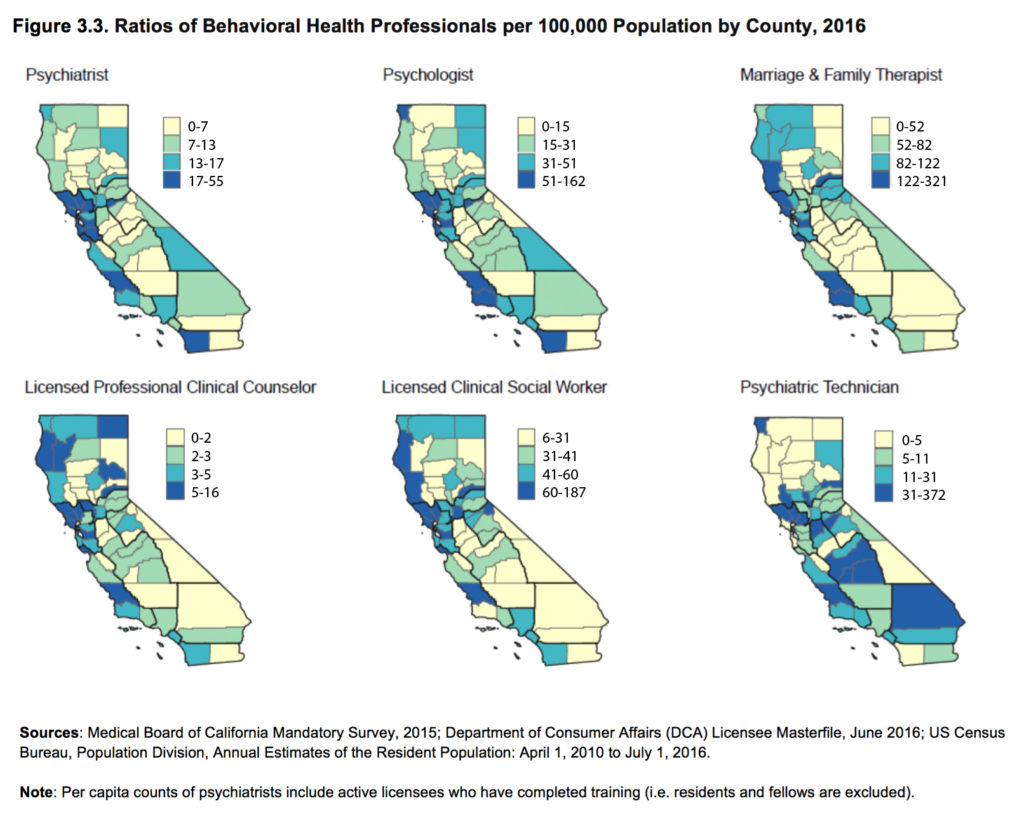

Currently, the San Francisco Bay Area, as well as most metropolitan areas, generally have the most robust behavioral health workforces. Rural areas have the lowest ratios of behavioral health professionals per capita across almost all professions. The region north of Sacramento has no residency programs for psychologists, and the Central Valley has no doctoral programs in psychology. (The study looked only at licensed professionals, not certificated or unlicensed workers.)

Beyond geographical challenges, the research found racial disparities in the behavioral health field, with Latinos and African-Americans underrepresented — only 4 percent of psychiatrists are Latino and 2 percent are African-American, according to the report.

To those who work on the front lines of mental health, the shortages are already here and the time to act is now.

“We have all kinds of issues, with both shortage and diversity of our workforces,” said Dawan Utecht, director of behavior services for Fresno County, while driving to Sacramento to a behavioral health subcommittee meeting on the statewide workforce. “Pretty much any licensed clinical position is hard to fill,” she said. “And psychiatrists, they are in horrible demand everywhere.”

Competing for small pool

As it stands, agencies and organizations are often competing for the same small pool of applicants.

Utecht said her department competes for qualified workers with jails and prisons, which often offer more competitive compensation packages.

In Kern County, the behavioral health department discovered they were losing clinicians, or case managers, to schools that could offer higher pay and more flexible schedules.

Pay is a significant factor. Salaries for behavioral health professions are lower relative to other occupations with similar education and training requirements — meaning they get the same loan debt but less of a payoff.

“These are hard jobs,” said Coffman. “And the salaries don’t look too great.”

In Fresno, Utecht said, it is easier to hire unlicensed workers. They are required to eventually get licensed, but then they are likely to leave for a better-paying job.

“In some ways we are OK with it, because it gives us a ready supply of people, but then they leave,” Utecht said.

Adding to the shortage, the professional workforce is aging. According to the report, 45 percent of psychiatrists and 37 percent of psychologists are older than 60. And many psychiatrists don’t take insurance of any kind, placing their services out of reach for the less affluent. Only 46 percent were seeing any Medi-Cal patients, according to the study

At the same time, the demand for mental health services is great — and growing.

“We’re talking about 1 in 4 people will experience a mental health challenge in their lifetime. That is just huge,” said Zima Creason, president of Mental Health America of California, an advocacy group. There are “just not enough skilled people to do that job or who go into that profession.”

Potential solutions

The report offered potential solutions, as policymakers also pitch proposals:

- Last month, Sen. Jim Beall (D-San Jose) proposed a bill to allow peer health workers who are recovering from mental health or substance use disorder issues to become certified by the state to deliver services to others.

- To increase racial and ethnic diversity in behavioral health, Utecht recommended creating career pathways for minority students and paying stipends for education in the behavioral health field.

- The report proposed that behavioral health services rely more on a team-based model for treatment, where a psychiatrist, for example, acts as an adviser, coach or mentor to a nurse practitioner or primary care doctor, without having to be present for every patient interaction. This would increase access to services while reducing the number of psychiatrists needed.

- In addition, the researchers and other experts recommended that telehealth technology, using video chats for patients to communicate remotely with a professional, be increased throughout the state. “Let’s get with the times, let’s get with technology, and frankly there are some people who would rather be behind a screen than go in and see a person,” Creason said.